Trans-Pacific View author Mercy Kuo regularly engages subject-matter experts, policy practitioners, and strategic thinkers across the globe for their diverse insights into U.S. Asia policy. This conversation with Romeo Orlandi – Vice President of the Italy-ASEAN Association and President of the think tank Osservatorio Asia; professor of Globalization and Far East at the University of Bologna; and former trade commissioner for the Italian government in Los Angeles, Singapore, Shanghai and Beijing – is the 185th in “The Trans-Pacific View Insight Series.”

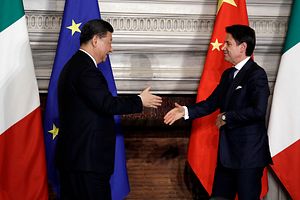

Explain the Italian government’s rationale for endorsing the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The rationale for the Italian government to endorse the BRI is at least threefold. Firstly, there is an aim to regain some ground lost in the commercial relationship with China. Twenty years ago, Italy had a 1.9 percent share of Chinese imports. Today, the share is a mere 0.9 percent. This makes it irrelevant that every year the Italian exports to China grow in absolute terms. Secondly, there is an appetite for Chinese investments in Italy since Italian companies and the government need an injection of money. Finally, we witness a more politically-oriented reason. The current government is inspired by anti-establishment sentiments and the EU is identified with the traditional order. To differentiate their position from Brussels’ mainstream, the two leading Italian parties exercise some propaganda with the hope of gaining electoral votes.

Analyze the adverse reaction of Berlin and Brussels toward Rome’s endorsement of China’s BRI.

Brussels and Berlin (even Paris has been more vocal against Rome) are afraid that Rome might break the European position on China. In a sense they have reasons to protest, since Italy is the first G-7 country to sign such an important document as the [BRI] memorandum of understanding (MOU) with China. At the same time, Italy followed the same example Germany and France set in doing business with China. They did even more than what Rome imagined (and hoped) in the MOU, of course without asking for any permission from Italy. In other words, they used their dominant position within the EU.

Assess Rome’s balancing of relations with China vis-a-vis the EU’s designation of China as a “systemic rival.”

This is a new, tougher stance by the EU. It denotes a strong difference with the Italian position. Still, the controversy is rather apparent. The China-Italy MOU contains no legal implications, nor is it a treaty. It might be a storm in a teacup (amplified by the current intra-European disputes) or a significant milestone, which I hardly believe. It all depends on the ability of the Italian government to act as an effective partner with China. From this standpoint there are many questions still lingering. It has been said that the seal of the Italian government on the MOU was purely symbolic, and consequently it looks like a favor to Beijing. The real problem is that it will probably remain symbolic, if Italy will not be able to handle it.

What is the role of Southeast Asia in EU-Asia relations?

There is a possibly productive role for Southeast Asia in the relationship between EU and Asia: find a more stringent unity to counterbalance the titanic actors, politically and economically, in the Asia-Pacific region. The ASEAN member states will soon be called to make some strategic choices since neutrality will probably be insufficient. The traditional reliance on Washington for security and on Beijing for the economic development will be increasingly difficult to be implemented because the two capitals face growing tension with each other. If some strategic decisions in Southeast Asia are to be taken, Europe might set an example but unfortunately, the EU is divided as never before.

What should U.S. policymakers understand about the foreign policy and economic relevance of Italy’s relations with China?

U.S. policymakers should understand that the negotiating power of Italy with China is now dwarfed. The technological edge with China, originally and still in favor of Italy, is losing ground. Beijing has much more political influence than Rome. In Europe the Italian government risks isolation on crucial issues. In conclusion, China for Italy is a necessity more than a choice. Italy does not have the might to break with the traditional allies, nor to establish a new friendship with China. What Italy can do is to slightly increase its exports to China and – more than that – sell its jewels. Italian companies are generally small and medium. They do not have the strength to venture abroad in globalized times and be so open to international competition. But, Italian companies possess very sophisticated technology, exactly what China needs to improve its industry and move from a quantitative model to a qualitative one, as envisaged in the “Made in China 2025” plan.