This is the fourth and final part of an ongoing series, which traces the origins of India’s people and civilization. Previous parts can be found here: Unraveled: Where Indians Come From, Part 1, Where Indians Come From, Part 2: Dravidians and Aryans, and Where Did Indians Come From, Part 3: What Is Caste?

Indian genetic history is heterogeneous, multifaceted, complex, and unique relative to the population structures of other regions, such as East Asia (characterized by a tendency toward ethnic homogeneity). Due to the times and distances involved, and the highly divergent origins of India’s ancestral peoples, much has been brought to light only because of recent DNA studies, which combined with what is known about India’s social structure and history, now provide a coherent narrative about distinct aspects of India’s ethnography and sociology: caste, religion, language groups, and agricultural practices.

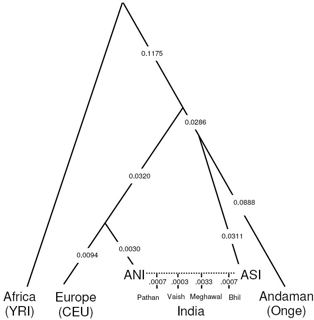

The simplest way to think of Indian populations is as a cline, a continuum with a large number of gradations from one extreme to the other. There is some correlation between language, caste, geography, and genetics, but not a complete one. Generally speaking, higher-caste groups, and people from northwestern India are likelier to have more steppe and Iranian farmer ancestry than lower-caste groups, and people from southern and eastern India. But the geographic correlation is not total, and is relative to each region. Indians are thus not a single “race,” but a mixed population deriving from several ancestral ones. This is more evident among Indians than people from other part of the world where mixing has occurred because the mixing in India occurred between groups with very different physical features, and in different proportions among castes and regions. India’s groups were never fully homogenized to form a new, uniform “race.”

While it is tempting to think of Indian ethnic groups utilizing classical European terminology—as groups sharing a common language and territory—in the Indian context, it makes more sense to think of its thousands of separate castes as individual ethnicities, because they share common descent and customs. The geneticist Razib Khan noted to me that “India is interesting because you have different ethnicities speaking the same language,” whereas in other regions with environmental or social stratification such as Southeast Asia, “language and religion mark distinction.”

The process by which these castes are grouped together in a hierarchy and converge linguistically and religiously is known as Sanskritization, because Sanskritic language culture is associated with the elites: it does not necessarily mean the adoption of Sanskrit by a population; many groups speaking a variety of languages from divergent linguistic families have “Sanskritized,” or become refined, perfected. Sanskritization is a process of social change and cultural assimilation that was particularly prevalent as a form of acculturation in ancient and medieval India whereby groups, particularly new or lower castes in a society emulate the rituals and practices of upper castes, or whereby local elites transform their social structures so as to emulate the classical varna and jati system that was first established in northern India. Sanskritization has been described as similar to the social phenomenon known in the West as passing, in which individuals try to pass off as socially higher than they may be. While Sanskritization of unassimilated tribes and groups occurred mostly in ancient India, the process is still continuing in parts of Nepal and Northeast India that recently came under Hindu influence.

The relatively recent Sanskritization of Manipur, now a state in northeast India bordering Myanmar is an illuminating example of Sanskritization. In the early 18th century, the king of this formerly tribal entity, linguistically and ethnically more similar to the Burmese than to Indo-Aryan and Dravidian Indians, invited preachers from the Vaishnava sect of Hinduism from nearby Bengal to his kingdom. This “brought about a unification of Manipuri social life with the mainstream Hindu society based on caste distinction. The system of…worship of the Vedic deities and Aryan religion rituals entered Manipuri social life as the people embraced Vaishnavism in the leadership of the king.” It is evident that the process of Sanskritization was usually elite-driven:

Sooner or later, power has to be translated into authority, and it was precisely in this situation that Sanskritization was important. He who became chief or king had to become a kshatriya, whatever his origins. In those areas where a bardic caste existed the chief was provided with a genealogy linking him to a well-known kshatriya lineage and even to the sun or the moon. The indispensability of Brahmins is pointedly seen in the fact that in areas where there was no established Brahmin caste the chief had…to import them from outside, offering them gifts of land and other inducements….

