With the establishment of Afghan National Unity Government (NUG), the Afghan government has been trying to get Chinese help in jumpstarting moribund peace talks with the Afghan Taliban. Kabul hopes to entice China to use its leverage on Pakistan, which hosts the Afghan Taliban leadership.

However, this is not the first time that an Afghan government turned to China for help in a desperate situation. There have been at least three other attempts in the past three decades; all of them went in vain. The piece will discuss the recent historical background of such attempts; Part 2 will focus on the NUG’s tilt toward China and its results.

There are two main reasons behind Afghanistan’s use of the “China card” to approach Pakistan over peace and security in Afghanistan. First, China has good neighbor relations with Afghanistan, but also strategic ties with Islamabad. Second, China has serious concerns over the “three evils” of terrorism, separatism and extremism not only in the region but in China as well. However, the earlier lack of particular Chinese interests in the region (compared to the driving force of the Belt and Road Initiative today) made Beijing largely unresponsive to Afghan outreach.

Najibullah, the First ‘China Card’ Player

After the failure of Jalalabad operations, the Afghan Mujahideen became better united to attack and besiege the city of Khost in 1991. The Mujahideen were fighting against the military forces of former President of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan Mohammad Najibullah. The Mujahideen forces were under the leadership of Commander Jalaluddin Haqqani, an influential commander and a native of the area, who was linked to Hezb-e Islami (Khales), one of the seven major jihadi militant groups based in Pakistan.

During the siege of Khost in 1991, Afghan Mujahideen attacked the city from three different directions. Within two weeks, they had captured not only the city of Khost but also the army posts and the airport, and they also cut the supply routes of the Afghan army from Kabul via Gardez. Najibullah had only one option to supply his men and fight against the Mujahideen: airlifts and airstrikes. However, the bad weather made this impossible.

To escape this situation, Najibullah tried to play the “China card” to influence the ongoing siege to his benefit. He hoped that, through China, he could influence Pakistan, which Najibullah believed to be mainly responsible for the continued siege of Khost. This was a last resort — Najibullah considered China along with the United States, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia to be responsible for jolting his government during the Soviet invasion. Nevertheless, irrespective of this reality, he framed his request as a humanitarian one.

Hence, on April 4, 1991, Najibullah wrote a letter to Chinese President Yang Shangkun, describing the situation as being caused “by the direct and blatant interference of the Pakistani army and militia.” The Afghan president complained that, although he had “extended hands of friendship towards Pakistan, Pakistan had ignored our sincere attitudes, and the Pakistani Junta had once again put us in front of a military challenge.” He added that his government “has [already] informed the Secretary-General of the UN [about this].” Najibullah’s letter ends by asking China to help, as it has “influence in the region and can play an important role in restoring peace and reduce regional tensions.” He notes high expectations that China will “prevent serious Pakistani violations over Afghan land, especially in the province of Khost, and stop Pakistani aggression against Afghanistan.”

There is no evidence of Beijing’s response — it was silent. Najibullah probably knew China was unlikely to react. That’s why he gave his request more a humanitarian touch. In his letter, he stated that “due to thousands of Pakistani rockets, many innocent children, women, and elderly had died.”

For Beijing, it was not possible to help Najibullah out of a desperate situation. Chinese leaders knew that shortly their allies or allies of their allies (the Mujahideen) would grab power, and hence, there was no strategic reason to pressure Pakistan, who was China’s sole strategic partner in the region — especially for the sake of the Soviet-backed Najibullah. Helping Najibullah might incur enormous costs compared to any benefits gained. Therefore, China had minimum contacts with Kabul, except for a few low-level exchanges where Afghan and Chinese delegations visited China and Kabul for conferences and seminars. From 1989 to 1992, there were no exchanges of high-level bilateral visits, no announcements of aid, no signing of MoUs, and no congratulatory messages sent on anniversary occasions — all common practices in bilateral ties prior to the Soviet invasion.

Therefore, the first Afghan attempt to play a “China card” to influence the security situation in the country fell flat, with no response from Beijing.

Rabbani’s Distress Calls to Beijing

A second attempt to involve China to stop military conflict in Afghanistan happened during the Afghan Civil War, when the Taliban were rising and becoming a real threat to President Burhanuddin Rabbani’s govt. When the Taliban gave Rabbani in ultimatum in November of 1995, demanding that he hand over Kabul to them, Rabbani — like Najibullah before him — tried to play the “China card.” He sent a letter to Chinese President Jiang Zemin on January 18, 1996, just before Kabul fell into the Taliban’s hand. Rabbani stated that the country faced many problems due to Pakistan and expressed his hope that China will play an active and constructive role in solving the Afghan problem and preventing foreign intervention.

