While U.S.-China relations dominated attention at the recent G-20 Summit, a little-noticed aspect was that Indonesia President Joko Widodo did not even bother to attend. Vice President Jusuf Kalla represented him instead. Widodo was the only head of state among the 20 to skip the meeting, but he offered no explanation for his decision – nor did any Indonesian politicians or commentators question the choice. The official presidential campaign that is underway provides an excuse, but election day is still four months away. Widodo has a massive lead and cavorting with world leaders could have provided advantageous photo opportunities.

In Indonesia, ambivalence about engaging in the international arena is even more pronounced than usual, and this may explain Widodo’s absence. The president has often appeared indifferent about foreign affairs, but now this attitude increasingly applies to cabinet-level policymaking and the broader political arena.

Ironically, with the trade war prompting manufacturers to shift production bases elsewhere in Asia, a prime opportunity now exists for Indonesia to attract sorely needed investment. But, in fact, the giant of Southeast Asia ranks well down the list of desirable destinations for capital in the region: as a proportion of GDP, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was larger in 2016-17 in Vietnam, the Philippines, Thailand and Malaysia. FDI inflows have declined for two successive quarters, according to the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM), and they appear likely to fall again in the fourth quarter.

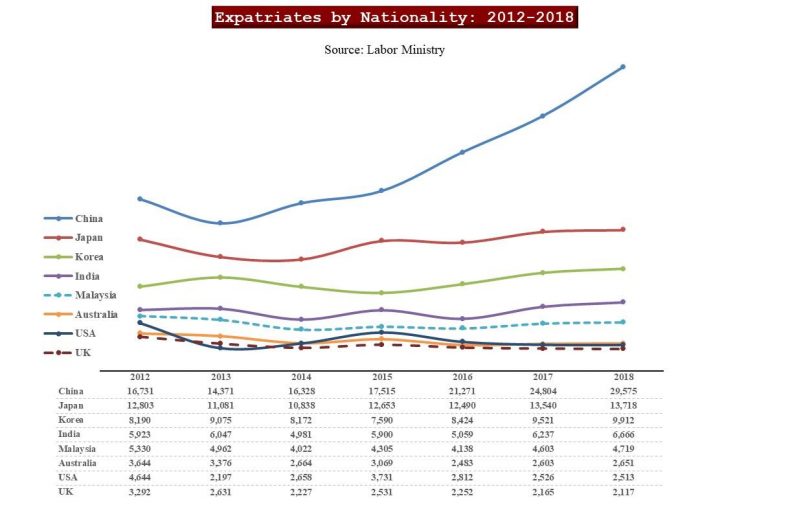

Labor Ministry data shows that work permits for expatriates from key investor nations – Japan, Korea, the United States, the U.K. and Australia – declined by 5 percent from 2012-18. This bodes ill for attracting the capital inflows that Indonesia increasingly needs to fund its current account deficit. With mediocre export performance and heavy dependence on imports (especially for fuel), FDI is essential for preventing yet more currency depreciation in the years ahead.

Nonetheless, foreigners continue to face difficulties in obtaining work permits. The process remains convoluted, expensive, overly rigid and unpredictable. The president ordered investor-friendly reforms in March 2018, but policymakers produced changes that have proven largely inconsequential. (Ministry data shows soaring numbers of work permits for Chinese nationals, but this increase is not commensurate with increased investment flows from China and there is reason to question the value added by the staffing practices of Chinese projects.)

Furthermore, with the adoption of the Automatic Exchange of Information (AEOI), Indonesia’s residency-based system of global taxation serves, in practice, to make the country a highly uncompetitive place for expatriates to work, relative to regional neighbors that are competing for capital. Policymakers are aware of the problem, but Finance Minister Sri Mulyani Indrawati has made no initiative to address it.

Institutional reforms for better governance could go a long way to improving legal certainty, lowering operating risks and improving investor sentiment. But Widodo has shown scant interest in fundamental governance reform. To fill a recent vacancy in a cabinet post that is crucial for bureaucratic performance, Widodo chose a career police general (Syafruddin) with personal ties to Kalla – hardly a choice that inspires confidence for addressing persistent dysfunctions in the state apparatus.

