On the main road leading to the Balochistan provincial assembly in Quetta, a large billboard sports a poster reading: “A walk for Mehrgarh Civilization: From Hanna Lake To Quetta City.” On December 9, activists walked around 16 kilometers from the lake to the city. Many more joined them before their entrance to Quetta. They had one demand, visible on the posters they were carrying and chanted in slow slogans: “Save the Mehrgarh civilization.”

The activists were referring to what is known as the Mehrgarh civilization or culture, named after the archaeological site of the same name. The site itself is a vast area of about 300 hectares covered with archaeological remains left by a continuous sequence of occupations from the eighth to the third millennia BCE.

The site, named after the nearby Mehrgarh village, is located in the Bolan Basin, in the northwestern part of the Kachi-Bolan district of Balochistan. The journey to the Mehrgarh archaeological site takes about three-and-a-half hours from the provincial capital, Quetta, passing through the majestic mountains of Bolan pass.

The Bolan River. Photo by Zulqarnain Haider Mengal.

UNESCO has listed the Mehrgarh site in its tentative heritage list, but it has not been declared a World Heritage Site. Ayub Baloch, an author and former secretary at the Culture, Tourism, and Archives Department in Balochistan, said that Islamabad never took the ancient cultural site seriously. The concerned authorities in Islamabad failed to present the Mehrgarh case to UNESCO in an effective way. Otherwise, he is confident that it would have been declared a permanent World Heritage Site on UNESCO’s list.

In native Balochi, “mehr” means love and “garh” refers to heaven — thus Mehrgarh could be translated into English as “a heaven of love.” But the site in reality tells a different story, one of negligence and looting.

The reality at Mehrgarh is far from what one would imagine for a site of such historical importance. Even in the nearby village, many locals did not know about the site. After talking to several people who had no useful information, local Qamar Ud Din Jatoi finally knew what we were looking for.

The Mehrgarh site is a bleak picture, with potsherds scattered on the ground. There was no sign board identifying the ancient site. Locals say that the site was bulldozed during a tribal feud.

Scattered potsherds on the Mehrgarh site. Photo by Zulqarnain Haider Mengal

“We call this site dhamb, in native Balochi,” said Jatoi. “Dhamb” refers to ancient towns or places that were buried over time.

The discovery of this site is an interesting story.

When French archaeologist Jean-Francois Jarrige and his team were doing excavation on a post-Harrapan site, in Pirak, in the Sibi district of Balochistan, the team was told by some locals from a nearby town that some artifacts had been unearthed after the rain. This new site was actually another dhamb, what would later be known as the ancient settlement of Mehrgarh.

Jarrige along with his team visited that dhamb. “When the mission reached there, they were shocked to see it,” said Professor Jahanzaib Rind, an expert on the subject. “That was the moment when they left Sibi and started excavations in the town.”

The site was excavated by a French archaeological mission under Jarrige’s direction from 1974 to 1985. Work resumed in 1996 and ended in 2000. The excavations uncovered artifacts from the eighth millennium to mid-third millennium BCE, without any cultural break – evidence of continuous occupation during that time.

The Importance of Mehrgarh

There are many who refer to the ancient people that inhabited Mehrgarh as a civilization but technically it is labelled the Mehrgarh culture.

A civilization is considered to be the most advanced stage of human social and cultural organization. “There are some [specifics] ingredients of civilization, such as writing, monuments, a political and economic system,” said Rind. “A culture does not have those all above mentioned ingredients, such as a script. A civilization is more complex and advanced than a culture. “

The world’s oldest known civilizations are the Sumerian, Indus, and Egyptian civilizations. But the definition is more slippery than it would appear.

“This definition of civilization comes from the Western world’s parameters. And it is very subjective,” said Ayub Baloch. “It is very hard to accept this much complexity from a site which dates back to the 8th millennium BCE [and not view it as a civilization]. However, even if you go by the definition of the Western world, cultural sites are no less important than civilizations.”

