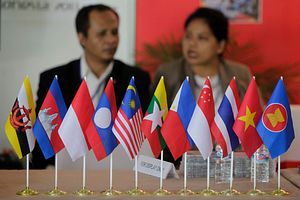

ASEAN leaders will meet for their 34th summit on June 23, preceded by several ministerial preparatory meetings that will take place starting from June 20. As Thailand is the ASEAN Chair for 2019, the ASEAN Summit will be chaired by Prayut Chan-o-cha, in his first major regional event since he was selected to continue as prime minister following the elections in Thailand in May 2019. There are serious pressing issues for ASEAN to address and divergent views can be expected from ASEAN member states on how ASEAN should position itself to face the challenges it faces. Thailand’s leadership will be key in guiding and shaping ASEAN’s response and presenting a united front in dealing with the disruptions the region faces.

It is the norm for all ASEAN Chairs to use a theme to define their chairmanship. Thailand has selected the theme “Advancing Partnership for Sustainability.” In a nutshell, Thailand hopes to advance ASEAN’s progress to keep pace with the changes taking place including preparing for the new economy. Bangkok also recognizes that ASEAN needs to strengthen partnerships with dialogue partners and other institutions in meeting the growing challenges and wants to ensure that ASEAN’s policies and community building efforts are sustainable. While Thailand works to realize the deliverables under its theme, it also has to shepherd ASEAN through the present geopolitical and economic uncertainties that the region faces. Its leadership of ASEAN during these trying times will be closely watched.

ASEAN is in for a period of regional uncertainty as a result of the heightened strategic competition between China and the United States. The rivalry between these major powers shows no sign of abating, with the U.S. labelling China a revisionist power while Beijing has indicated that it will not succumb to pressure and is prepared to confront Washington over the long term. It is not clear how long this uncertainty will last nor what the final outcome will be. Even as it tries to address and adjust to this latest flux in the region, ASEAN has to simultaneously deal with other pressing issues and disruptions such as the negotiations with China on a Code of Conduct to govern behavior in the South China Sea, the unravelling of the free trade system, uncertainties over the future of the multilateral trading system and globalization, increasing protectionist tendencies, the emergence of identity politics, and the urgent need to adjust to the new realities of the digital economy.

These profound challenges need to be addressed even as ASEAN member states continue to cope with existing transnational nontraditional challenges that pose real and present dangers, such as terrorism and violent extremism, drugs, human trafficking, maritime security, and cyber challenges. On top of all that, there’s the recent Rohingya issue in Myanmar, which has put a dent on ASEAN’s credibility over its inability to address a serious human rights issue in its own yard. Each ASEAN member will also have its own domestic and external priorities and other national concerns that might undermine its ability or willingness to lend its full weight to a regional and coordinated response to these growing challenges.

The key question is whether ASEAN, despite its 52 years of existence and its hard-earned reputation as a successful regional organization still has the agency, wit, and tenacity to navigate and survive the emerging and seemingly intractable challenges that it will have to face going forward. Insistently, questions continue to be raised about the robustness of ASEAN unity, if assurances of ASEAN centrality appear hollow, and the impact of major powers in influencing policies and the positions of individual ASEAN members countries.

Taking Stock of the ASEAN Community

As a strategy, ASEAN hopes to realize an integrated, well-connected Community by 2025 as envisioned in its Vision Document 2025. A key aspiration that would do much for the regional grouping if realized is the establishment of a common market and production base. That’s an ambitious, but certainly doable aspiration — provided each member state is prepared to make the domestic changes, adjustments, and sacrifices needed to realize this goal while at the same time coping with the external shocks and disruptions they now face.

Given the structural uniqueness of ASEAN, in particular decision-making by consensus, it has been no mean feat for ASEAN to have progressed this far over the past 52 years of its existence. This progress is not only in areas considered low-hanging fruit, which more often than not are technical and stand to benefit all member states, but in substantive areas across all three pillars that define how ASEAN is organized, namely political-security, economics, and socio-cultural. ASEAN has made real progress in forging regional approaches to combat common threats and challenges such as terrorism, violent extremism, cybersecurity, transnational crime, nontraditional security issues such as human trafficking, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief preparedness to name a few, some of which are cross pillar undertakings.

ASEAN economic cooperation has moved ahead since the signing of the ASEAN Free Trade Area Agreement in 1992. Individual member states have made progress in domestic economic progress partially due to membership in ASEAN, benefitting from the peace and stability that the grouping has brought to the region, as well as the ASEAN agreements both intra-ASEAN and with external partners forged over the years.

