Following one of the most dramatic political crises in the recent history of South Asia, Sri Lanka’s government budget for 2019 was approved by the majority of the parliament on March 12. The 2019 budget was supposed to be presented to the parliament in November 2018, but President Maithripala Sirisena’s unexpected (and later overturned) decision to change prime ministers in October 2018 pushed back the budget. Later, a Vote of Account was passed by the parliament to provide finances until the budget could be presented in March.

The political turmoil, which surrounded the country with great uncertainty, took a toll on the economy. With the rising political instability in light of the fall 2018 constitutional crisis, three agencies downgraded Sri Lanka’s credit rating.

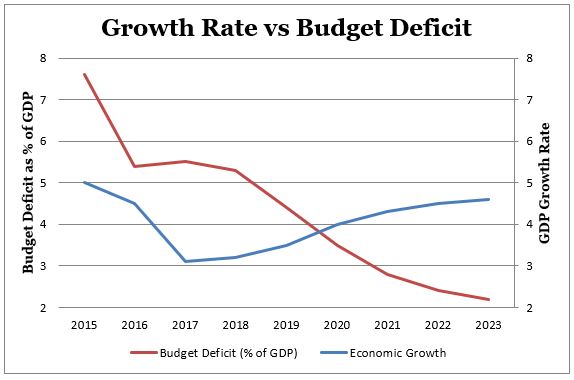

On top of that, economic growth in the fourth quarter of 2018 dipped down to 1.8 percent from 3.2 percent reported in 2017. Although the entire reduction of quarterly growth cannot be attributed to the political crisis, it is quite clear that a very significant portion of the slowdown was a result of the political instability. This resulted in the annual growth rate growing just slightly, reaching 3.2 percent in 2018 from 3.1 percent in 2017. Economic growth continues to be stagnant. This year expected growth is 3.5 percent, rising to 4.0 percent in 2020. Amid this outlook the government will seek to bring down Sri Lanka’s budget deficit to 4.4 of GDP in 2019 and 3.5 percent in 2020 to fulfill pledges made the IMF when the country obtained financial support to resolve a balance of payment crisis in 2015.

Budget Challenges

The 2019 budget was prepared amid this challenging economic environment, and reflects a variety of sometimes conflicting goals. First, the government feels the pressure to boost the country’s growth rate, which has been low for the last few years. Second, and related, the government must try to boost its popularity in light of the presidential and parliamentary elections due in 2020. In addition, the government is compelled to decrease macreconomic instability by reducing the budget deficit; increase tax revenue and the tax base; and rationalize expenditures as a part of its promises to the IMF. On top of all that, the government is supposed to manage massive debt repayments due in 2019 and 2020.

Data from Sri Lanka budget estimates and the Department of Treasury.

According to the budget estimates, the Sri Lankan government expects to reduce the budget deficit to 4.4 percent of GDP in 2019 from the 5.3 percent ratio recorded in 2018 and subsequently reach a budget deficit of 3.5 percent of GDP in 2020, in line with the agreements with the IMF. However, as ambitious the targets are, recent experience suggests that meeting budget deficit targets are very tough; more often than not the government has failed to achieve such goals. In 2018, the budget deficit target was 4.8 percent of GDP but Sri Lanka ended up recording a deficit of 5.3 percent, largely due to a failure to increase tax revenue up to the targeted level.

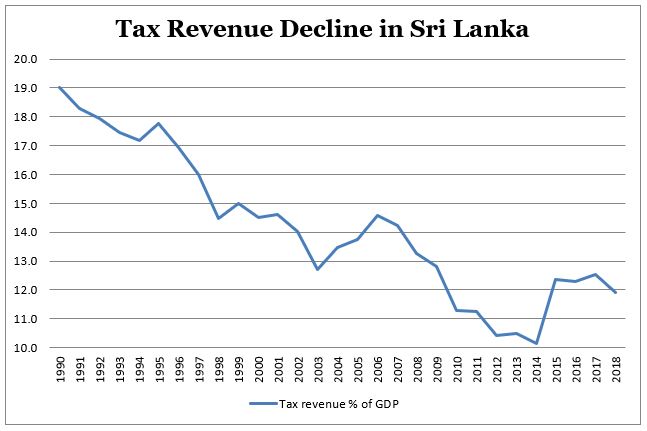

The consistent failure of the government to meet budget deficit targets is largely due to issues regarding tax revenue. Over the last two decades or so, Sri Lanka’s tax revenue-to-GDP ratio has become among the lowest in the world. In 2014, the tax-to-GDP ratio dipped down to 10.1 percent; since then, numerous efforts were put toward increasing tax revenue. Thanks to that focus, tax revenue increased to 12.6 percent of GDP in 2017. However, the tax revenue-to-GDP ratio saw another slight decline in 2018 as it fell to 11.9 percent, largely due to the reduction of tax revenue from external trade. However, the government is optimistic that it can raise tax revenue to 13.3 percent of GDP in 2019 and meeting the budget deficit target of 4.4 percent would largely depend on achieving that. Though it may seem an overly optimistic target, the government might be able to pull it off if the recently introduced Inland Revenue Act results in a significant increase of income tax collection.

Data from the Sri Lankan Department of Treasury and the World Bank.

New Income Tax Laws

To stem the consistent fall of the tax revenue-to-GDP ratio in Sri Lanka, the government introduced a new Inland Revenue Act in 2017 with the major aims of increasing the income tax net, simplifying the tax system, and moving toward a more progressive taxation system. The Act came into effect in April 2018 and increases the general corporate tax rate to 28 percent in addition to the rationalization of tax exemptions provided for both corporate income and employment income. Due to this, it is fair to assume that the revenue generated through income tax will increase considerably.