Rind goes further, arguing that there would have been no Indus Valley civilization if there was no Mehrgarh culture. Although the Indus Valley civilization (exemplified by the site of Mohenjo-daro in Pakistan’s Sindh province) was discovered before Mehrgarh was excavated and studied, the culture that lived at Mehrgarh predates the Indus Valley civilization. The Mehrgarh culture is believed to have been the cradle of the Indus civilization.

Jarrige’s study revealed that Mehrgarh is the earliest known farming settlement in South Asia. The excavations made some major contributions; the cultural sequence evident at Mehrgarh provides a fairly clear picture of the process of humans setting down and establishing domestic plants and animals as their major source of survival. That means the transition to food production can be seen as an indigenous event.

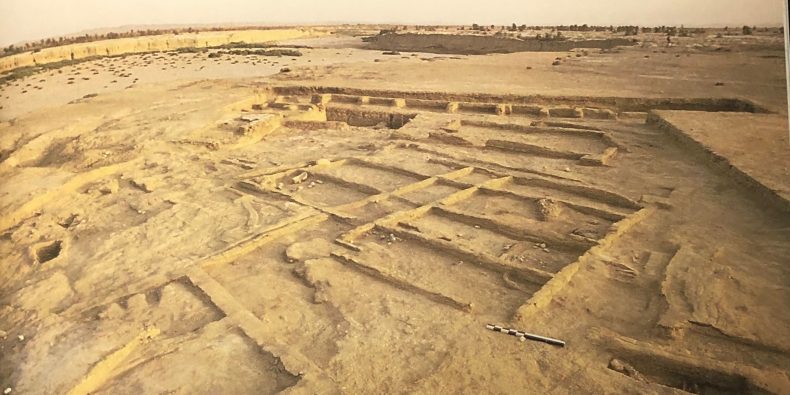

The Mehrgarh site in the 1970s, during excavations by the French archaeological mission. Photo from Jean-Francois Jarrige’s Mehrgarh Reports.

Jarrige carried out 11 seasons of excavations and published them in his Mehrgarh Reports 1974-1985. The report points to several important activities for which Mehrgarh is the earliest known example. First, Mehrgarh is the first known agrarian society, where animals and plants were domesticated, in South Asia. Second, dental surgery (morphology) is also evident through archaeological remains at Mehrgarh – again, making it the earliest site with evidence of such a practice.

The Mehrgarh culture thus played a vital role in the Neolithic revolution.

“One of the major contributions Mehrgarh has provided to the world is to be one of the earliest evidences of an incipient farming economy in South Asia, in a region whose geographical location is of a high significance,” said Imran Shabir, an archaeologist. “The Bolan Basin is situated at the southeastern limit of the distribution area of the wild ancestors of the elements that, later on, were to be predominant among the domesticated species — goats, sheep, cattle, barley, and wheat –exploited in the course of the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods.”

More than that, Mehrgarh was an epicenter for trade and exchanges in the ancient world.

“I don’t believe that trade and communication is a new phenomenon,” said Baloch. “It is a very ancient phenomenon. The evidence and studies prove that Mehrgarh has been one of the world’s oldest trading points.”

The site is located on the principal route between what is now Afghanistan and the Indus Valley.

Rind agrees with Baloch. Jarrige’s research and studies on Mehrgarh prove that there was trade between Mehrgarh and other neighboring regions, he explained.

Rind added, “Exotic materials, such as precious and semi-precious stones and also lapis lazuli, were brought from Afghanistan, processed in Mehrgarh, and then exported to other towns within and outside of region.”

That leads Baloch to declare that the site was home to “factories” of a kind, “if not as equipped and modern as recent factories are. Products were processed in this place and turned into finished products. Mehrgarh has no [access to the] sea but seafoods and shells were processed here. Even buttons were made in the town. They were not very advanced but all the evidences and studies of Jarrige are proof.”

