Speaking in Singapore last week, former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson lamented growing consensus on Capitol Hill that China is not just a strategic competitor to the United States, but a major long-term adversary. At a time of stark partisanship, the pressing need to reset geopolitical relations with China is an issue Republicans and Democrats can agree on. When it comes to China, rethinking America’s longstanding strategy of engagement has ushered in a wave of openly critical remarks from Washington’s elites.

This negative view of China is not a Trump phenomenon. President Donald Trump is arguably the first to lay out a holistic approach acting on frustration with China, and certainly uses fear of China politically more than his predecessors. But he is able to do so because grumblings in Washington about China’s irresponsible international behavior date to long before the turn of the century. Further, skepticism is not isolated to moderates in each party. A recent bill strengthening investment screening regulations explicitly motivated by China, was co-sponsored in the U.S. Senate by a slew of high-powered, decidedly partisan Republicans and Democrats, including Dianne Feinstein (a Democrat from California) and John Barrasso (a Republican from Wyoming). The John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, strengthening gatekeeping provisions for foreign investment, passed both chambers overwhelmingly before being signed by Trump in August.

What is motivating U.S. skepticism? The answer is partially economic. The past two years have revealed increasing congressional frustration with China’s failure to act consistently with its international commitments, despite reaching a new stage of economic development that positions it to do so. Key to this is the belief that China has leveraged U.S. openness toward goods, capital, technology, and even people to its strategic advantage while not reciprocating back home.

Of course, China’s failure to reciprocate is not a new concern for Washington. But, with China reaching a qualitatively new stage of development as of 2013, U.S. policymakers have begun to perceive lack of reciprocity as less justified than at any other point in China’s 40-year reform and opening period. Engagement, pursued with the unspoken hope of liberalizing China and improving reciprocity over time, has lost political support as a U.S. China strategy. With China flexing its might through large investments in U.S. strategic industries, and flaunting ambitions to swiftly dominate high-tech industries globally, U.S. patience has run dry for China’s insistence that it is a developing economy and deserves implicit concessions when it comes to international rules.

Paulson offers a blueprint to leaders in Washington and Beijing navigating the daunting task of transitioning to a new relationship anchored in a more sustainable and realistic strategic framework. He dismisses fears over existential threats to American civilization, but what is lost in the rest of the speech is a deeper look at roadblocks U.S. policymaker perceptions represent to cooperation. Beyond the friction posed by China’s new development model, a fundamental and historical problem in U.S.-China relations is U.S. policymakers’ inability to accept China’s one-party state as legitimate.

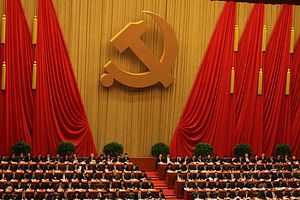

U.S. policymakers view Xi Jinping’s authority to rule as predominantly based on threat of force and severe punishment for dissenters and rivals, which is a source of illegitimacy. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is seen in direct opposition to democratic institutions and as a threat to freedoms of association, assembly, religion, academic thought, speech, and expression. Calls in Congress abound for a China strategy ensuring a “socialist, authoritarian model of government…[never is allowed] to supplant the primacy of democracy.” This means that distrust centers not just on China’s actions, but on the very structure of the government deciding which actions to take.

This skepticism has been brought to the forefront with Xi, who has implied that China is done “biding its time.” Stunning economic growth over the past four decades has made China thirsty for acceptance on the international stage. Acceptance is crucial to proving the form of governance Xi in particular is putting in place – in many ways more anathema to U.S. policymakers than his predecessors’ – is worthy of emulation by others. Xi compounds this thirst by calling for fulfillment of the Chinese dream and national rejuvenation following the century of humiliation China endured starting in the mid-19th century. Experts on China’s “United Front Work” activity, aimed to increase Chinese influence abroad, show that its goals now include convincing Western elites of the Communist Party’s legitimacy and right to rule China.

This shadow of legitimacy is a quiet but key challenge to sustainable cooperation between the United States and China. Economic competition alone is not a sufficient step toward geopolitical rivalry. While U.S.-bound Japanese investment in the 1980s triggered complaints in U.S. policy circles, fear centered on loss of American leadership in key industries rather than critiques of Japanese state aims. Further, the United States has never required its economic partners to fully adopt the norms of neoliberalism. Despite distinct rules and regulations – even involving the role of the state – among capitalist economies such as Japan, the EU, and South Korea, the United States cooperates with each. Even security confrontation between the United States and China could be mitigated, through arms control and confidence building measures.

But ideas are a harder realm of competition to navigate. Ideational competition between the U.S. and China has a long history, but recent economic clashes draw attention to its importance in U.S.-China relations. Deep-rooted perceptions in Washington that the Chinese regime lacks legitimacy and pent-up frustration over that regime’s behavior on the international stage are not a promising mix. These days on Capitol Hill, there is almost zero upside to arguing for more constructive relations with China. That looks unlikely to change in the future, because offenses on each of Paulson’s four fronts — such as technology transfer, IP theft, influence peddling, and trade imbalances — build on this underlying skepticism. Add that to a Chinese regime seeking international legitimacy for its own domestic purposes, and recent trade skirmishes might be a taste of clashes to come.

Lily McElwee is a doctoral student in Contemporary China Studies at the University of Oxford