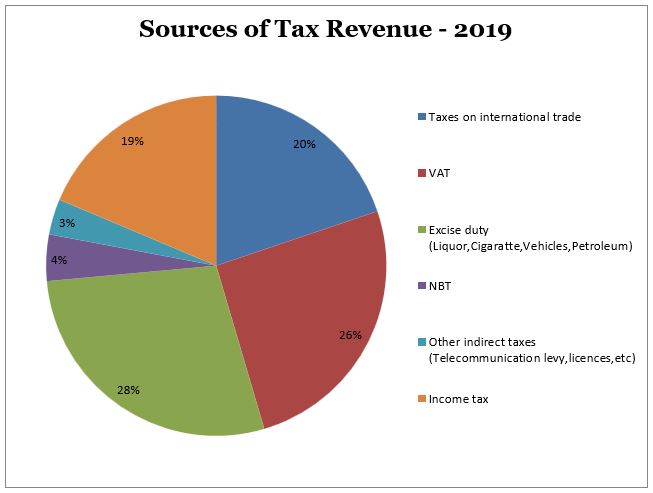

However, Sri Lanka’s taxation system is very regressive, like in most developing countries, and only about 20 percent of the tax revenue is generated through income tax. Almost 80 percent of the government revenue is generated through taxes on goods and services such value-added tax, custom duties, and excise duties. This means that a large portion of the tax burden is borne by the common people, and those who are rich pay a relatively lower share of their income as taxes. The heavy reliance on taxes on external trade is largely due to the large informal sector of the Sri Lankan economy and a strong industry lobbying to keep up high levels of protectionism by imposing taxes on imports.

Less than 20 percent of the total tax revenue of Sri Lanka is raised through income taxes. Data from 2019 budget estimates.

Progressive steps such as the introduction of a new Inland Revenue Act and the adoption of new technology by the Inland Revenue Department may help to overcome the issue of taxing the informal sector and increase the tax base, but it will take some serious political effort to reduce taxes on the external sector without being influenced by domestic industry lobbying.

Sri Lanka’s Debt Crisis

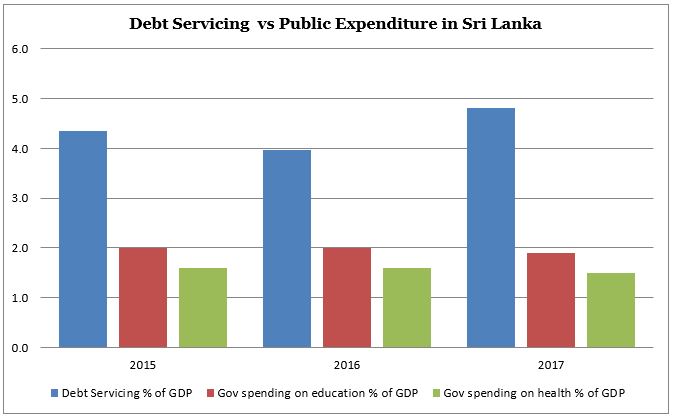

However, a budget is about not only balancing taxes, spending, and growth. In Sri Lanka, public debt repayments have become the largest element of government spending and the amount keeps getting bigger and bigger. In 2017, government spending on health and education was 1.5 percent and 1.9 percent of GDP, respectively, while government spending on debt repayments was 4.8 percent.

Data from the Central Bank of Sri Lanka and World Bank.

The significant rise of the debt repayments is largely due to the increase of foreign commercial borrowing from international capital markets. Sri Lanka entered international capital markets in 2007 with its first international sovereign bond issue worth $500 million. Since then the country has issued international sovereign bonds more than 10 times. This has resulted in not only a significant rise of debt repayment, also increased Sri Lanka’s vulnerability to facing balance of payment crises.

The 2019 budget is very crucial from a debt management point of view, largely due to the massive debt repayments starting from 2019 due to the maturity of sovereign bonds. Debt repayments amounting to $5 billion will come due between 2019-2022 as bonds issued about a decade ago mature. $1.5 billion in sovereign bonds will mature this year; another $1 billion each in 2020 and 2021, and an additional $1.5 billion in 2022.

Nonetheless, Sri Lanka was able to pay the debt installments due in January 2019 due to sovereign bond maturity without much hassle, largely thanks to the good practices carried out by the Central Bank in foreign reserve management over the last year. Despite the significant drop of the exchange rate throughout 2018, Central Bank intervention to the exchange rate market was very limited. On top of that, the country has been receiving financial assistance as per an agreement between Sri Lanka and the IMF to receive an Extended Fund Facility (EFF). With these policies, the country was able to maintain a sufficient level of foreign reserves and successfully settled the sovereign bonds, worth $1 billion, that matured in January.

The 2019 budget has to manage these massive debt repayments even while reducing the budget deficit and lifting up growth. Large debt repayments mean that the government has to cut other expenditures or raise tax revenues significantly to reach the budget deficit target of 4.4 percent of GDP in 2019.

The government has done well in terms of fiscal consolidation in the last few years. Sri Lanka was able to achieve a primary surplus in its government budget of 0.6 percent of GDP in 2018. However, growth was still stagnant and the government will need to increase it and showcase some development, given the two big elections due next year. By this time in 2020, we will know how politically and economically successful this year’s budget was.

Umesh Moramudali served as a journalist and a columnist in a national newspaper in Sri Lanka for five years before pursuing a Master’s of Economics at the University of Warwick.