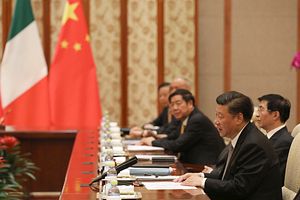

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s upcoming visit to Rome on March 22 will be an important test of China’s diplomatic and economic clout. Claims that Italy has decided to sign an agreement for official participation in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) led to a rebuke by the U.S. Trump administration, which in turn brought to surface divisions within Italy’s populist coalition government.

As the first G-7 country to sign a memorandum of understanding on the BRI, Italy’s participation would carry large symbolic weight for China. But this would hardly be enough to legitimize the BRI amid a global backlash against it and Beijing’s own struggles with piling debt and a slowing economy in the throes of a trade war with the United States. Instead, U.S. diplomats correctly warn that it would harm Italy’s own reputation.

The recent Italian pivot toward Beijing that underlies this decision is as fickle as the BRI itself. For all the overtures to China that the populist government in Rome is making, Italy has not yet settled on what relationship it actually wants with China.

Over the last decade Italy has received around $23 billion in investment from China, making it the third largest European recipient of Chinese FDI. ChemChina’s takeover of tiremaker Pirelli was the largest in the EU and overshadowed the build-up of stakes in energy companies ENI, ENEL, and CDP Reti, and in hallmarks of “made-in-Italy” like Fiat and Ferragamo.

While Beijing’s shopping spree for Italian firms raised some eyebrows with previous governments, the current one is eager to attract even more money. Italy hopes to offload ailing airline Alitalia and secure greenfield investments that grow the country’s economy and create local jobs. The economic rationale for China to indulge this remains unclear. Most of its European investments so far have been driven by the Made in China 2025 strategy, which aims to make Chinese firms competitive in high value-added industries.

For years Italy’s China policy has consisted of a growing volume of diplomatic visits and countless conferences, but little in the way of tangible outcomes. What is new about the current government’s trajectory, besides the decisive rhetoric, is a considerable downplay of the risks associated with closing ranks with China.

The change of course is largely the work of Michele Geraci, undersecretary of state in the Ministry of Economic Development. Geraci, who has himself spent a decade in China, has largely sidelined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs by establishing his own China Task Force and by taking four trips to China in the second half of 2018 alone, including with Economy Minister Giovanni Tria and Deputy Prime Minister Luigi Di Maio.

The proposition behind Italy’s new policy trajectory is that Chinese investment will help finance its ambitious fiscal reforms, such as the new basic income for the poor, and that cooperation with China in Africa will curb migration flows in the Mediterranean. These ideas have been met with contempt by Italian academics and demonstrate the unrealistic and misplaced goals of Italy’s China policy.

Indeed, Geraci’s enthusiasm for China is not shared across the board. Two-thirds of Italians view China unfavorably, the largest proportion in a European country. Even more doubt its human rights track record.

The debate over Huawei and 5G shows more cracks in Italy’s China policy. Geraci seems to see no national security risks, but members of the governing Northern League party don’t share his view. Some of them are pushing to exercise Italy’s domestic investment screening policy, dubbed “golden power,” to revoke the auctioned 5G spectrum. Last month the Ministry of Economic Development rushed to dismiss a leaked claim that Huawei might indeed be banned from 5G contracts. Notably, Italy was one of the original proponents of the EU investment screening directive before the populists’ recent back-and-forth on it.

Italy’s strategy is similarly divided when it comes to including its ports in the BRI. At one stage or another every major Italian port has competed for a share of the BRI pie. In February, not long after Geraci was in Trieste to nudge a decision to make it the main Italian node for the BRI, Venice signed a memorandum of understanding to partner with the Chinese-run port of Piraeus in Greece.

Lingering skepticism about Chinese objectives and the benefits to Italy of supporting its global advance suggest that this policy might not outlive the current government – all the more since it appears tied significantly to Geraci himself. Given this is the fifth Italian government since Xi Jinping’s ascent as China’s top leader in 2012, its pivot to Beijing should not be exaggerated in the grand scheme of things.

This is not to say that Italy should not pay greater attention to China, but rather that its priorities are misguided. Long term, Italy will be better served by aligning with the rest of Europe instead of splitting it further. The country’s short-term economic motives provide a valid rationale for seeking a beneficial partnership with Beijing, but unity in the bloc is the best way to deliver this. As the European Commission wrote in its newly-released “strategic Outlook on EU-China,” only a united Europe can balance China’s leverage and ensure that relations serve the interests of both sides.

Philippe Le Corre is a senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School and a non-resident senior fellow with the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Carlotta Alfonsi is a research assistant at the Harvard Kennedy School.