China’s increased economic and political footprint in Europe has finally caught the attention of policymakers on the continent. In a new European Union (EU) approach, for the first time, Beijing is mentioned as a “systemic rival” of Europe. According the recent document of the EU Commission “EU-China: A strategic outlook,” China is moving from a “strategic partner” (as depicted for more than 15 years in EU parlance) to a “negotiating partner.” Ideally, the EU needs to find a balance of interests with China as an “economic competitor” in the pursuit of technological leadership, and as a “systemic rival” promoting alternative models of governance.

One of the main challenges in Sino-European relations is being played out by China’s far reaching initiative, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) or One Belt One Road (OBOR), the brainchild of Chinese President Xi Jinping. The BRI, elevated to the constitutional rank by the Chinese Communist Party as a part of Xi Jinping’s “China’s Dream,” is an open competition for global leadership, and a way to reshape the international system, putting China at its center.

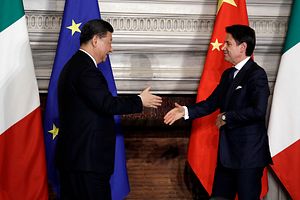

The EU Council met on March 22 to discuss a common EU strategy toward China, which would serve as a basis for the EU-China Summit to be held on April 9. Ironically, the next day the Italian government signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with Beijing to officially become a member of the BRI.

While at the start, the BRI was seen as a real opportunity for European economic recovery after the Eurozone crises, is has recently prompted new concerns. Following a “wait and see approach” on the EU side, there is a wider understanding that while the BRI promises global development, at the same time it carries daunting challenges, primarily running counter to the EU agenda favoring trade liberalization. In direct response to the BRI, the EU Commission published its Strategy on Connecting Europe and Euro-Asia, based on Western economic and institutional norms and principles, a document that completely ignores the BRI.

Chinese Strategic Partnerships With the Main Entry Points in Europe

While the EU was formulating its strategy, China was carefully targeting countries in South and Central Europe. Before Italy, 13 other EU member states had signed bilateral agreements with Beijing, officially becoming members of the BRI. It all started in 2012 with the “16+1” platform that gathered 11 EU member states and five candidate countries — all in Central and Eastern Europe — for meetings with China. Since then, two other EU countries, Greece (August 2018) and Portugal (January 2019) also signed on as members of the BRI.

Ultimately, Beijing, underlining its long-term strategy, has slowly penetrated the “softer” Central and Southern periphery of the EU with the aim to access the “core economies” of Europe, while simultaneously taking strategic control of the main shipping ports as points of entry for Chinese products.

In the framework of the China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, an integral part of the BRI, Italy represents one of the most important strategic players for China in Europe. The Chinese flagship project is the “Five Ports” initiative involving the Italian ports of Venice, Trieste, and Ravenna, plus Capodistria (Slovenia) and Fiume (Croatia), linked together by the North Adriatic Port Association (NAPA).

While Italy is not the first EU member to become a member of the BRI, it is the largest EU economy, and the only G-7 member.

The MOU between China and Italy is a very ambitious (while not legally binding) document, aiming at a strategic partnership covering a broad range of areas such as trade, investment, finance, transportation, logistics, infrastructure, connectivity, sustainable development, mobility and cooperation, also involving third countries. Notably, the area of telecommunications was left out of the agreement.

The Italian government hopes that membership in the BRI will open new opportunities in trade and investment, considering the country’s sluggish economic growth over the last two decades. Since 2001, the average GDP growth rate has been 0.25 percent compared to the 1.7 percent EU average, which has a negative effect on local markets and the purchasing power of average Italians.

With a government debt of 130 percent of the gross domestic product, Italy is hoping to finance some of its infrastructure projects with Chinese money. Since 2000, Italy has attracted a stock of $16 billion in Chinese investment.

While Chinese banks might finance some of the needed infrastructural work in Italy, there are concerns that this might lead to a new and unsustainable financial situation, adding to the economic and political strings attached to Chinese economic funding under the BRI. In BRI countries, Beijing has been accused of leveraging its economic capacity to take control of strategically important infrastructure assets, while countries have become heavily indebted to China.

The hope that membership in the BRI will open new areas of cooperation for Italian companies might look optimistic in the short term, but naïve over the long term. One should consider that the EU as a whole has not achieved more market access in China after long years of insistence. On the contrary, it is probable that the strengthening of the transportation networks and future Chinese control over infrastructure and strategic investment will, in the long term, destroy Italy’s local industries.

While the EU is trying to implement a new mechanism to screen Chinese investments in strategic areas across Europe, Italy, interestingly, abstained from a vote on just such a mechanism earlier this month. This is a significant change from the previous Italian government of the Democratic Party (PD) coalition led by Paolo Gentiloni, which in collaboration with the German and French governments had requested such a mechanism in a letter submitted to the European Commission in February 2017, highlighting growing concerns about Chinese investments in Europe.

How Europe Needs to React

Europe needs to defend its technological sovereignty, while investing in new industries that can compete with Chinese big state enterprises. One should not forget that Chinese spending in research and development has exceed that of the EU, with China spending 2 percent of its GDP, displaying the most rigorous R&D growth (accounting for nearly one-third of the global R&D spending over 2000-2015) and pledging to reach soon 3 percent of GDP.

In the new EU-China: A Strategic Outlook document, the focus is to achieve a more balanced relationship with China, based on fair competition and market access, with the goal of persuading China to commit to reforms (within the framework of the WTO) of industrial subsidies and policies.

The EU strategy is signaling an end to the unfettered access of Chinese companies in the EU market, while Beijing is failing to reciprocate by liberalizing its own market. While we still cannot speak about an alignment of interests or vision of the European countries towards China, the common strategy is a good step forward. But to effectively implement it, there should be a joint European response.

While Italy hopes that through deeper trade and investment ties with China it can boost its economy, its bargaining power can increase only if relations with Beijing will be pursued through the EU, as outlined in the EU’s 2016 Strategy on China. As it stands, Italy risks remaining the weaker partner in bilateral relations with China, as today, the BRI is a platform that provides new market opportunities for Chinese firms and capital (most of which are state-owned enterprises) at the expense of host countries enterprises.

At the same time, Italy is among the most important economic and political players in Europe, and any EU response that excludes Italy would be incomplete and unsuccessful.

Dr. Valbona Zeneli is the Chair of the Strategic Initiatives Department at the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent views and opinions of the Department of Defense or the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies.