NEW DELHI / KARACHI / JAIPUR / MULTAN — In a slum on the outer periphery of Gurgaon, far away from all the trappings of luxury, lives Pooja — a young bright-eyed girl who dreams of a better life. Like many her age, Pooja is not privileged to receive education at a private school. The 15-year-old hails from a family of poor migrants who have never witnessed the miracles of education.

Pooja is enrolled at a small makeshift school with a frail structure and temporary ceiling that shivers when strong winds blow.

“I want to become a teacher,” she says in a brittle voice.

Her face glows with joy every time she talks about her school. Pooja’s school is no ordinary school. She receives education at a mobile school.

Across the Radcliffe line in Maripur, Karachi, approximately, 1,000 kilometers away from Pooja, lives Roshail Atta Mahommad. The 17-year-old’s life has an uncanny resemblance to Pooja’s situation. She too has defied all social and cultural odds for education. Roshail, like Pooja, wants to become a teacher and contribute to her community’s well-being.

Even after 70 years of independence, millions of children in India and Pakistan are deprived of education. Both countries are confronting the perils of their failure to educate their citizens, notably the poor. Pooja and Roshail are among the deprived generation who were left out of the state-run education system in their respective countries.

The two may be divided by the border, but they are united by the failure of their governments to fulfill their basic fundamental right to education.

Children study in an informal school in Jaipur. The classrooms don’t have benches in order to accommodate more children.

For decades governments in India have made tall symbolic promises about improving the state of education in India. They’ve conceived policies and plans that have been nothing more than toothless paper tigers. The Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP)-led government in Delhi has slashed education spending by nearly 50 percent in the last 4 years. Such misplaced national priorities deprive many like Pooja of education — a promised universal birthright.

Echoes of similar hollow political promises are also responsible for the burgeoning education crisis in Pakistan.

The two nuclear rivals inherited innumerable common issues. Education is one of them. In many ways their approaches to the issue have been similar too. The two arch-rivals have identical laws that ensure free and compulsory education but little has been done to implement them. The Right to Education Act, 2009 (RTE) in India recognizes free and compulsory education for children between the age of 6 and 14, under Article 21a of the Indian Constitution. Similarly, in Pakistan Article 25-A of the constitution guarantees the right to free education to all children between the ages of 5 to 16. The right to education was enacted, in both countries, with the idea to improve the state of education, but it has been haunted by procedural inefficiencies.

According to Academy of Educational Planning and Management (AEPAM) report, an estimated 22.8 million children are out of school between 5 and 16 in Pakistan and those who do go to school haven’t even achieved the basic learning levels.

Students prepare to go back home after a productive day at their makeshift school, the Tikri Education Center outside Karachi.

The Heroes

When governments fail to deliver fundamental rights, people rise to help their communities. Sandeep Rajput in India and Gamwar Baloch in Pakistan are two such heroes.

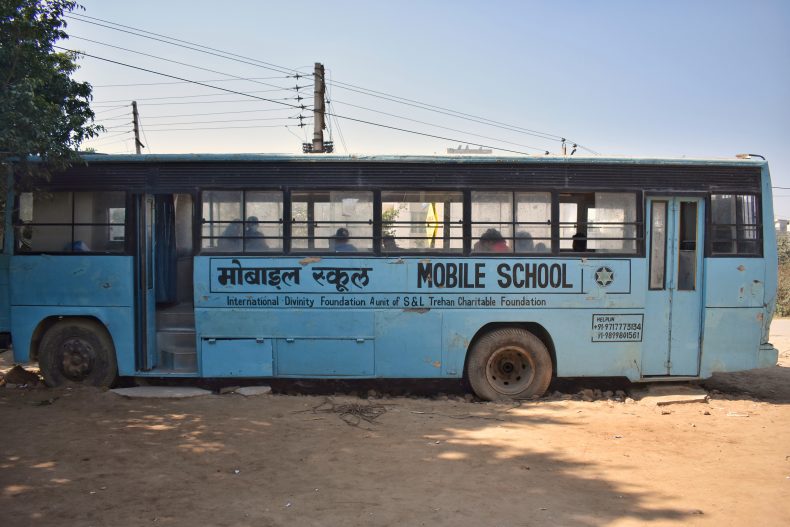

The mobile school, run by Rajput, 41, is a free education facility on wheels. Rajput is known for chasing illiteracy in decrepit areas of Gurgaon in an old public bus. The decommissioned vehicle, once used by commuters, is now reconfigured to serve as a classroom on wheels. It is equipped with small tables and everything else a teacher might need to run a classroom. Rajput’s school on wheels, as it’s commonly known, is also recognized by the National Institute of Open Schooling (NIOS).