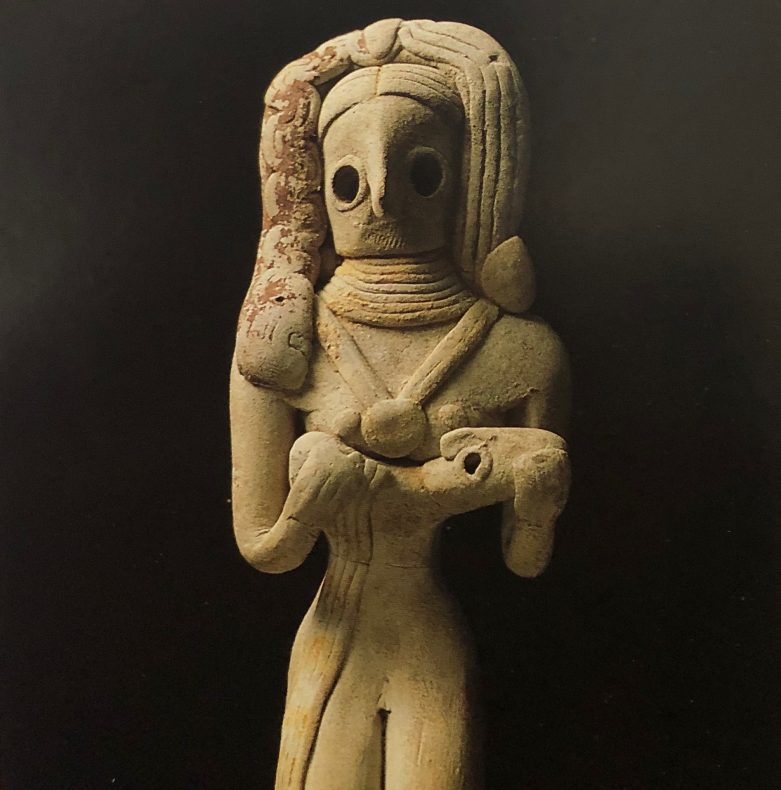

A female terracotta figurine holding a child. This figurine was discovered at the Mehrgarh site. Photo from Jean-Francois Jarrige’s Mehrgarh Reports.

Archaeology can be used for many purposes, including advancing political, economic, social, cultural, and religious narratives. When it comes to Mehrgarh, the archaeological study provided evidence that people have been living in this area since at least 7,000 BCE, but that information only tells part of the story.

“People always rush to the question, what’s their origin?” explained Rind.

“Having the archaeological evidence this question can easily be answered,” he continued. “One thing I have revealed in my research is that migration theory is wrong when it comes to South Asia, particularly Balochistan.”

In his research “Reconstructing the ancient history of the Baloch on archaeological evidence,” Rind argues that the Balochs did not originally migrate to the region, now known as Balochistan, from the outside.

“People who are now living in this region have come from nowhere [else]; they are the habitants. South Asians have not come from Aryans, Alebbo, Arabs, and Persians; rather they have their own identity. They are the son of the soils.”

Stolen Artifacts, Looted Antiquities, and Neglected History

Clearly Balochistan province is very rich when it comes to ancient sites. But there is no university in Balochistan that offers archaeology as a course of study. “Archaeology as a subject is neglected in Pakistan and Balochistan particularly,” said Rind. No locals, whether as participant, researchers or trainers, took part in the French mission during their excavation in Mehrgarh.

In the province there is a dearth of information when it comes to archaeology and ancient sites. Journalists rarely report on these topics and when they do there are often basic errors. A local journalist published a report in the daily Dawn erroneously identifying the ruined houses where Jarrige and his team stayed as the Mehrgarh site itself.

The mud-brick houses where the French archaeological mission lived during their excavations. Photo by Zulqarnain Haider Mengal.

Worst of all, during a feud between the Rind and Raisani tribes, the Mehrgarh site was bulldozed by the Rind. The site was under Raisani control, but the Rind tribe also had claims over it – so they destroyed it.

“He [meaning the then-chief of the Rind tribe] claims to be a tribal chief but he bulldozed the site,” Jarrige’s wife told an archaeologist in Paris. “I might forgive him for disrespecting us but I can never forgive him for ruining the site. He calls himself a tribal chief but knew nothing about this ancient and cultural site.”

