With 412 films to his credit, veteran Pakistani writer, Nasir Adeeb, needs no introduction, especially after recently being awarded the Presidential Pride of Performance award for his contributions to Pakistani cinema. Having started out as a clerk in the once prolific Pakistani film industry, Lollywood, Adeeb’s early days as a struggling writer were filled with hardships and self-doubt. At the time, the film industry was exceptionally hard to break into. Even though he had a number of published novels to his credit – the first being a spy fiction story that was published when he was just a student in ninth grade – the writer dreamed of scripting blockbuster hits for the big screen.

Adeeb got his first big break in the 1970s, when his film, the 1975 Punjabi cult classic, Wehshi Jatt, took local cinema by storm. But he truly became a writing star only after his second film, the iconic Maula Jatt, a follow-up to the first. Maula Jatt broke box office records and ran for two years in cinemas across the country, despite numerous attempts by the government to ban it for being too violent. Now, 40 years later, Adeeb is awaiting the June 2019, release of young director Bilal Lashari’s reboot of Maula Jatt, titled The Legend of Maula Jatt, with a script also penned by Adeeb.

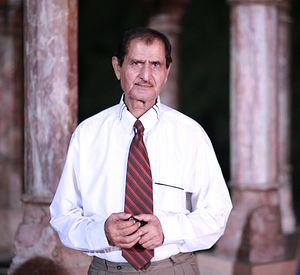

The writer — whose career arc spans over five decades — sat down with The Diplomat in an exclusive interview about his fascinating career, the demise and rebirth of Pakistani cinema, and Adeeb’s role in creating a new subculture of film, known as gandasa, which forever changed the face of Lollywood.

Nasir Adeeb and Bilal Lashari. Photo by Meem Noon Photography.

Your foray into the film industry starts with a very interesting incident. Could you tell us what drove you from writing novels to writing for film?

I had just been hired as an assistant program producer for PTV [the state-owned Pakistan Television Corporation] in 1971 when a friend of mine told me that he’d recently seen an advertisement in a local newspaper about a movie being made based on my novel, Aswa. When I saw it, I noticed I hadn’t been given any credits for the film and immediately went to the producer’s office. When I met him, I politely requested the producer to give me credits for the film; it was the least he could do. Not only was he dismissive, but he also threatened to throw me off the second floor of his building.

I was livid and went straight to a senior civil judge, Sheikh Abdur Rashid. I told him I wanted justice but didn’t have any money to pay for his services. The judge, God bless him, sent me with a police officer back to the producer’s office with orders to handcuff the director, producer, and writer of the film and bring all of them to the police station. When we got to the office, it just so happened that all three of the men were there and were immediately taken into custody. They were terrified. Within an hour, the matter was resolved; not only was I assured that I’d be credited for the film, but I was also paid on the spot. That unpleasant incident marked my official introduction into Lollywood.

How did your first film, Wehshi Jatt, come about?

I was in my 30s at the time and it was the first story I’d written for cinema. After writing it, I read it out to one of the industry’s film directors, who said I had no hope in hell if I thought I was going to make it as a writer in Lollywood. Heartbroken and dejected, with tears streaming down my face, I bumped into the renowned Pakistani actors, Mohammad Ali and his wife, Zeba, along with a director, Hassan Askari. Ali hugged me and asked me what was wrong. I told him everything. That’s when Askari said he’d use my script for his next film. On August 8, 1975, Wehshi Jatt was released and was an instant hit. At that point, my career as a writer really took off. It was incredible.

Some critics say that after the ‘70s the films being produced in Lollywood were violent, vulgar, and were a far cry from the family films and love stories being made prior to this new genre of gandasa productions.

In the early ‘70s I started fighting a war – a war that I still fight – against the evil in society, through my films. In every one of my films the hero takes on the bad guys. What violence have I spread through my work? There were killings in my movies but isn’t there violence and bloodshed all around us in society? I have only reflected what I have been seeing in our country. Why is Maula Jatt alive today? Because Maula Jatt’s every dialogue is against the corrupt system.

You were talking earlier about the effect of partition on local cinema and how it developed from there…

After the partition of the subcontinent the first film to be released in Pakistan was Teri Yaad in 1948. Very few know the reason behind the title [which means “Memories of You” in English]. Now tell me; who do you remember fondly? People you have loved and lost, right? Thousands died during partition. Homes were uprooted. Families were destroyed. The film was based on this very emotion. That’s why it didn’t do well. The wounds of partition were too fresh and people were grieving, having witnessed trauma firsthand. However, Pheray, Lollywood’s first-ever Punjabi film [released in 1949] did exceptionally well because it was a comedy and made people forget their pain. It made them laugh. Film mirrors society. It always does. I wrote Wehshi Jatt when the environment in Pakistan was tense because we’d gone to war with India twice; in 1965 and 1971.

What do you make of the film industry now compared to that of the past, when you had just started out?

Not only are the tickets expensive, but also when you go to the cinema, you feel you’ve watched an expensive television drama on the big screen – not a film. That said, judging by the reaction to The Legend of Maula Jatt, I told Lashari that his film doesn’t need any publicity because it has two audiences; those who gave up watching films and those that still watch films. This production has to hit the 100-crore [1 billion] mark, if not more. I have high hopes.

A still from the upcoming Bilal Lashari film, The Legend of Maula Jatt.

What advice would you like to give Pakistan’s new generation of young, independent filmmakers who are birthing a new wave of local film in the country?

Don’t make everything an ego issue; be humble. Take Lashari for example: he looks for the best in everything and takes constructive criticism very well. When I came on board for this film, I told him I was making a re-entry into Pakistan’s new film industry with his upcoming production. There was a time when I’d have at least 10-14 directors and producers waiting in my living room every morning to meet me. Since this project began, I’ve visited Lashari’s house a grand total of 408 times (I journal everything)! Films are my passion; I don’t pay heed to anything else but the final product. As far as the young blood goes, I don’t doubt their work; however, they should make it a point to learn from those before them.

Sonya Rehman is a journalist based in Lahore, Pakistan.