All the stakeholders involved in Afghanistan seem to concur on the desire for peace and security there. However, differences emerge when it comes to on what, and whose, terms such a peaceful Afghanistan would be built. Countries involved directly or indirectly in the future of Afghanistan have largely supported “Afghan-led, Afghan-owned” peace talks. While the Afghan government under Ashraf Ghani projects a Kabul that is in control of the shape of things to come in the country, the rising indispensability of the Taliban in the peace talks and the distaste for Ghani’s leadership among a number of non-Taliban Afghan politicians appear to be eclipsing the centrality of the Afghan government. Moreover, given American outreach to the Taliban, it is pertinent to ask: What happened to the Afghan-led, Afghan-owned peace talks?

The Afghan peace negotiations, some experts have argued, are at their “most advanced stage” since 2001. In January 2019, the United States, led by U.S. Special Representative Zalmay Khalilzad, first engaged in talks with the Taliban in Doha, Qatar. The United States and Taliban agreed in principle to the framework of a peace deal. The core components of such a deal have been envisioned as the United States withdrawing its troops from Afghanistan in exchange for the Taliban “pledging” that terror groups would never use Afghan territory to stage attacks. The next round of talks saw Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar’s participation, a move believed to have lent more credibility to the negotiations among the Taliban. Per Khalilzad’s tweets, discussions on the issues of counterterrorism and troop withdrawal culminated in draft agreements while two other issues of intra-Afghan dialogue and comprehensive ceasefire saw agreements in principle. The specific details of these agreements remain unknown, but a Taliban statement after the peace talks largely concurred with Khalilzad’s interpretation. However, Khalilzad’s reference to in principle agreement on issues of ceasefire and intra-Afghan talks is not reflected in the Taliban’s statement, which says that “no agreement has been reached regarding a ceasefire and talks with the Kabul administration.” In another Taliban statement that emerged during the talks, “other issues that have an internal aspect and are not tied to the United States” were not discussed.

So far, two of the major criticisms around the current peace talks have been the exclusion of the Afghan government and Afghan women. The intra-Afghan talks in April 2019 were supposed to address these concerns, particularly the first. While a prior round of such talks had already happened in Moscow in February 2019, this informal round in April was supposed to help launch more serious negotiations. In the build-up to these negotiations, the Taliban responded to a list of 250 officials selected by the Afghan government to take part in an intra-Afghan talk, which was to be held in April in Doha, by declaring that it would engage with the officials as “ordinary” Afghans. Qatar announced a revised list, which included fewer women and no Afghan government officials as compared to the list put together by the Afghan government. Amid the differences over the size and composition of the Afghan delegation, the intra-Afghan talks were abruptly postponed. The Afghan government criticized the Taliban list as noninclusive.

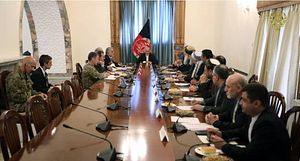

Following this, the United States, Russia, and China released a joint statement calling for an inclusive Afghan-led, Afghan-owned process. In Afghanistan, a Consultative Peace Loya Jirga consisting of more than 3,200 people from across the country was held to determine the government’s negotiating position for talks with the Taliban. It was also intended to boost the diminished image of the Afghan government as a stakeholder in the negotiations. However, key figures such as the Chief Executive Officer Abdullah Abdullah, former warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, former National Security Advisor Mohammad Hanif Atmar, and former President Hamid Karzai did not participate. Another round of talks has since occurred between the United States and the Taliban in May 2019. While there are signs of “steady and slow progress” in the U.S.-Taliban dynamic, what do these talks entail without the involvement of the Afghan government? In addition, what does the surge in violence against civilians mean for the peace process?

The Taliban has always been opposed to negotiation with the Afghan government, which it has consistently referred to as a puppet government. The United States on the other hand was stuck between the options of no negotiation or direct negotiation with the Taliban. In deciding to go ahead with the negotiations with the Taliban, the U.S. government moved away from its long-held position. In addition to being excluded from the talks, the Afghan government expressed concern about a lack of transparency surrounding the U.S.-Taliban talks. Fears about delegitimizing the already unsteady ground of the Afghan government increased with the Taliban’s announcement of its spring offensive, Operation Al-Fath (Victory), on April 12, 2019, which clearly indicated that the primary targets were the Afghan government and the Afghan security forces. Adding to the woes of the Afghan government has been the delay of the elections. Presidential elections were initially supposed to be held on April 20, with Ghani’s term ending on May 22. However, they were first postponed to July 20 and subsequently to September 28.

While the Afghan Supreme Court extended Ghani’s presidential term until the results of elections have been determined, the legitimacy of this extension is being contested. In a joint declaration, 13 of the 18 presidential candidates stated their opposition to the extension of Ghani’s term and called for a temporary government to oversee elections. With May 22 now past, the council of the 13 opposing candidates said that protests will be mobilized “within the parameters of law” if Ghani does not leave office. However, there is no clarity with regard to how an interim government’s members would be selected. There is also the question of its mandate, particularly the limitations of its mandate with regard to the peace process and what a limited mandate will mean for the intra-Afghan negotiations.

Ghani entered the presidential office in 2014 with his archrival, Abdullah Abdullah, after a power sharing deal was orchestrated by the Americans. Now, as he stays put in the Presidential Palace, critics question his legitimacy, accusing him of power lust and precipitating chaos in Afghanistan’s political atmosphere. On the contrary, his supporters credit his moves as efforts to bring stability amidst uncertainty of Afghanistan’s future. Irrespective of who is closer to reality, times are hard in Afghanistan as the president’s legitimacy and the centrality of the Afghan government in the peace talks with the Taliban hangs in the balance.

Monish Tourangbam is Assistant Professor at the Department of Geopolitics and International Relations, Manipal Academy of Higher Education (MAHE), India.

Nandita Palrecha has an MA in Conflict Resolution at the Department of Government, Georgetown University, Washington D.C.