The year 2018 has witnessed rapid changes in peace efforts in Afghanistan. In early February, President Ashraf Ghani put forward an unconditional peace offer to the Taliban. Over the summer, the Afghan government and Taliban honored their first truce in 17 years of war, albeit only for three days. The U.S. government introduced a special envoy for peace in Afghanistan, tasked with ending the longest war the United States has been involved in its history. Russia organized a conference on Afghan peace in Moscow, where the Afghan High Peace Council members and Taliban representatives met. Finally, in late November in Geneva, Switzerland in a two-day conference on Afghanistan development, Ghani announced a 12 member team that will hold peace talks with the Taliban.

Given the dizzying pace of development, there must be an assumption that there is public demand for peace. According to Zalmay Khalilzad, the U.S. special envoy for peace in Afghanistan, Afghans deserve peace after having been at war for 40 years. However, a survey of Afghan public opinion in 2018 reveals a complex picture of public views regarding peace efforts. The results would suggest it’s better not to rush peace efforts.

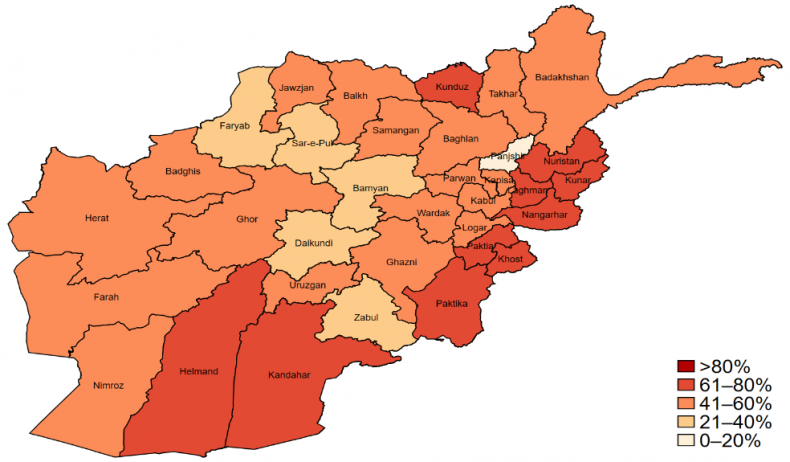

The findings from latest Survey of the Afghan People by the Asia Foundation indicates that some 41.9 percent of Afghans think peace with the Taliban is impossible. Looking at the survey data, it shows that the nation’s view is divided on peace efforts. By ethnicity, the differences are significant: some 63.7 percent of Pashtuns reported that peace is possible compared to just 50.8 percent of Tajiks, 42.5 percent of Hazaras, and only 38.8 percent of Uzbeks (the Taliban are heavily dominated by Pashtuns). The views of men and women also differs, as males (60.5 percent) are significantly more likely to believe that peace with the Taliban is possible compared to women (46.5 percent). Significant differences emerge by regions as well, ranging from 73.6 percent of respondents in the east who opine that peace is possible to only 32.9 percent of respondents in the central/Hazarajat region.

Percent of respondents by province who say peace with the Taliban is “possible.” Data from the 2018 Survey of the Afghan People.

In addition, the survey findings show that many Afghans remain fearful of the Taliban. Some 93.6 percent of Afghans said they feel fear when encountering the group, making the Taliban the most-feared group after the Islamic State (94.9 percent). Meanwhile, only 38.6 percent of Afghans reported fear when encountering the Afghan National Army. This hints that integrating the Taliban will be a difficult process.

The lack of consensus on peace efforts and disagreement extends beyond the general public. Recently Ghani, based on Khalilzad’s suggestion, prepared a list of 12 people tapped to handle negotiations with the Taliban. Soon after the announcement, Afghan members of Parliament and political parties expressed suspicion over both the ability of the negotiation team and its inclusiveness. While political parties criticized the team and questioned whether the Taliban would agree to talk with them, a number of Afghan MPs raised questions over the influence of members of the negotiation team. In addition to this disagreement, Afghan political parties criticized Ghani’s general peace roadmap and said they were not included within the new peace plan.

