Rates of virginity in Japan are not as high as previously reported, and socioeconomic status seems to play a role in determining heterosexual experience among men, according to our recently published study. Given our findings, it is time to reconsider the exoticization of Japanese sexual behavior, best exemplified by the BBC’s 2013 documentary, “No Sex Please, We’re Japanese.”

Since the turn of the millennium, young Japanese adults have apparently begun to lose interest in sex and intimate relationships, a phenomenon known as sekkusu-banare (literally, “drifting away from sex”). The 2010 and 2015 summary reports from Japan’s National Fertility Survey showed that more than 40 percent of never-married Japanese 18-34-years-old reported no experience of heterosexual intercourse. Naturally, these reports – along with those of other surveys on attitudes toward dating and intimacy – were met with speculation as to why Japanese youth harbored little interest in sex, ranging from measured assertions about Japanese work culture and economic stagnation to more unconventional justifications, commonly illustrated by the portrait of a middle-aged man opting out of intimate relationships with flesh-and-blood women in favor of cavorting with a video game heroine.

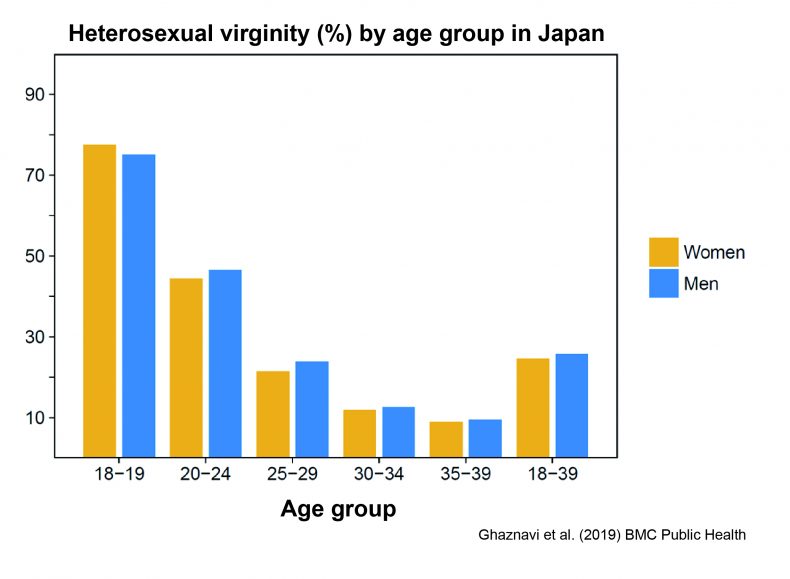

Among the slew of articles covering Japan’s supposed virginity crisis, some seemed to forget that the National Fertility Survey numbers were strictly for never-married individuals only, instead reporting that over 40 percent of all Japanese young adults were virgins (including reports by BBC and CNN). Moreover, no interest was shown for considering the virginity rates by age group. While 18-year-olds unable to lose their virginity may qualify as a tragedy in your average coming-of-age novel, high rates of sexual inexperience in younger age groups would not constitute a national concern; what should really raise eyebrows is the proportion of individuals that are not actively participating in the mating market throughout their young adulthood. With that in mind, we took a fresh look at the National Fertility Survey data.

Not unexpectedly, when we studied the total population of young adults, the virginity rate was much lower than a cursory look at the numbers for those never-married might suggest: around one in four young adults were virgins in 2015. Over the past decade, half of the population had lost their virginity by their early 20s, with one in 10 individuals retaining their virginity into their 30s. Our analyses were limited to heterosexual intercourse, as information about same-sex sexual encounters was not available; thus, the actual proportion of virgins in their 30s is most probably lower – perhaps as low as one in 20 – when accounting for minority sexual preferences.

Another notable finding of our study is that for men (but not women), income and employment were major factors associated with virginity, in precisely the direction you would expect. Among men aged 25-39 years, those in the lowest income category were 10 to 20 times more likely to be virgins than those in the highest income category. Furthermore, those who were unemployed or part-time/temporarily employed were eight and four times as likely to be virgins, respectively, when compared to those with regular employment. In other words, our data indicate the mating market dynamics at play: Money and social status matter for men.

There are no clear answers as to why these trends exist, and the lines between cause and effect become blurry when contemplating why people end up with or opt for virginity well into adulthood. For example, are some young Japanese truly losing interest in real-world relationships, instead electing to gallivant with 2-D lovers? Or is it that inherent disadvantages at the mating market lead to an increased interest in alternative sexual and romantic practices? Likely, both hypotheses harbor a degree of truth. Media buzz tends to overemphasize the former and de-emphasize the latter, which has led to an abundance of reporting on topics such as the rise of sōshokukeidanshi (“herbivore men”) who refrain from actively pursuing sexual relationships, staged flirting services catered to women, and nude sketching classes that aim to familiarize inexperienced men with the female form. While we cannot necessarily discount the effects of more exotic undercurrents, we can say that the not-nearly-as-provocative socioeconomic factors appear to be playing an important role in these trends, much to the chagrin of overenthusiastic gaijin.

While some aspects of the sexual inactivity phenomenon are certainly unique to Japan, journalists and researchers alike would be wise to withhold the tendency to fetishize the circumstances that brought us here. Believe it or not, the West may not be far behind: Decreasing sexual activity has been reported in the U.K., U.S., and Germany, stories on sexless loneliness are starting to emerge, the minuscule minority of sexually inactive individuals comprising the incel (involuntarily celibate) movement spread terror and shock, and dating simulators providing digital intimacy are on the rise. Sexual inactivity – whether voluntary or not – is not something to be exoticized or ridiculed, nor should we necessarily consider it an area of concern. While the world has made great strides in promoting a frank and nuanced discussion about sexuality, it would be in our best interest to foster similar conversations about not having sex. We could start by learning from Japan’s (in)experience.

Cyrus Ghaznavi, Haruka Sakamoto, and Peter Ueda are researchers at the University of Tokyo. Kenji Shibuya is an affiliated professor at the University of Tokyo.