Much play has been given to the collective profile of ASEAN, such as its market size of 640 million, growing trade with the world (at $2.57 trillion in 2017) aided to a large extent by the grouping’s network of free trade agreements, its annually increasing GDP figures ($2.8 trillion in 2017), and growing foreign direct investment (FDI), $137 billion for 2017. These cumulative figures have been used to suggest that ASEAN is poised to become the fourth largest economy in the world by 2030, and makes for good profiling of ASEAN’s success.

What these figures in fact indicate are that if ASEAN were a single state, it would certainly be a formidable global economic player. However, breaking down these figures to the performance of each member state reveals the wide disparity that exists within the grouping. The ASEAN Statistical Yearbook 2018, published by the ASEAN Secretariat, reveals this disparity based on the statistics of each member state. For instance, the GDP per capita for Singapore and Brunei are in the five figures whereas the rest of ASEAN’s member states are still in the four digit mark. The inflow of FDI into the region is also not evenly spread. Some member states attract large inflows of FDI annually whereas others do not. Of the $137 billion in FDI ASEAN recorded in 2017, Singapore got slightly over $62 billion, followed by Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines at $23 billion, $14 billion, and $10 billion, respectively.

ASEAN’s first phase of economic integration ended in 2015, and it is now in the next phase guided by the ASEAN Economic Community Blueprint 2015-2025. Closer economic integration will require the following issues to be addressed.

Low intra-ASEAN trade: With intra-ASEAN trade at about 23 percent of ASEAN’s overall trade figures, any flux in the external trade environment would impact the health of ASEAN’s external trade. ASEAN has set itself the target of doubling intra-ASEAN trade by 2025 as a buffer against over-reliance on global trade. This would require adjustments and commitment by each MEMBER STATE, including improvements in infrastructure connectivity within ASEAN to facilitate cross-border imports and exports as well as complementary production activities;

Controlling non-tariff barriers: While member states have largely implemented the tariff removal/reduction targets agreed under the AFTA and the exclusion lists have been shortened, there has been a concomitant increase in non-tariff measures (NTMs) within ASEAN from 1,634 to 5,975 between 2000 and 2015. NTMs undermine the tariff free environment that AFTA seeks to promote.

Bridging the development gap: There is a wide gap in the economic and development levels of each member state. The Initiative for ASEAN Integration (IAI) was established for the specific purpose of narrowing the development gap within ASEAN. However, the gap remains wide. Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and to a lesser extent Vietnam continue to lag behind the other ASEAN members. While IAI efforts help, more needs to be done to move these countries up the development ladder, including national efforts by the lesser developed member states to attract more FDIs into their economies.

Overcoming domestic hurdles: ASEAN plans and agreements to realize a common market and production base have to be implemented at the national level, which is the responsibility of each member state. Each has differing domestic constraints, challenges, and pressures that would make national level implementation of ASEAN agreements less of a priority. Even if the member state wants to pursue implementation, there could be capacity shortcomings, national legal hurdles, resource constraints, and domestic political difficulties that some member states might face.

Seeing through existing agreements: Some agreements might be difficult for some member states to implement even though they have agreed to these in principle. One example would be the movement of labor within ASEAN. Countries such as Singapore and Malaysia would be cautious in agreeing to allow unfettered movement of labor as this could result in a flood of unskilled labor movement from the less developed member states to the more developed states.

ASEAN economic cohesion is still work in progress, but now requires greater determination and resolve to realize its goal of closer economic integration. There are new challenges to be addressed such as the present trends against multilateral trading arrangements, growing sentiments against globalization, and increasing protectionist tendencies. These will be further complicated by the uncertainties generated by the heightening U.S.-China trade dispute. While each member state would have to make its own adjustments and policy changes to navigate and mitigate the effects of these global trends, ASEAN as a grouping must continue to speak out against these trends and argue strongly for the preservation of a free, multilateral trade system governed by international rules and norms.

ASEAN’s US-China Dilemma

The recent U.S.-China tensions, which is increasing in intensity, place ASEAN in a difficult position. Both countries are long-standing and important partners for ASEAN. In November 2018 Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong remarked that ASEAN would not want to be put in a position where it had to choose sides. The dynamics will be complicated if each ASEAN member leans toward one or the other power, which would then make it impossible for ASEAN to come to a common position on this rivalry. Realistically, there is nothing that ASEAN can do to help both sides resolve their differences. This is a confrontation of the big boys and ASEAN does not have the weight to influence the outcome.

