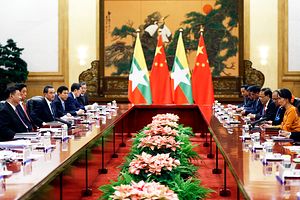

In late November, Ning Jizhe, deputy head of China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), visited Myanmar and met with State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi and the minister of planning and finance along with other ministers. A week later, on December 6, the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) implementation steering committee, led by Aung San Suu Kyi, met. Years after the launch of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Myanmar is finally moving rapidly to embrace President Xi Jinping’s project.

CMEC is a bold step. It will bring China and Myanmar into the closet proximity ever in the history of their relationship, going far beyond trade and infrastructure development itself. This could the ace in the hole for Naypyidaw to overcome deadlocks in the country’s peace process and stimulate foreign investments.

To move from rhetoric to the realization of the corridor, keeping the China-Myanmar border region quiet and stable is imperative. Beijing had initiated and arranged a series of negotiations between the Northern Alliance – groups not represented in Myanmar’s national ceasefire — and representatives from Naypyidaw. Though clashes are still recorded on the ground daily, analysts are expecting a positive breakthrough in the upcoming months. The visit to Myanmar by Yunnan province’s Communist Party secretary, Chen Hao, this week, and his meetings with Aung San Suu Kyi on December 3 and the Myanmar Peace Commission on December 5 can be considered as the dawning of hope to end the conflict along the Myanmar-China border. While the peace process faces turbulence, reaching a positive agreement with the Northern Alliance is crucial for Naypyidaw to uphold confidence in peace talks.

Thousands of kilometers away from China-Myanmar border, at the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) delta, CMEC is already taking shape. Pathein Industrial City, described as part of CMEC project has already signed a deal the China Textile City Network to build garment factories in Pathein; this was reported as one of the largest foreign direct investments in the Ayeyarwady delta area in decades. Meanwhile Naypyidaw has given a green light to survey the Kyaukpyu-Kumming high-speed railway. A package loan from China to upgrade the railway carriages can be considered as one of the first development project of CMEC. Although New Yangon City is still under debate, the contract for the Yangon elevated highway is to be decided in the coming months. Among the 10 shortlisted contractors, six are Chinese companies; it’s highly likely that this project will also be financed as part of CMEC.

Speaking of financing, that remains a major question for the CMEC. The recent approval of lending by foreign banks may pose a possible a solution; however, the changes will not be implemented immediately. Myanmar may have to rely on Chinese financing at least in the initial stages.

Given Myanmar’s worsening relationship with the West due to the crisis in Rakhine state as well as the need for high investments to keep the economy afloat, CMEC is very attractive for the government in Naypyidaw. Whether Myanmar will sink or swim with the Belt and Road will depend on the capacity of the new implementation committee to balance while riding the wave.

Amara Thiha is the Senior Research Manager at Myanmar Institute for Peace and Security (MIPS) and a nonresident fellow at the Stimson Center. The views and opinions expressed here do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of MIPS and Stimson Center.