Indian culture, as well as some Indian DNA has also entered Southeast Asia as a result of similar, elite-driven processes, as the arrival of traders and Brahmins in places like Cambodia and Indonesia led to the adoption of some aspects of Indian cultures by nobles and chiefs in those areas, though not the formal establishment of a caste system.

How Unique is Indian Society?

Is India just different due to a fluke of history, or does its social structure share similarities with other societies? Writing in A Brief History of the Human Race, historian Michael Cook notes that in India “familiar elements have been put together in a formal system that shapes the society from top to bottom….the rather isolating geography of the subcontinent lends itself to the evolution, spread, and preservation of cultural idiosyncrasies not shared by the rest of Eurasia.” But as Cook argues of the caste system, “none of the underlying ideas is peculiar to India.”

We are used to societies containing a variety of groups that vary in prestige. Such groups may be linked to birth (you can hardly choose to become a Gypsy if you are not one already) and to occupation (a Boston Brahmin does not make a living cleaning toilets). They also make a different to marriage (you are more likely to encourage your daughter to marry a member of a high-ranking rather than a low-ranking group). Though it is impolite, it is not unknown for people in many societies to speak of other groups as dirty. So at this level we could hardly claim that the elements of the Indian caste system are beyond our understanding.

Speaking to me, Razib Khan points out that “it is important to note that caste systems develop everywhere. For example, in the post-Roman era, there was a division between the Saxons and Celtic British. But, they are not strongly religio-ideological. Over time they break down. The weird thing about India is the persistence and deep time depth.” Similar phenomenon did not occur in other civilizations for a variety of reasons. For example, in China, “the Han had an assimilative ideology. Not just integrative [as was the case in India and its castes]. This is explicit in old Confucian sayings. Barbarians can become civilized.” India’s integrative ideology is highly primed for the preservation of caste distinctions, local gods and manifestations of deities, and heterogeneity in general.

On the other hand, intermixing between castes in India has parallels in other parts of the world, especially in areas where extremely distinct groups quickly came into contact. According to Khan, admixture in India between castes “was 1 percent or less for 1,500 years…basically Jim Crow levels of cultural separation.” Similar to the one-drop rule adopted by many states in the American south, anyone with admixture between upper and lower castes was generally assigned to the lower castes to prevent the mixture of lower caste genetic material into the higher castes.

Similar phenomenon can be observed in Latin America, particularly countries like Mexico that large populations of mixed Native Americans and Europeans (mestizos): there is a similar gradation in Mexico, with social status and proportion of European ancestry relative to native ancestry being correlated. Yet, as Khan points out, Mexico could not fully become India because of the shorter time scales involved and because there is no ideological justification for such watertight castes there: “everyone [was] Catholic.” It does not take long for a population to homogenize: in the United States, the “current rate of [racial] intermarriage is now 10 percent (more if you count unmarried couples) per generation. Within 300 years, that will eliminate difference.” For there to be so much difference between Indian castes indicates how successfully intermarriage between jatis was prevented for thousands of years. As geneticist David Reich writes, there were likely many “Romeos and Juliets over thousands of years of Indian history whose loves across ethnic lines have been quashed by caste.”

On Why Caste Emerged in India

While the processes by which caste came about are now fairly well understood, the question still remains as to why such an airtight system emerged in India, and evolved in a way with local thinking so as to acquire ideological backing. It is fairly well-established that the system hardened particularly during the Gupta (320-550 CE) period, but the Gupta period was not necessarily the cause of the hardening of caste throughout all of India (it hardly expanded beyond the Ganges valley). Rather, social phenomenon that became increasingly common in the period were reflected by the Gupta Empire’s philosophy and social structure. Many phenomenon impacted India around this time: Buddhism began to decline, and trade with Rome and China dried up with the fall of the Western Roman and Han empires. This may have led to a greater ruralization in India as agriculture and self-sufficiency grew in importance relative to trade.

