The days unfold at a leisurely pace in Tonga, a South Pacific archipelago with no traffic lights or fast-food chains. Snuffling pigs roam dusty roads that wind through villages dotted with churches.

Yet even in this far-flung island kingdom there are signs that a battle for power and influence is heating up among much larger nations — and Tonga may end up paying the price.

In the capital, Nuku’alofa, government officials work in a shiny new office block — an $11 million gift from China that is rivaled in grandeur only by China’s imposing new embassy complex.

Dozens of Tongan bureaucrats take all-expenses-paid training trips to Beijing each year, and China has laid out millions of dollars to bring 107 Tongan athletes and coaches to a training camp in China’s Sichuan province ahead of this month’s Pacific Games in Samoa.

“The best facilities. The gym, the track, and a lot of equipment we don’t have here in Tonga,” said Tevita Fauonuku, the country’s head athletic coach. “The accommodation: lovely, beautiful. And the meals. Not only that, but China gave each and everyone some money. A per diem.”

China also offered low-interest loans after pro-democracy rioters destroyed much of downtown Nuku’alofa in 2006, and analysts say those loans could prove Tonga’s undoing. The country of 106,000 people owes some $108 million to China’s Export-Import bank, equivalent to about 25% of GDP.

The U.S. ambassador to Australia, Arthur Culvahouse Jr., calls China’s lending in the Pacific “payday loan diplomacy.”

“The money looks attractive and easy upfront, but you better read the fine print,” he said.

China’s ambassador to Tonga, Wang Baodong, said China was the only country willing to step up to help Tonga during its time of need.

Graeme Smith, a specialist in Chinese investment in the Pacific, is not convinced China tried to trap Tonga in debt, saying its own financial mismanagement is as much to blame.

Nonetheless, he said it’s worrying that the nation of 171 islands, already vulnerable to costly natural disasters, has little ability to repay.

Why is China pouring money into Tonga?

Teisina Fuko, a 69-year-old former parliament member, suspects China finds his country’s location useful.

“I think Tonga is maybe a window to the Western side,” he said. “Because it’s easy to get here and look into New Zealand, Australia.”

“It’s a steppingstone,” he said.

For decades, the South Pacific was considered the somewhat sleepy backyard of Australia, New Zealand and the United States. Now, as China exerts increasing influence, Western allies are responding.

Experts say there hasn’t been this level of geopolitical competition in the region since the U.S. and Japan were bombing each other’s occupied atolls.

“We haven’t seen anything like this since World War II,” said Smith, a research fellow at Australian National University.

After Cyclone Gita destroyed Tonga’s historic Parliament House last year, the government first suggested China might like to pay to rebuild it. Then Australia and New Zealand stepped in and are now considering jointly funding the project.

Elsewhere in the region, Australia is redeveloping a Papua New Guinea naval base while New Zealand has announced it will spend an extra $500 million on overseas aid over four years, with most of it directed at South Pacific nations.

Rory Medcalf, the head of the National Security College at Australian National University, said the area could provide a security bridgehead for China’s navy, which currently must sail through the U.S.-friendly islands of Japan, Taiwan, and the Philippines to get to the Pacific.

Other possible explanations, Medcalf said, include the region’s fisheries, seabed minerals, and other natural resources, as well as China’s ongoing effort to lure away the few remaining countries that recognize Taiwan instead of China — several of them Pacific island nations.

“It’s not entirely clear what China wants in the South Pacific,” Medcalf said. “It’s just clear that China is becoming very active and making its presence felt.”

China has poured about $1.5 billion in aid and low-interest loans into the South Pacific since 2011, putting it behind only Australia, according to an analysis by Australian think-tank the Lowy Institute. And that figure rises to over $6 billion when future commitments are included.

China’s use of loans and aid to gain influence in developing nations worldwide is nothing new, as illustrated by Chinese-financed projects from Africa to Latin America and the Asian subcontinent.

Some worry that these can become debt traps when nations can’t repay. In Sri Lanka, for example, the government was forced to hand over control of its Hambantota port as it struggles to repay loans it got from China to build the facility — a move that has given Beijing a strategic foothold within hundreds of miles of rival India.

Wang said China has only benevolent intentions in Tonga and no hidden agenda. “Some people in the West are being over-sensitive and too suspicious,” he said. “No need.”

It’s not just money flowing in from China. Chinese immigrants began arriving in the 1990s when Tonga started selling passports.

The passports, which went for about $10,000 each, were aimed at attracting wealthy Hong Kong residents hedging their bets ahead of the former British colony’s return to China in 1997. Instead, they were snapped up by rural Chinese looking for a better life — and who now compete with native Tongans for scarce jobs.

Chinese immigrants already run most of the dozens of hole-in-the-wall groceries dotting the islands, selling cheap imports like potato chips and canned meat. And Tongans worry they are now expanding into farming and construction.

