When Chinese core leader Xi Jinping first announced his “China dream of national rejuvenation” in November 2012, he hoped to vanquish memories of “the century of humiliation” at the hands of Western powers and Japan. Beginning with the First Opium War in 1839 and closing with the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949, that century saw the waters around China fill with foreign battleships vying for control of Chinese territory.

Following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, Beijing has built formidable defense forces now capable of making foreign powers wary of any military intervention in China. Under Xi’s China Dream, these same waters are now littered with Chinese warships seeking to protect the mainland and its economic interests by controlling and “reclaiming” the “historic waters” of the South China Sea.

Beijing’s most recent attempts at controlling these waters have led to increased scrutiny and harsh criticism from littoral states and international observers. Actions taken by the PRC in recent years to assert their claims to the South China Sea have included the encouragement of Chinese fishing in foreign waters, the intentional ramming of foreign fishing boats by Chinese vessels, the movement of an offshore oil drilling rig into waters claimed by Vietnam, the construction of artificial islands, the militarization of some of the islands China controls, and the seizure of the Scarborough Shoal.

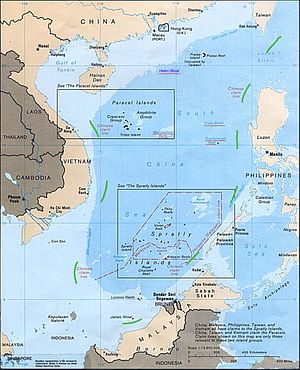

Beijing vaguely lays claim to these waters under its notorious “nine-dash line,” previously “the 11-dash line” and also referred to as the “ten-dash line,” the “U-shaped line,” and the “cow’s tongue.” The “nine-dash line” encompasses some 80 to 90 percent of the South China Sea and contradicts claims made by Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam to some of the waters, islands, rocks, reefs, and submerged shoals.

According to Bill Hayton, an associate fellow at Chatham House and author of The South China Sea: The Struggle for Power in Asia, the origin of the nine-dash line can be found in a map from the New Atlas of China’s Construction and published in 1936 by Bai Meichu, a Chinese cartographer and founder of the China Geography Society, at a time when Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China (ROC) governed from Nanjing.

After Mao Zedong forced Chiang and his armies to retreat to Taiwan in 1949, the same map published under Chiang was adopted by the PRC. The map, entitled “Map of South China Sea Islands,” included the Paracel Islands, the Spratly Islands, the Pratas Islands, the Macclesfield Bank, and the Scarborough Shoal. The PRC eventually submitted their map to the United Nations in May 2009 — greatly alarming the littoral states of the South China Sea.

Given its all-encompassing nature, the “nine-dash line” has always been controversial, yet remained largely unchallenged. In 2013, Manila brought a major challenge before an arbitral tribunal at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague, following the seizure and occupation of the Scarborough Shoal by Chinese forces in April 2012. Three years later, the tribunal ruled in favor of Manila, declaring China’s nine-dash line did not accord with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The tribunal also declared there was “no legal basis for China to claim historic rights to resources,” as China had never exercised exclusive authority over the waters. Despite having ratified UNCLOS in 1996, Beijing did not abide by the ruling, knowing the court in The Hague had no ability to enforce the ruling.

After being driven off the mainland, the ROC continued its claims to the South China Sea under their U-shaped line. Taipei, however, takes a far less confrontational approach than Beijing, having discontinued its claims following the 2005 suspension of the ROC’s 1993 Policy Guidelines for the South China Sea, according to Chi-Ting Tsai, an assistant professor of international law at National Taiwan University. Nonetheless, as Tsai argues, the guidelines were merely suspended and leave the possibility Taipei’s U-shaped line could again be revived.

Despite their suspension, the similarity between the U-shaped lines of Beijing and Taipei should lead us to ask the same questions of both governments. If Taipei’s claims are equivalent to Beijing’s ridiculous claim of 80 to 90 percent of these waters, shouldn’t the same criticism be applied to Taipei’s claim, even if it is suspended and not aggressively asserted? If Taipei’s claims overlap those of Beijing, are they even practical, given the disparate size of the Chinese and Taiwanese militaries? Would a U.S.-friendly Taipei government ever risk the same widespread condemnation by Washington and other regional powers as Beijing experienced by asserting any outsized claims? And is Taipei prepared to antagonize other littoral states of the South China Sea in pressing any of its claims?

At a seminar held in June at National Taiwan University in Taipei, entitled “The South China Sea: History as a Problem, History as a Solution,” Hayton proposed the replacement of Taiwan’s U-shaped line with an indigenous claim based on Taipei’s extensive historical archives. Hayton argued the current “nationalistic and maximalist South China Sea claim legitimizes strategic encirclement and antagonizes neighbors in an imperialistic manner.”

While Hayton did not propose a timetable, any announcement of a new indigenous claim by Taipei may be interpreted by Beijing as a unilateral attempt to drift away from its “one China” principle and could prove politically contentious in the lead-up to the January 2020 elections. While now may not be the time for Taipei to disavow its U-shaped line, if Taiwan truly wants to preserve and grow its identity as a nation separate from China, it should eventually make its own distinct claims, consistent with UNCLOS, on the waters of the South China Sea.

Gary Sands is a Senior Analyst at Wikistrat, a crowdsourced consultancy, and a Director at Highway West Capital Advisors, a venture capital, project finance and political risk advisory. He has contributed op-eds for Forbes, U.S. News and World Report, Newsweek, Washington Times, The Diplomat, Asia Times, National Interest, EurasiaNet, and the South China Morning Post.