The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is China’s grand plan to revive ancient trading routes over both land and sea. Since its inception in late 2013, how China has influenced Southeast Asia through the BRI has become central to the debate on China’s keynote global outreach strategy.

For Southeast Asia, the BRI is not a brand-new policy initiative. China and ASEAN states have enjoyed extensive economic cooperation in past decades and had previously worked together on many large-scale projects. Almost all regional states appear to be generally supportive of the BRI because the initiative promises to meet their infrastructure and economic needs.

Since the BRI was proposed, there has been significant growth of Chinese investment in Southeast Asia – not just in infrastructure, but also in areas such as manufacturing, agriculture, and services. If China’s growing economic importance for the region in the past decades had led to greater Chinese influence, there should be no doubt that the BRI will, by the same logic, help Beijing consolidate its regional foothold in Southeast Asia.

However, China’s activism in relation to the BRI has led to rising concerns in Southeast Asia over China using its bolstered economic leverage for strategic purposes. These concerns will likely continue to hamper China’s implementation of the BRI in Southeast Asia.

Southeast Asian states are concerned about the wider implications the BRI may have for the region. First, the BRI could undermine the centrality and unity of ASEAN. Given that most of the BRI-linked projects in Southeast Asia are organized on a bilateral basis between China and the state in question, it could weaken the current mode of ASEAN-led regionalism and over time lead to China-centric regional economic integration.

Second, a shared sentiment is emerging across the region that Chinese investment in strategically significant projects may lead to “debt trap diplomacy.” Those who are most critical view the BRI as a threat to the sovereignty and autonomy of host countries. China has been accused of using economic development as a precursor to seeking naval base rights in maritime countries such as Myanmar, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean region. Former U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, for instance, accused Beijing of pursuing “opaque contracts, predatory loan practices and corrupt deals that mire nations in debt and undercut their sovereignty, denying them their long-term, self-sustaining growth.”

Third, many regional states, especially those that have territorial and maritime disputes with China in the South China Sea, are concerned about the national security implications of relying too heavily on Chinese funding for major infrastructure projects. China’s territorialization of the disputed South China Sea has impeded its plans for launching large-scale maritime infrastructure projects under the Maritime Silk Road (MSR). Furthermore, Beijing’s support for the Chinese diaspora to play an active role in the BRI in host countries has raised wariness among the major ethnic groups in Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia.

Despite China’s repeated attempts to downplay the strategic implications of the BRI, regional states understand the initiative will greatly enhance Chinese influence in Southeast Asia and hence guard against any emergence of a China-centred regional order.

Geoeconomic Competition From Other Major Powers

Despite its short history, the BRI has sparked rivalry from other major powers such as India, Japan, and the United States. Sharing the same anxiety toward Beijing’s influence, Australia, India, Japan, and the United States agreed to promote the free and open Indo Pacific (FOIP) concept coupled with the revival of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad).

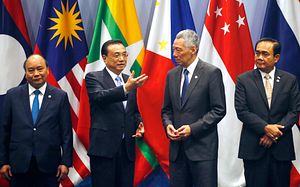

In seeking to counter the impact of China’s BRI, in August 2018, Washington announced an investment package of $113 million covering technology, energy, and infrastructure initiatives at ASEAN ministerial level meetings held in Singapore. The United States also pledged almost $300 million in new security funding for Southeast Asia. In response to the BRI, Japan launched its Partnership for Quality Infrastructure in 2015, while Tokyo has also pledged to invest $200 billion in global infrastructure.

Alternative initiatives put forward by other major powers fulfill Southeast Asian states’ desire to diversify their external economic and financial relations, offsetting the attraction of the Chinese BRI and helping these states to maximize their autonomy in relations with China. For example, Mekong countries that received many economic benefits from the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation mechanism – part of China’s BRI – expressed their support for implementing the Japan-initiated FOIP in October 2018.

The alternative initiatives also are likely to drive up the costs of China’s BRI projects in the region. Furthermore, because of these alternatives, major Chinese-backed infrastructure projects and industrial investment initiatives will be more closely scrutinized for financial feasibility, as well as environmental impact and labor standards. For example, Malaysia’s suspension of three BRI projects is a manifestation of the scrutiny on heavy debts and financial feasibility of China’s loans. One of those projects, the East Coast Rail Link, was later reinstated, but only after a hefty price cut.

More alarmingly to Beijing, the minilateral-sized Quad, inseparable from FOIP, puts much pressure on China’s security environment. China is concerned that the promotion of the Quad would send a signal to maritime countries that have disputed claims in both the East and South China Seas to adopt a hardline stance toward China, thus challenging China’s legitimacy in its maritime interests.

It appears that using the BRI as a major policy interface and promoting it in such a high-profile manner may have actually fuelled rivalry from other major powers against China in the region. It perhaps makes sense to argue that Beijing may have made a strategic mistake in rolling out the BRI and promoting it as an all-powerful policy tool.

Realizing the pushbacks against its BRI, China has taken steps to modify its approach to reduce tensions. Beijing has toned down the exaggeration of the BRI as a powerful tool. Inside China, there is a growing interest in exploring more explicit and defined rules and higher standards for China-funded infrastructure projects in the BRI participating countries. The Chinese government is also considering the possibility of redefining BRI projects to improve levels of transparency. This is because China increasingly realizes that it alone cannot carry out this large-scale initiative. We have seen some positive signs of growing collaboration between China and other major powers. China and Japan, for instance, have tentatively agreed to cooperate on infrastructure investments in Thailand.

The growing interests of other major powers in the Indo-Pacific region, as a result of the BRI, are unlikely to be excluded and ignored by China. A possible way to reduce the growing geopolitical rivalry between China and other major powers is to significantly transform the BRI from a China-centric initiative into a multilateral platform that also incorporates the participation of other major players. If such improvements to the BRI are enacted, other major powers may seriously consider their own participation in the BRI.

This article is a shorter-form version of a research paper published in The Pacific Review, a journal focused on the international interactions of the countries of the Pacific Basin. The Pacific Review covers transnational political, security, military, economic and cultural exchanges in seeking greater understanding of the region.

Dr Xue Gong is a research fellow in the China Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Her research focuses on China’s economic diplomacy, the Belt and Road Initiative and China-Southeast Asia economic relations. The full research paper which expands upon this article is titled: ‘‘The Belt & Road Initiative and China’s influence in Southeast Asia.’’ (Xue Gong, The Pacific Review, Nov. 2018)