When the Czech Republic last week hosted an international expert conference in Prague on the issue of 5G security, Southeast Asian countries were not among the over 30 or so governments that were present. While that is not surprising in and of itself given the nature of the deliberations and the ongoing state of conversation more broadly in the Indo-Pacific region, it nonetheless obscured the fact that the subregion remains a key battleground for the evolution of 5G technology and will likely continue to be in the years to come.

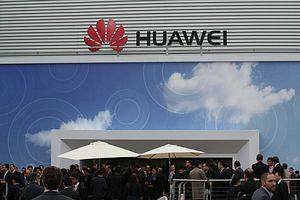

Though 5G has traditionally been used as a general shorthand for game-changing next generation wireless telecommunications networks beyond current 4G networks, it has been in the headlines of late following concerns expressed by the United States about security issues with Chinese tech giant Huawei. Those concerns have opened up a wider conversation about how the United States works with a range of countries to address these issues, which impact a host of areas including intelligence-sharing agreements it has with its closest allies as well as U.S.-China strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific region more broadly.

Among the subregional battlegrounds within the Indo-Pacific where the 5G race will play out is in Southeast Asia – with the subregion collectively making up the world’s third largest population and the fifth largest economy and serving as a key outlet for China to project its power in the region more broadly. For many of these regional states, the starting point for 5G had initially been not China, but how they could best leverage 5G technology to advance their own economic development plans. Seen from this perspective, the heightened Huawei conversation has put the spotlight on one aspect of how these countries balance the opportunities and challenges inherent in continuing to pursue their options with respect to 5G. It has also raised broader questions, such as the availability of alternatives to Huawei given its perceived, current advantages – including investments already made, lower costs, and the speed and aggressiveness in moving into certain markets – and ways to raise awareness and share experiences about managing security risks irrespective of the decisions countries eventually make.

Despite some caricatures that have been presented, as with many issues, the region as of now has seen a range of different responses among diverse countries, which is not surprising given variances seen in everything from overall development levels to technological progress. Even with respect to Huawei’s involvement in Southeast Asia and the inroads the firm is looking to make, for instance, this varies by degree. In cases like Cambodia, there seems to be quicker and more definitive movement, with the latest indication being Prime Minister Hun Sen’s signing of a memorandum of understanding on 5G cooperation on the sidelines of the Second Belt and Road Forum (BRF) and Huawei projecting progress by the end of the year. But in other cases, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, or Brunei, things are much less clear, and headlines about government officials visiting Huawei facilities or some telecommunication operators testing out certain options have been mistaken for definitive, irreversible decisions to adopt exclusively Huawei 5G technology.

A focus on just Huawei’s role in Southeast Asia is also much too narrow and misses other parts of the conversation in the region that are equally important in the evolution of 5G today. Beyond Huawei itself, some firms such as Finland’s Nokia or Sweden’s Ericsson are also playing a role in Southeast Asian states as governments and telecom operators test out options to varying degrees, be it in a standalone fashion such as Singapore or Myanmar or in an integrated fashion such as Thailand’s 5G testbed in its Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC). Some countries in the subregion are also working with local providers to assess how best to move forward on this, and Vietnam in particular presents an interesting albeit unique case in some respects where mobile telecom operators have shown an interest in either pursuing their own technology or working with other companies beyond Huawei. And some governments such as Malaysia have said they are looking into potential security implications that could arise with the 5G options they may pursue given broader concerns their own about managing their ties with China.

More broadly, an emphasis of just the current state of play with respect to government decisions in the region is also much too shortsighted. With discussions between and within governments still ongoing, whether it be on best practices to manage security risks of pursuing certain 5G options and potential effects on alignments and wider collaboration, there could be alterations in the calculus of these actors further down the line. In more democratic countries, debates may also play out in the public domain, as we are seeing in the case of the Philippines as part of broader scrutiny on President Rodrigo Duterte’s China policy. The spotlight on 5G and the need for more alternatives beyond Huawei could also drive companies and other institutions to adjust and evolve with respect to how they operate, which could in turn influence the wider business environment. And more broadly, given that it is still early days in the 5G race, it is too premature to judge whether initial trials being run and agreements reached will actually translate into reality, especially given the challenges in getting to implementation and new opportunities that could emerge as testing continues on into the future.

To be sure, one ought not to dismiss or downplay Huawei’s influence in Southeast Asia, which is important to note and could increase even further in the coming years. But amid the focus on overly simplistic linear extrapolation and fatalistic doomsday scenarios, it is worth emphasizing that the 5G battle in Southeast Asia is still very much in flux. Southeast Asia remains an interesting and important locus for competition on this front, and the battle is far from over.