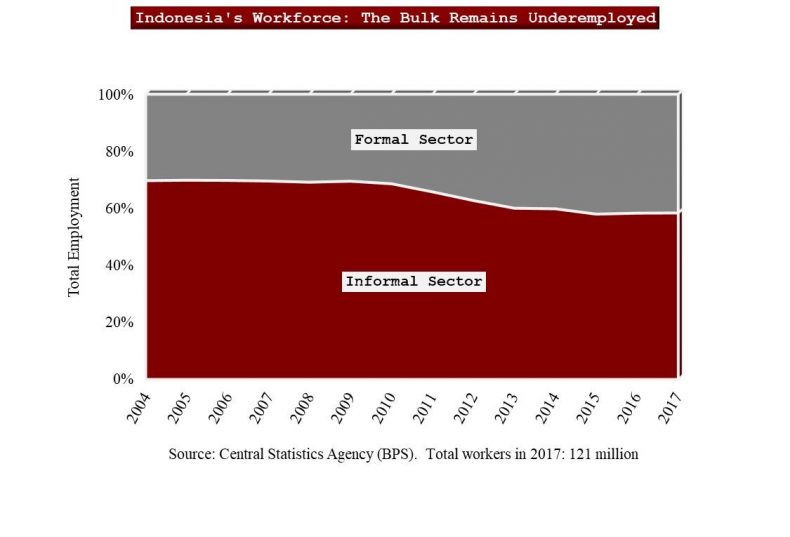

Meanwhile, a host of policies continue to mitigate against foreign investment. Overly rigid labor regulations prioritize iron-clad job security for unionized workers, who number no more than 10 million from a workforce of approximately 120 million. In practice, strictures on hiring and firing workers deters new investment that might create good jobs for the majority of workers (58 percent as of 2017, according to Labor Ministry data) who still toil in the informal sector, with no benefits or safeguards whatsoever. The pernicious pro-union bias of the regulatory framework has been evident since the Labor Law’s passage in 2003, but successive administrations have been too fearful of union demonstrations to broach reform.

In the resource sector, the complacency of policymaking is particularly stark. Foreign mining companies must divest majority ownership within 10 years of commencing operations, while also bundling mines with expensive and highly-polluting smelters – conditions that run directly counter to commercial viability. Widodo’s move to nationalize PT Freeport Indonesia (the world’s largest gold mine and second-largest copper mine) exacerbates the investment climate, especially considering that the state-owned purchaser, PT Inalum, will struggle to fund its share of the mine’s vital $20 billion capital expansion.

The coal-mining sector has benefited recently from buoyant prices, prompting producers to undertake long-overdue investments in their operations. This has apparently propped up levels of fixed-capital formation in the national accounts, while driving an uptick in bank-credit growth (which reached 13 percent year-on-year in October). But this price-induced trend may prove fleeting.

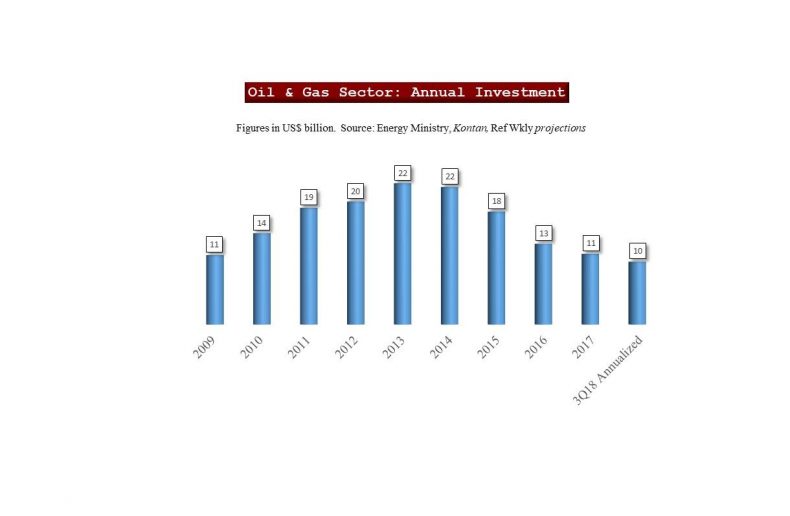

In the oil-and-gas sector, policymakers have repeatedly rejected contract-extension requests by foreign majors, in order to confer production on state-owned Pertamina – despite its weak performance record and inadequate balance sheet. These decisions have exacerbated sentiment that already suffered from an overly cumbersome and inconsistent regulatory framework. Energy Ministry data through the third quarter of this year suggest that upstream oil-and-gas investment is on pace to decline for the fifth consecutive year.