The disagreement and lack of consensus goes beyond the national level as well. All parties involved in Afghan conflict seem to be convinced that military means aren’t the solution – and that for peace efforts to be successful there is need to have consensus at the international level. And yet that consensus is missing, as shown by the recent conference in Moscow. At the very beginning Afghanistan’s government rejected Russia’s invitation to participate in the conference and then sent members of the High Peace Council — but announced they were not official representatives of the Afghan government. The United States also rejected Moscow’s invitation to participate and cast doubt on Russia’s intention to bring peace in Afghanistan (later, Washington did send a U.S. diplomat to attend the conference).

Experts discuss the fear of a “new Great Game” in Afghanistan and the country becoming a battlefield for regional and international powers. In April 2018 U.S. officials accused Russia of destabilizing Afghanistan by arming the Taliban and supplying weapons to the group. It is believed that one of the reasons for Russia’s move is frustration with U.S. long presence in Afghanistan. Another regional power, Iran, also stands accused of throwing fuel on the fire. Late in April 2018, while the fight between the Taliban and Afghan government intensified in the western province of Farah, the Afghan government complained that Iran was supplying weapons to the Taliban fighters there. The U.S. government too, has accused Iran of providing “military training, financing and weapons to the Taliban.”

It even appears that the Afghan government and U.S. special envoy for peace in Afghanistan don’t agree on a roadmap for peace. Although reports indicate that Khalilzad has been given six months for Afghan peace efforts, Ghani’s speech at a recent conference in Geneva says the peace plan needs at least five years.

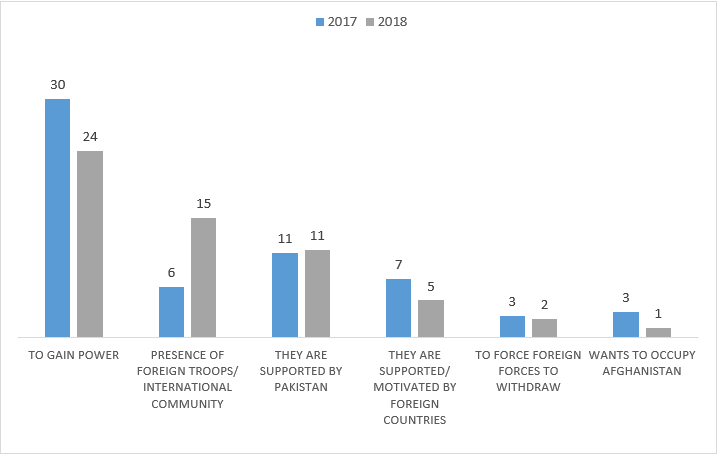

Against this backdrop, the survey findings for 2018 reveal a rise in the number of Afghans who opine that the Taliban are fighting because of foreign troop’s presence (15.2 percent). That’s up from just 6.4 percent last year. Meanwhile, some 11.1 percent of respondents said the Taliban are fighting because they are supported by Pakistan (roughly the same as last year), and 4.7 percent believe they are supported by unnamed foreign countries (a slight drop from 2017). The top reason cited for the ongoing conflict, however, remains the same: that the Taliban simply want to gain power.

Perceived reasons why the Taliban are fighting among respondents. Data from the 2018 Survey of the Afghan People.

Meanwhile, the Taliban’s statement in an interview at a recent conference on Afghanistan peace efforts shows that the group’s view is unchanged from years ago. The group’s ideology does not acknowledge the gains Afghans have made since 2001 in terms of women rights, freedom of speech, elections, and the new constitution. This maybe the one of the reasons while the vast majority of Afghans (93.6 percent) in a survey expressed fear when encountering the group.

Soon after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, the Bonn conference was held to make the new Afghan government. Many Afghanistan experts believe that those talks were overly hasty; one mistake was excluding the Taliban from the conference. Rushed peace talks that exclude or limit public participation have a high chance of failure – just like the Bonn conference on Afghanistan.

To craft a peace settlement that will endure and sustain for the long term, it will take participation by all stakeholders, both national and international. There is no sense in rushing forward.

Mohammad Shoaib Haidary is a researcher with the Asia Foundation Afghanistan and a contributing survey author for the Foundation’s annual survey of the Afghan people.