This year is set to be a transformative one with considerable unpredictability. In response to China’s skyrocketing economic power and political influence across the world, “EU-China – A strategic outlook,” the newly published report by the European Commission, takes the lead on an evaluation primarily pertaining to relations between China and the European Union. The document conceives of China as “an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance,” but simultaneously as a partner.

The report “included the clearest and toughest language yet toward China in an EU document,”commented Fred Kempe in a CNBC article. Even though both media at home and overseas have set a strikingly worrisome tone on the report’s outlook, does it really imply that there might be a watershed moment ahead for the EU’s foreign policy toward China?

The world is more dynamic than static. Unsurprisingly, the report portrays mainly the underlying perspectives of a broad strata of worries and anxieties in Europe as these profound changes occur. The need to achieve a more balanced and reciprocal EU-China economic and trade relationship is revealed between the lines, which highlights the fixed feelings of the EU in the face of China’s rising strength and tremendous open opportunities at the same time.

However, it should first be clarified that despite the overreaction of media analysis, the report tends to reflect the EU’s comprehensive and profound thinking toward the re-repositioning of relations between the two sides. As a case in point, words like “engage” and “engagement” have been mentioned 13 times altogether in the report, at a much higher frequency than the discussion of competition and rivalry. This reiteration, to some extent, highlights that negotiation is the centerpiece of the EU’s pivot to China, which greatly departs from the National Defense Strategy released by the U.S. Department of Defense, for example.

Besides, to state it practically, the subsequent implementation based on the report will fall far below expectations. Hit by a range of issues, the EU is visibly divided and cluttered with aggravated contradictions. Specifically, it is exposed to scissor-style pressures: from above, through the quagmire of Brexit, and from below, from the rise of populism. The latter, with less exposure than the former, is still worrisome.

The Guardian indicates that “the number of Europeans voting for populist parties in national votes has surged from 7 percent to more than 25 percent.” Through these significant gains at the ballot box, populist parties and movements in Western Europe have enormously disrupted the region’s political landscape. Over the long run, they may wind up getting the progress of European integration bogged down by creating pushback in public opinion against any deepening reform or promotion for integration policies. And the divergence among countries in terms of immigration, the Eurozone, free trade agreements, and foreign policy will become more prominent, with limited space for consensus and compromise, finally resulting in a permanent impediment for the institutional improvement.

So where should the EU-China relationship head in this environment?

This bilateral relationship undertook a series of twists and turns since China released its first European policy documents in October 2003, which signaled that China and EU have established a “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership.” Notwithstanding the skeptics of China’s growing power, Europeans are seeking to avoid the overt confrontation favored by the White House. They don’t tend to put in place sweeping U.S.-style bans on Chinese investment in sensitive sectors, thanks to the deep trade interconnectedness between the two markets. But it does not mean that the EU will accept security risks, such as that of the 5G technology of Huawei, in order to keep pace with a crucial development.

To harness the potential of this extremely important and very complicated relationship, both China and the EU need to reconfirm their common interests and update consensus on this basis to enhance mutual trust. Scholars like Cui Hongjian state that the two sides should be aware that it is differences in the policy environment, profitability, and priorities, rather than lack of common interests, that will result in disagreement.

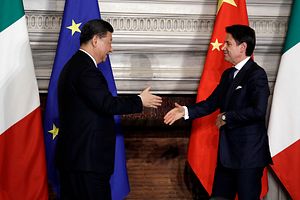

With the advance of globalization as well as cutting-edge technologies, how China integrates into the international order with the aid of the EU should be another concern for the cooperation. Starting with the fact that Italy has jumped aboard the Belt and Road Initiative train, it is time for the EU and China to jointly decide to bolster each other’s endeavors, holding fast to the chance for international cooperation in the digital area, as both parties highly value the significance of digitalization in connectivity — not only the BRI but the EU’s Europe-Asia connectivity strategy — against the backdrop of a new wave of tech innovations. For example, constructing better digital links between China and Europe in the tourism and e-health sectors may be the first step with the fewest hurdles to benefit Chinese and European people from every walk of life. Statistics show too that tourism from China to the EU has tripled in the last 10 years, rising far beyond that from other major non-EU countries. As a result, both sides reached a deal, labeling 2018 as the “EU-China Tourism Year (ECTY).”

The wind is now in the sails of these two giants. In a global environment teeming with uncertainty, EU-China relations are as consequential and subtle as ever. Any adverse action could fan flames on either side and cause twitchy political leaders to respond in ways that lead to disaster. Hence, given the current low point for EU-China relations, European governments really have to think twice whether to side with the United States in this new strategic stand-off or chart their own course.

Chen Dingding is the founder and president of Intellisia Institute, an independent think tank in China that focuses China and the world. Hu Junyang is an assistant research fellow at Intellisia Institute, with a research focus on domestic politics, media, public opinion and Chinese foreign policy.