But according to Razib Khan, the biggest factor in the changes India experienced during this period was that classical India’s expansion boom ran its course and the frontier between cultivable land that could be brought under the purview of Indic civilization, and hilly and forested areas became clearly defined. Although India was known for its large population even in ancient times, it, like many regions in antiquity, was still relatively “empty, and did not become “filled up” until well into the first millennium CE.

The following is a lightly-edited exchange between us on this topic:

Razib Khan: I suspect that the [reason] endogamy [between castes] became noted [during the Gupta era] is [because] the boundary between Sanskritized and non-Sanskritized population [the adivasis (tribals or “scheduled tribes”)] stabilized due to ecological considerations. The social system of the Indian lowlands was not applicable to the uplands, so when all the “virgin territory” was assimilated into the cultural complex, it ran up against ecological limits (people in the hills were not good candidates for the stratified Hindu system).

Akhilesh Pillalamarri: Are you suggesting that because the adivasis were not assimilated into the system, the pace of Sanskritization slowed, and the upper-caste people in the agricultural caste societies began to notice that some of the lower orders among them looked like and exhibited cultural similarities to the adivasis, and thus ought not be intermarried with?

Razib Khan: Yes. Though I think the instinct toward separation is older…probably an old feature that goes back to the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC)…The groups were culturally very different and so intermarriage was mitigated.

Akhilesh Pillalamarri: If it goes back to the IVC, your assertion would be (to simplify a bit) that jati was IVC or proto-Dravidian, and the Aryan varna system eventually got layered onto that? (See Part 3 of this series for further clarification on jati and varna.)

Razib Khan: Yes. To be clear, I’m not sure. But the caste differences in south are not just Brahmin versus non-Brahmin. And other Indo-European groups don’t have jati. [Iran had a three-way conventional Indo-European caste system similar to the Aryan varna system.] So it’s plausible [jati caste] was an IVC innovation….Perhaps if I had to guess, the IVC is a West Asian culture pushing into subtropics. This shock/adaptation might have resulted in the segmented system you see in India. Speculation.

It should be noted that the sharp distinction between settled, agricultural peoples, and their tribal or nomadic neighbors is a common theme in human history. Generally, peoples who sow and plough the land develop a sense of refinement and civilization in opposition to their neighbors. One of the world’s oldest stories is the Sumerian tale that debates the merits of growing grain versus herding sheep. In Chinese and Persian histories, there is a tension between settled populations and nomadic neighbors. In India, this sentiment went in the direction of associating the produce of the earth (vegetarianism) with not only civilization, but ritual purity.

Conclusion

Despite the persistence of caste, it is clearly on its way out gradually. Modernity, global capitalism, and the laws that come with being a liberal democracy have opened the doors to intercaste and interracial marriages in countries throughout the world, including India. Even through inter-caste marriages are still rare, they are growing, and this growth is enough to lead to the eradication of differences between castes over the next few hundreds of years. Intermarriage and the “confusion of castes” (to use traditionalist terminology) will make caste meaningless as a biological unit in the future.

The true diversity and multiplicity of origins of India’s people was not appreciated fully until recently, and the revolution brought on by genetics, a method derived from objective science, not ideology or bias, though there will likely be controversy over the origin of the Aryans for a long time, owing to the investment the Hindu-right has in the notion that modern Hindu Indians are completely indigenous to the subcontinent (justifying the other-ing of non-Hindus). After all, historical records, literature, and archeology created in India only record certain things such as war, pottery, and poetry that occurred in India, so could be used to support the idea that there was no migration into India after its initial settling. But the science proves otherwise.

While it is important to remember that caste is not the end-all of Indian history and society, as India’s historical civilization developed, kingdoms rose and fell, and religion and trade flourished, brimming beneath the surface was an enormous churn of various peoples mixing in different proportions. The human diversity of the Indian subcontinent, home to a quarter of the world’s population, whose people descended from ancient Indians, Middle Easterners, Central Asians, and Southeast Asians, is truly amazing. Even if the system that resulted from this mix led to much personal suffering and misery, it also created a civilization that was open to difference, heterogeneity, interesting ecological management techniques (as different castes utilized only certain resources in certain manners), and the preservation of unique customs. India would not be what it is today without its previous history of integration, rather than total assimilation, of new peoples into into its society.