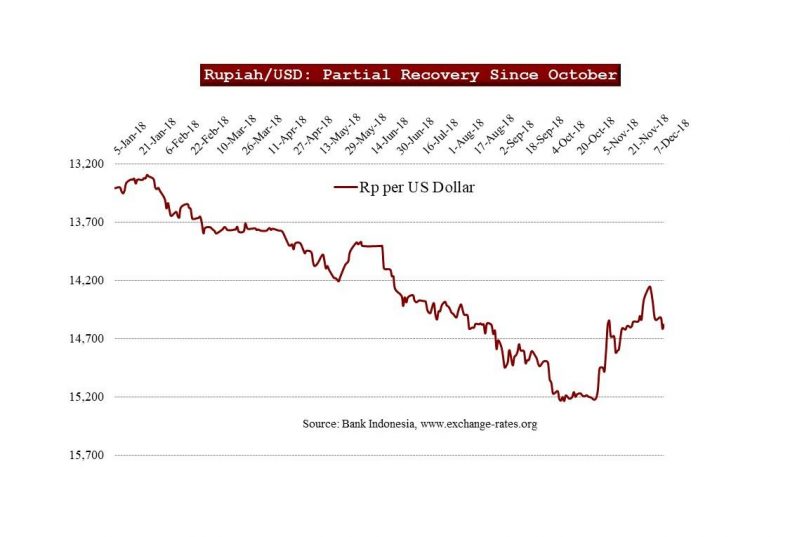

With GDP growth stuck on a plateau of 5 percent per annum, and with a large current account deficit having weakened the currency, reforms to address business conditions in key sectors would presumably be in order. Instead, the latest phase of Widodo’s “Economic Policy Package” (previewed in early November and still only partially implemented) is another damp squib.

A key feature is an attempt by Indrawati to boost “pioneer industries,” such as tech and heavy industry, by offering income-tax holidays that range up to 100 percent for 20 years. Arguably, this is overly generous. Common-sense reforms for governance and institutions could achieve the same result by lowering country risk, without sacrificing future government revenues. In effect, Indrawati’s policy exemplifies how the administration neglects meaningful reform and relies instead on (costly) palliatives.

The other main feature of the package pertains to the so-called Negative Investment List (DNI), which imposes foreign-ownership ceilings on varied sectors. A long-awaited revision has faced delays, and in any event the proposed changes disclosed by ministers constitute little more than tweaks. In particular, there is no meaningful discussion about opening Indonesia’s decrepit education system to increased foreign involvement – a change that is needed in order to better equip Indonesia’s youth to function in a competitive economy.

To be sure, Indonesia’s economy has certain highlights: tourism and e-commerce are robust, while infrastructure development is making real progress. However, state entities dominate the latter and funding constraints loom.

Perhaps the most constructive policy in recent months emanated from the independent central bank: Bank Indonesia (BI) removed debilitating prohibitions on hedging local currency risk. (In the past, skeptics had denounced derivatives as a form of malicious speculation.) BI’s introduction of a relatively easy-to-use hedging instrument (the domestic non-deliverable forward, or “DNDF”) helps reduce short-term demand for dollars, and this has coincided with a period of improved rupiah stability. However, monetary instruments alone cannot steer Indonesia’s economic course.

Widodo’s ambivalence applies not just to international engagement and economic policymaking, but also to democratic pluralism. While strident Islamic groups are making shows of strength, Widodo – along with the bulk of the political elite – remain irresolute. In effect, Widodo is applying appeasement: early last year, he sat idly by while police charged Indonesia’s most effective reformer, Jakarta Governor Basuki Purnama (known as Ahok), with blasphemy (he is still in jail). This year, Widodo recruited a staunchly conservative cleric – a chief accuser of Ahok– as his vice-presidential running mate. The president has extended no support to Grace Natalie, chair of the small pro-Widodo Solidarity Party (PSI), who faced police questioning for having declared that her party opposes “Syariah by-laws” (regional-government decrees that enforce religious behavior). Meanwhile, Widodo’s presidential-election opponent, Gerindra Party Chair Prabowo Subianto, actively courts sectarian clerics, such as the fugitive leader of the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), Rizieq Shihab. The FPI and like-minded groups managed to mobilize approximately one million supporters who descended on Central Jakarta on December 2 – a dramatic show of force that has elevated FPI’s status and leverage.

Some may attribute Widodo’s stances to electioneering, and argue that he will embark on reforms after winning a likely second term. But this view overlooks the pattern of Widodo’s appointments for strategic posts in recent months: The president has persistently favored candidates linked to conventional (or discredited) political elites – including elites whose support is clearly immaterial with regard to re-nomination or re-election. His tendency to avoid reform, appease fringe groups and align with elites has been growing gradually more pronounced over the past two years. The once-enterprising regional head now rarely shows signs of political courage, creativity or inspiration. Rather than an election tactic, this appears to be an intrinsic transformation of his character. Rather than improved policymaking, a second Widodo administration seems likely to offer yet more dithering – which Indonesia can ill afford.

Unfortunately, Indonesia’s demographic dividend is expiring and a middle-income trap is rapidly approaching. Widodo seems likely to coast to re-election, and he can at least offer stability, but another five years of erratic policymaking will be costly in terms of opportunities squandered.

Kevin O’Rourke has been author of the Reformasi Weekly Service on Indonesian Politics and Policymaking since 2003.