Balochistan does not even have a well-established museum to house the large number of antiquities discovered in the province. Around 17,000 archaeological materials from various archaeological sites, such as Mehrgarh, Nausharo, Pirak, Sohr-Dam, Shahi Tump, and Meer-i-Qalat, are kept in Karachi instead.

However, the “Balochistan government is in contact with the Sindh government on bringing back thousands of archaeological objects to the province,” said an official. “The process has already begun.”

In Pakistan, the culture and tourism department – also responsible for archaeological affairs — is considered one of the least valuable departments or ministries. Shabir, the archaeologist, says that the Balochistan government should invest in archaeology by building museums, introducing archaeology as a subject in universities, and appointing archaeologists to the province’s Culture, Tourism, and Archives Department (currently there are none on staff at the department).

But the problems are bigger than bureaucratic hurdles. Antiquities smuggling is rampant in Pakistan. The country is a route for smuggling not only artifacts but many other banned or illegal products. Many antiquity hunters or illegal traders from Afghanistan use Pakistan as a gateway too. In the same way archaeological materials from Mehrgarh have been illegally traded to other continents.

Back in 2014, Italian police recovered antiques from Rome that were stolen from Mehrgarh. The Balochistan government also acknowledged the case. The antiques were said to be thousands of years old and worth of hundreds of thousands of dollars, according to a statement from the Balochistan government.

“It’s not our duty to stop the illegal trading of antiquities. Rather Pakistan customs and other concerned departments should play their roles,” Dr. Fazal Dad Kakar, formerly director general and in charge of exploration at Pakistan’s Department of Archaeology and Museums, told The Diplomat. “We have a big coastline in Balochistan. Most of the antiquities are sent to other countries via the coast of Pasni, Gwadar district.”

But many say that the illegal trade would not be possible without the support of various departments, and that there is a chain of groups and departments in this business.

While walking on the Mehrgarh site, I met a local from the nearby town. He said that when it rains in the village, many antiquities or artifacts come to the surface. Therefore, locals always come to the site after it rains heavily to see what they can find.

“Last year, I found a precious stone and sold it for $50,” said the local, who requested anonymity. “But later I came to know that the local merchant cheated me. The stone was more expensive than the amount he provided.”

A sign marks the entrance to Mehrgarh village. The nearby archaeological site of the same name has no signage. Photo by Zulqarnain Haider Mengal.

Many locals in the town told The Diplomat that they did not even know that selling these artifacts to antiquity hunters is illegal. They think that what they find on the ground belongs to them. They don’t know that what they are selling can be worth so much, or that it is part of the national heritage. The government – both state and local – has failed to even raise awareness of the issue, much less put an end to the business of antiquity smuggling.

“The site needs to be taken care of by the concerned department — the site should be conserved and preserved,” said Shabir.

While walking on the site, it was evident that it has already decayed due to soil erosion and rainfall. The site is rapidly falling victim to vandalism and encroachment both by natural forces and man-made destruction.

As Shabir pointed out, “As per the demand of the discipline, the site post-excavation requires some scientific procedures for further research,” such as backfilling the excavated trenches, conservation of the exposed architectural layout, and other structures preserving the site for the future work.

Ideally, authorities would also undertake the construction of a site museum for storing and exhibiting the regional echoes of the distant past and, more significantly, protective fencing or walls.

Today the site lacks all these amenities and basic scientific safeguards.

“Mehrgah is one of the many ancient sites in Balochistan,” said Rind, “But Mehrgarh has been excavated, studied, and published. Mehrgarh needs to be preserved by making a protective wall on the site, but more important is the conservation, preservation, and study of other sites that are in ruin in Balochistan.”

Shah Meer Baloch is a journalist based in Pakistan. He has had his work published in New York Times, Deutsche Welle, The National, The Diplomat, Daily Dawn, Firstpost, Herald magazine, and Balochistan Times. Zulqarnain Haider Mengal contributed photographs to this report.