We are approaching the 100th anniversary of the publication of Sir Halford Mackinder’s Democratic Ideals and Reality (1919). Written as the peacemakers of Versailles were attempting to construct a new world order overseen by a League of Nations, Democratic Ideals and Reality urged the world’s statesmen to adjust their ideals to fundamental geographical realities as demonstrated by history.

Mackinder understood that the Great War was not the first global war in history. “[W]e have had a world war,” he wrote, “about every hundred years for the last four centuries.” Those global wars, he explained, were the “outcome… of the unequal growth of nations,” and that unequal growth was the result of “the uneven distribution of fertility and strategical opportunity upon the face of the globe.”

Asia is considered by most historians to have been a peripheral theater in the Great War, but Russia, a principal belligerent, was both an Asian and an European power. There was much fighting and dying in the Asian lands of the Ottoman Empire, and Japan secured sea lanes in the Western Pacific and Indian Ocean against the German Navy. Japanese forces based in Singapore also helped Britain suppress a mutiny by Indian troops. As a result of the war, Japan took possession of German islands in the Western Pacific and German enclaves on mainland China. Japanese troops also intervened on the side of the Whites during Russia’s civil war.

But at Versailles, all eyes were on Europe. The “Big Four” who crafted the structure of peace were all Western statesmen.

Mackinder in Democratic Ideals and Reality took a broader view than the statesmen at Versailles, and that broader view led him to focus on Asia, not Europe. Just as he had done in his now famous “pivot paper” in 1904, Mackinder reviewed the series of invasions of “mobile hordes” based in the inner recesses of north-central Asia: Huns, Avars, Magyars, and Mongols. “For some recurrent reason,” he wrote, “these… mobile hordes… gathered their whole strength together” and fell “like a devastating avalanche upon the settled agricultural peoples either of China or Europe.”

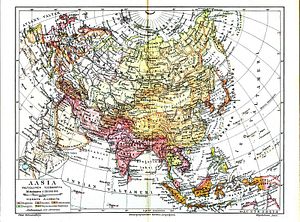

Those mobile hordes, he wrote, were based in a region he called the “Heartland.” He described the Heartland geographically as “a great continuous patch in the north and center of [Asia]… extending from the icy, flat shore of Siberia to the torrid, steep coasts of Baluchistan and Persia.” The Heartland was inaccessible to sea power, and the ubiquity of railroads, motor vehicles, and airplanes constituted “a revolution in the relations of men to the larger geographical realities of the world.”

Europe, Mackinder wrote, was only a peninsula of the great continent of “Euro-Asia.” Asia hosted most of the world’s people and resources. History revealed that the most significant threats to the global balance of power stemmed from an Asian Heartland-based power that conquered parts of Europe (e.g., the Mongol Empire) or a great European power that conquered parts of the Asian Heartland (e.g. Napoleon’s France, Wilhelmine Germany). “What if the Great Continent,” he warned, “were at some future time to become a single and united base of sea power?”

“[M]ust we not still reckon,” he continued, “with the possibility that a large part of the Great Continent might some day be united under a single sway, and that an invincible sea-power might be based upon it?… Ought we not to recognize that that is the great ultimate threat to the world’s liberty so far as strategy is concerned, and to provide against it in our new political system?”

In a remarkable prediction of World War II, Mackinder wrote:

No mere scraps of paper, even though they be the written constitution of a League of Nations, are, under the conditions of to-day, a sufficient guarantee that the Heartland will not again become the center of a world war.

When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, the Heartland indeed became the center of another world war. The victorious power in that struggle for the Heartland — the Soviet Union — became the next empire to threaten to upset the global balance of power. When China allied with Russia in 1950, Mackinder’s nightmare vision of an Asian Heartland-based world empire seemed close to fruition. The great French scholar and strategist Raymond Aron noted at the time that Russia had nearly achieved the geopolitical position “which Mackinder considered the necessary and almost sufficient condition for universal empire.” The American political philosopher and strategist James Burnham viewed Soviet-Chinese control of the Heartland as a sufficient base upon which to bid for world empire. Burnham called for “rolling back” the communist empire because if the communists “succeed in consolidating what they have already conquered, then their complete world victory is certain.”

In hindsight, it becomes more and more evident that the Nixon-Kissinger opening to China was a geopolitical masterstroke, and the Sino-Soviet split was crucial to the West’s victory in the Cold War.

In Democratic Ideals and Reality, Mackinder urged the Western powers to prevent a Heartland-based power from conquering China or India, two countries that had sufficient populations and resources to become great powers. He recognized that China and India, like Western Europe, would give a Heartland-based power access to the sea. In his 1904 “pivot paper,” Mackinder warned that if China with its huge population commanded the Asian Heartland, it would “add ocean frontage to the resources of the great continent,” and thereby threaten to upset the global balance of power.

Today, some observers have sensed echoes of Mackinder in China’s growing navy, its Belt and Road Initiative, and its warming relations with Russia. One hundred years later, Mackinder’s Democratic Ideals and Reality still informs our understanding of the world.

Francis P. Sempa is the author of Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century and America’s Global Role: Essays and Reviews on National Security, Geopolitics and War. His writings appear in The Diplomat, Joint Force Quarterly, the University Bookman and other publications. He is an attorney, an adjunct professor of political science at Wilkes University, and a contributing editor to American Diplomacy.