Bilaterally some member states might already be in the invidious position of having taken sides, especially those member states that depend significantly on economic largesse from China. Most ASEAN members count on China as their most important trading partner. The United States too is an important partner for ASEAN member states for trade, investments and, for some members, access to defense technology and military equipment. Each member would have its own internal position regarding relations with China and the United States.

It is expected that this major power tussle could be a test of ASEAN unity. It would do the grouping no good if member states were split and unable to come to a common position because of their affiliation, closeness, and dependency on one power or another. ASEAN’s credibility would be undermined. As this year’s chair, Thailand must forge a common ASEAN position on the U.S.-China strategic competition, even if it only results in expressions of concern over the impact and implications for the region and urging both sides to resolve their differences peacefully through negotiations.

Although ASEAN could suffer adverse consequences as a result of this latest China-U.S. strategic competition, it like the rest of the world is a spectator. A serious worry for ASEAN member states is the potential of a confrontation between China and the United States in the South China Sea leading to a conflict. This is ASEAN’s backyard and any tension or conflict in this area would have significant consequences for the stability of the region. The U.S. has made it clear that it does not recognize China’s claims in the area and is determined to ensure that China’s activities in the area do not go unchallenged, as manifested by the recent enhancement of Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the South China Sea by U.S. naval vessels.

The presentations by the Chinese defense minister and the acting U.S. secretary of defense at the recently concluded 18th Shangri-La Dialogue laid bare the positions of both sides. Both made tough statements about their respective resolve and determination to defend their national interests if push came to shove. This was high-level posturing by the top defense officials of both countries. Naturally the presentations were not an indication that war was imminent, but more a representation of the stakes involved in worst-case scenarios.

For ASEAN such talk is worrying as the diminishing atmospherics would have negative implications for the regional security and economic environments. Clearly if the U.S.-China situation deteriorates further, ASEAN would have to make adjustments to cope with new realities and challenges, and ensure that its response to the changed circumstance does not put ASEAN squarely on one side or another. It is a difficult situation for ASEAN where two of its most important partners are having serious problems with each other, and the end-game is still not apparent.

ASEAN will also have to address the free and open Indo-Pacific concept now that the U.S. Department of Defense has made clear its Indo-Pacific strategy through a report released during the Shangri-La Dialogue. This is by far the most detailed U.S. iteration of the Indo-Pacific concept from the strategic and defense perspectives. The report served to confirm that the term “Asia-Pacific” will no longer be used in the U.S. lexicon and that the Indo-Pacific defines the U.S. strategic theater.

The United States sees its free and open Indo-Pacific strategy as further empowering the notion of ASEAN centrality in the regional security architecture. It is not clear what empowering ASEAN centrality means although it implies an expectation that ASEAN will factor the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy into its concept of ASEAN centrality. The report also noted that the United States respects ASEAN’s consensus based decision-making model but adding “we believe that the more ASEAN speaks with one voice, the more it is able to maintain a region free from coercion,” reflecting a concern over ASEAN unity. ASEAN will have to decide what this Indo-Pacific strategy would mean for the notion of ASEAN centrality and its impact on the hitherto ASEAN-led regional architecture. China has made clear in ASEAN-led forums its preference for the status quo, meaning a focus on the Asia-Pacific with East Asia as the core as opposed to a wider Indo-Pacific focus.

ASEAN has so far has not formulated a clear position on the Indo-Pacific concept. Now is as good a time as any, under Thailand’s chairmanship, for ASEAN to decide on how it can position itself so that the ASEAN-led regional architecture remains the best option for regional stability and security and is not diluted by an expanded regional framework encompassing a wider area. It can be expected that China’s “friends” in ASEAN would work to ensure that China’s concerns would be factored into any discussion that ASEAN would have on the subject.

ASEAN’s primary focus must be to ensure that its development and integration goals continue unabated, maintain its commitment to rules and norms based on international law, and continue to speak out to preserve free trade, multilateralism, and open markets. Singapore’s minister for trade recently spoke of the need for ASEAN to remain an open platform and forge partnerships with as many countries and economic blocs as possible.

ASEAN leaders will have a lot on their plates to discuss to come to a common understanding on the economic and security challenges facing the region and the steps that ASEAN has to take to meet these challenges. ASEAN unity is key in this regard.

Hirubalan V. P. is a former Singaporean diplomat who served in Jakarta, Brunei, Saudi Arabia, and the Philippines. He last served as Deputy Secretary General in the ASEAN Secretariat, in charge of the Political and Security Department before retiring from public service. The views expressed here are his own.