Although Rabbani’s diplomatic initiative did not produce the desired result, it did persuade Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Tang Jiaxuan to invite Afghan Deputy Foreign Minister Abdur Rahim Ghaforzai to China on January 22-26, 1996. The two sides met on January 24 in China. According to Afghan diplomat Ghulam Muhammad Sokhanyar, who was a part of this meeting and later recalled the events in his book, the Afghan delegation described the developments related to the Afghan peace process, particularly the UN-led process and the willingness of the Afghans to get Chinese support in this regard. Sokhanyar recounts that during the meeting, the Chinese side emphasized its traditional foreign policy and supported the UN efforts to resolve the Afghan problem.

Karzai’s Request for China to Bring Peace

After the U.S.-led overthrow of the Taliban in 2001, China was “sleeping” on relations with Afghanistan, according to a former Afghan minister and a close aide to then-Afghan President Hamid Karzai who spoke to The Diplomat. It was Karzai who approached China to initiate Beijing’s proactive role in Afghanistan, especially during his second term. However, one cannot overlook the fact that Chinese engagement in the Afghan peace process would not become truly proactive until the roll-out of the BRI in 2013. Before then, China adopted a deliberate “hands-off” approach.

Karzai, like his predecessors, tried to engage China in Afghanistan in the hopes of using Beijing’s leverage over Islamabad to secure peace in Afghanistan, and thus influence the Afghan economic and security landscape.

It is in this regard that Karzai proposed a trilateral dialogue between Afghanistan, China, and Pakistan to focus on security cooperation between these three countries in 2010. Based on the proposal, the first Afghanistan-China-Pakistan trilateral dialogue at the director general level was held in Beijing on February 28, 2012. These dialogues were conducted with the aim to enhance cooperation between the three countries, maintain peace and stability in the region, and overcome challenges, including the Afghan peace process. Importantly, officials at these talks expressed their support for an Afghan-led and Afghan-owned peace process.

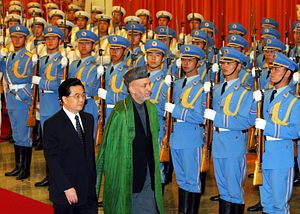

During Karzai’s 2012 official visit to Beijing, where he signed a strategic agreement with China, he also talked about the “China card” in a speech at China Foreign Affairs University. According to Karzai: “We have been of the view that China can play a very significant role in bringing Afghanistan and Pakistan together towards a cooperative environment in the war on terror and radicalism. So nobody in this region would feel that one or the other would need to rely on the use of radicalism as an instrument of policy. There China can play a significant role.”

Many trilateral dialogues between Afghanistan-China-Pakistan were held one after another; later these tripartite talks spread to Track II triangular diplomacy. In 2015, under the new NUG, the first round of trilateral Afghanistan-China-Pakistan strategic dialogue was initiated.

Karzai’s tilt toward China was more subtle than those in the past. He wanted Beijing to play a mediator role between Kabul and Islamabad, and hoped that general Chinese involvement in Afghanistan would help improve the security landscape. It can be better understood in his own words. Four years after leaving the presidency, Karzai said that “China is a very close and strategic friend of Pakistan and Chinese words with the Pakistani government carry weight… China being a great friend of Pakistan is an asset for us; we believe that China can use that asset in a way that brings about good relations between us and Pakistan and also leads to peace in Afghanistan.”

Karzai’s outreach resulted in more Chinese economic engagement in Afghanistan, and the laid the groundwork for trilateral cooperation between Afghanistan, China, and Pakistan. Later, with the introduction of the BRI, it paved the way for more strategic bilateral ties between Afghanistan and China. But there were no notable developments in the Afghan peace process during this time.

The next article will explore the NUG’s approach to China and its impact on the peace process.

The author is thankful to Halimullah Kousary, the acting director of Conflict and Peace Studies, and Borhan Osman of International Crisis Group, for reading the first draft and providing comments.

Ahmad Bilal Khalil is a Kabul-based Afghan researcher and has recently published a book on “Afghanistan and China: The Bilateral Ties (1955-2015)” in Pashto. He follows Afghan foreign policy, Islamists, regional geopolitical and geo-economic matters, and Kabul’s relations with its neighbors (especially China, Pakistan, and India), and tweets at @abilalkhalil.