This year marks several important anniversaries in China: The May 4 Movement of 1919, the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949, and the upcoming 30th anniversary of the June 4, 1989 crackdown on the Tiananmen Square demonstrations (often abbreviated as 6/4). Importantly, those of us in the West need to recognize the inconvenient truth that our values centered on democratic norms are clashing with the empirical reality of contemporary China. While 6/4 may still resonate with journalists and China watchers, the vast majority of the Chinese public has moved on.

The international media’s coverage of the anniversary tends to focus on tight Chinese security surrounding the anniversary. In addition, related articles on human rights in China often feature Chinese dissidents such as Ai Weiwei, the late Liu Xiaobo, and Hu Jia, who are frequently cited as evidence of a society that is pushing back against an authoritarian Chinese state. According to this perspective, the surveillance state is able to prevent any collective action that might resurrect the collective memory of 6/4, thus causing China to undergo some form of meaningful political change.

Although the media deserves credit for bringing to light China’s egregious violations of human rights (frequently in open violation of Chinese laws), most Chinese are not willing to take part in collective action unless their interests are directly threatened. Importantly, the West needs to ask whether heavy coverage and commentary centered on dissidents and sensitive anniversaries conveys the contemporary political and social reality of the majority of Chinese.

By focusing on fringe dissidents, this discussion on China’s rise risks missing the forest for the trees. By cherry picking individual Chinese dissidents who espouse Western democratic norms, we are neglecting the fact that most Chinese actually support the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). According to Boston University’s Joseph Fewsmith, over 85 percent of Chinese are “relatively, or extremely satisfied with the central government.” This inconvenient truth needs to be acknowledged in future discussions of China’s rise. The real story of 6/4 anniversaries today is not that of the commendable and courageous Tiananmen Mothers, but the fact that times in China have never been better, thus providing a weak incentive for Chinese to resurrect the ghosts of 6/4. Whether the West likes it or not, the CCP has delivered to the Chinese people in a way that most would have thought impossible on June 5, 1989.

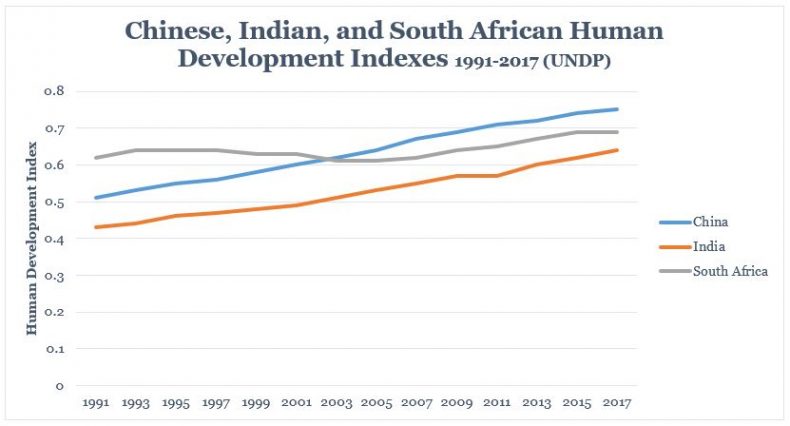

According to the United Nations Human Development Reports, which measure years of schooling, life expectancy, and income, China’s human development index has skyrocketed from .50 in 1990 to .75 in 2017 (the last year data is available). (The American score went from .86 to .92 over the same period.) As the chart below demonstrates, when compared to other developing (and democratic) countries such as India and South Africa (democratic since 1994) China has done extraordinarily well.

The CCP has transformed a mostly rural country into an economic powerhouse with a middle class that according to McKinsey & Company will include 550 million people by 2022. These represent urban households that earn between $9,000 and $34,000 per year. A simple question needs to be asked in the run-up to the 30th anniversary of 6/4: what would cause these people to rebel? What would cause them to rekindle the memory of 6/4 and risk all that China has achieved over the past 40 years?

To argue that the surveillance state prevents collective action and large protests may be true in various parts of China, but these protests do not call for the overthrow of the CCP, but instead are primarily focused on local grievances such as the illegal confiscation of land and environmental degradation. To say that the Chinese are brainwashed by nationalist propaganda also misses the point. Chinese may be heavily influenced by the state, but this propaganda works in conjunction with the empirical reality of large increases in material gains, which nearly every Chinese (urban and rural) has directly benefited from. George Washington University Professor Bruce Dickson has found that Chinese care less about overall GDP, which can be heavily allocated to elites, but more about the money that ends up in their individual pockets. Importantly, his research also reveals that 77 percent of Chinese surveyed either strongly agree or agree that “demonstrations can easily turn into social upheaval, threatening social stability.”

While a few young and courageous Chinese students inspired by Mao and Marx may be advocating for migrant workers, they are not at all representative of Chinese students. A 22-year-old Chinese college student born in 1997 has known nothing but economic progress for her entire life. Importantly, her parents know what it means to endure hardship and will likely have told her about the difficulties they encountered when they were young – for example, it was only in 1993 that ration tickets for products like meat and eggs were phased out. This same student can learn from her grandparents about the horrors of the Mao era, where tens of millions of Chinese died in the great famine of the Great Leap Forward and the political and social chaos of the Cultural Revolution. In fact, over the past 30 years China has experienced a period of stability that previous generations were denied for nearly 200 years.

We need to ask ourselves whether we are seeing what we want to see when focusing on Chinese dissidents. Anecdotally, I lectured for six years on international relations at several top Beijing universities. I was always amazed that nearly none of my students had ever heard of the various dissidents mentioned above, even though they occupied headlines in the New York Times and other Western media outlets. While part of this may because of Chinese censorship, a better explanation is that these students weren’t all that interested in the dissidents’ stories. They actually wanted to join the CCP and were direct beneficiaries of China’s “economic miracle,” thus they had a vested social and economic interest in not rocking the boat.

Are these dissidents the real story of modern Chinese civil society? While they may be fighting for a more equal and law-based China, do we see what we want to see in them and consciously ignore the bigger picture? Is it possible that most Chinese, while irritated by corruption and other forms of government malfeasance, still have faith in the structure of CCP rule and subscribe to the Orwellian verse of “no Chinese Communist Party, no New China?”

On a brighter note, those who say “Western-style” democracy failed to work in China need to take a step back and allow the story of China’s rise to continue. The theory that as a country grows wealthier its citizens will push for democratic reforms is not dead in China. In fact, China is too unequal and the middle class too small as a percentage of the overall population for such a phenomenon to occur anytime in the near future. In addition, many members of this emerging class are employed by the government, thus giving them a strong interest in maintaining the status quo.

Ultimately, journalists, policymakers, and civil society advocates need to realize that the vast majority of Chinese have little interest in marking 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen demonstrations. The West needs to understand the social and economic realities at work in China that make this anniversary a nonevent for most Chinese. We also need to question how widespread is the support for well-meaning dissidents in Chinese society at large. While many Chinese harbor similar grievances, they are not acute enough to cause them to take part in collective action against the government. By placing too much emphasis on these actors and anniversaries, we may be misinterpreting and exaggerating the importance of what are now perceived by the masses to be relatively insignificant political events and individuals. More importantly, we risk missing the wider movement in Chinese civil society, which supports the CCP – at least as long as increases in living standards continue.

Dr. Christopher K. Colley is Assistant Professor of Security Studies at the National Defense College of the United Arab Emirates. He holds a Master’s degree in Chinese studies from Renmin University of China and a Ph.D. in political science from Indiana University Bloomington. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not reflect the views of the National Defense College, or the United Arab Emirates government.