Most Tongans live a subsistence existence in a nation where the king is revered and people take Christianity so seriously that working on Sundays is, with few exceptions, banned under the constitution. The economy relies on foreign aid and cash sent home by Tongans working abroad.

And the Chinese loans haven’t changed that because the money went to Chinese-run projects, Fuko said.

“They brought the money, they brought the workers, they brought the building materials,” he said. “Maybe a few Tongans pulled wheelbarrows.”

Wang acknowledged the criticism that Chinese immigrants run many businesses but said Tonga’s leaders recognize the contribution they make and have even called on Tongans to learn from their hard-work ethic.

Tonga never benefited from the passport money, either. A former financial adviser to the government, American Jesse Bogdonoff, helped place about $26 million into speculative investments and almost all of it evaporated.

The real threat to Tonga’s future may lie in its crippling loans from China.

In December 2017, the International Monetary Fund increased Tonga’s debt distress rating from moderate to high risk, citing its vulnerability to natural disasters and noting that the large upcoming loan repayments to China would reduce Tonga’s foreign exchange reserves, double its debt-servicing costs, and could force the country to borrow yet more money.

Repayments were due to start last year, and panic crept in.

In August, Prime Minister ‘Akilisi Pohiva called on other Pacific nations to join forces to demand debt relief, warning that China could snatch away buildings and other assets. But he reversed his position days later, saying Tonga was “exceedingly grateful” for China’s help.

Within months Tonga announced it had been given a reprieve and didn’t need to start repayments for another five years.

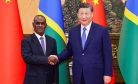

Tonga also said it was joining China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the trillion-dollar global investment and lending program that is a signature policy of President Xi Jinping.

Tongan officials don’t seem eager to discuss the relationship with China. The prime minister withdrew from an interview with The Associated Press because of an illness, while Finance Minister Pohiva Tu’i’onetoa cancelled at the last minute due to “something urgent.” The chief secretary to the prime minister’s office, Edgar Cocker, agreed to meet but then quickly asked a reporter to leave, saying he wasn’t authorized to speak for the government.

Cocker said all questions about China’s loans and aid should be directed to Chinese officials.

Wang said there was no link between Tonga getting a break on its loans and joining the Belt and Road Initiative. He said Tonga had raised concerns about the loan, and China was willing to help.

Tonga’s immediate financial crisis has been averted, but Fuko thinks the loans have given China the upper hand.

“I don’t know how we are going to pay that back,” the former lawmaker said.

An unintended consequence of Tonga’s China loans could be a reduction in foreign investment and withering of the revenues needed to pay them back.

Take the Scenic Hotel. One of the few large hotels on the main island of Tongatapu, it abruptly closed its doors in March in a setback to the key tourism industry.

Brendan Taylor, managing director of the New Zealand-based Scenic Hotel Group, said one problem was the new Foreign Exchange Control Act Tonga introduced last year.

Designed to keep money in the country and protect its currency during financial emergencies, it was enacted as Tonga prepared to begin making the Chinese loan repayments.

“The issue you have got in Tonga is that no overseas companies are keen to go in,” Taylor said. “They’ve cut out investors.”

He said the hotel got a large insurance payout after it was hit by Cyclone Gita. But the new law created legal hurdles to move money out of Tonga to pay New Zealand suppliers for repairs and so the payout languished in a Tongan trust account, he said.

Tonga-based lawyer Ralph Stephenson said that while the law isn’t being enforced, it’s still spooking investors.

“The penalties for breaching the act are Draconian, in terms of fines that can be imposed, and also in so far as the act actually affords the courts the power to forfeit property,” he said.

Wang said any suggestion that China might be engaged in a Pacific power struggle with the West or using Tonga to keep tabs or even spy on New Zealand and Australia is nonsense.

“Tonga is a small country. It’s almost impossible to hide any secret,” Wang said. “For some of our Western friends, personally, I think they should be confident in their relations and influence in this region.”

If China sees any strategic importance to Tonga, it was the country’s recognition that Taiwan is part of China, he said. Tonga switched from recognizing Taiwan and established formal diplomatic relations with Beijing in 1998.

China’s economic success has allowed it to build new embassies around the world and too much shouldn’t be read into the size of its new embassy in Tonga, Wang said.

He said that over the past 20 years, diplomatic relations between China and Tonga have widened to include infrastructure, trade, education, and sports. He doesn’t see it as a case of larger countries jockeying for influence.

“I don’t think so,” he said. “Just whoever is able to provide assistance for the goodness of the Tongan people.”

But for Ola Koloi, who runs a tourist lodge, China’s footprint is too pervasive, influencing what she can buy since so many goods for sale come from China.

She said the China loans should worry every Tongan.

“I feel like I’ll be Chinese soon,” she said.

By Nick Perry for The Associated Press.