This converted bus acts as a mobile classroom for children.

Rajput blames the government for failing to support free education. “The school in this area was visited by a local commissioner once who made tall promises but we’re still waiting for him to deliver upon them.”

With limited resources, Rajput claims that the school is self-sufficient and runs with the help of independent donors or funds provided by corporate organizations.

“So what if they can’t go to a school, we can ensure that a school reaches their doorsteps and that’s where our mobile school plays a crucial role,” Rajput says passionately.

A busy day in class for Mobile School students in Gurgaon.

Like Rajput, Pakistan too has a warrior, who fights against an unfair educational system. In 2013, Gamwar Baloch, 21, established a makeshift school named “Tikri Education Center.” The school provides free education to the deprived students in Maripur — a neighborhood of Kiamari town in Pakistan’s southern port city of Karachi. Baloch helps those who have been neglected by the state and are at the very bottom of Pakistan’s social ladder.

Infrastructure is weak at her school. There are no benches and there are no desks. All of her 300 students are seated on the floor during class hours. Roshail was one of those students who survived the challenges and made it through. She now teaches along with Baloch, who is supported by a staff of three permanent teachers at the school.

“I don’t want girls from my community to suffer or struggle for education,” says Roshail, who has joined Baloch’s small army of heroes fighting the war against illiteracy in Maripur.

Students at Tikri Education Center.

Despite all the political promises of promoting equality, education has become a crucial marker of inequality in both India and Pakistan. In Rajasthan, education remains a distant dream for Pooja and many like her.

“I want to pursue so many things but that is not possible,” she says with a tinge of hopelessness in her voice.

The Struggle

In her hostel-cum-school building, Shivani has found a quiet corner for herself to study in a big shared room. She has her medical entrance examination approaching in 15 days. Her days are spent surrounded by medical books piled on top of each other. She is not an ordinary girl and her struggle sets her apart from the 200,000 other medical aspirants. The 19-year-old recollects childhood memories of her father abandoning her after her mother’s death, and a careless family structure. Her past hasn’t deterred her spirits.

Shivani was enrolled in a makeshift school in Jaipur, Rajasthan, when she was four years old. After several years of teaching students in open spaces, parks, under makeshift tents, the school finally moved to a three-story building in 2008 where she studies and resides along with many children who have been deprived of education by an unfair state-run system. The school is run by 66-year-old Vimla Kumawat, whom the children fondly refer to as “Dadi.” The school has been named Sewa Bharati Bal Vidyalaya after the organization Sewa Bharati, which is one of the major donors of the school.

Children rush back home after a busy day at their informal school in Jaipur.

The stories of struggle by children of marginalized communities in India and Pakistan have an uncanny resemblance. Away from the deserts of Rajasthan, India, along the banks of Chenab river, resides Mohammed Siddiq, who is the founder of Ujala foundation — a temporary school for underprivileged students in Multan. One such student is Iqra whose illiterate parents dreamed of educating their daughter. Owing to financial constraints, they couldn’t provide for her education. However, Siddiq’s makeshift school ensured that children like Iqra do not remain deprived of education.

Now she vows to help children who belong to the bottom of Multan’s multilayered society where Saddiq’s makeshift school is their only hope and individuals like her are saviors.

Initiatives by local superheroes like Vimla Kumawat and Mohammed Siddiq play a pivotal role in the lives of children who are struggling to acquire good education — a fundamental and promised constitutional right in Pakistan and India.

Shivani’s journey from a life of ignominy as a ragpicker to a medical aspirant studying in a premier coaching institute of the city is a journey from the margins to the mainstream. However, the community in which she was born, Valmiki (Dalit), is still hesitant to allow girls to study.

“If Shivani clears her medical entrance, it will be a beacon of hope for the children and motivate them to push their boundaries,” remarks Kumawat, her eyes carrying a hope for a better future.

To win Shivani’s admission in a medical coaching program, Kumawat waited two days at the reception of the coaching institute in the hope that she would get a fee waiver. The journey hasn’t entirely been easy for Kumawat. Coping with the lack of money, she has had a tough time managing the needs and expenses.

“There have been days when I couldn’t even provide the students with notebooks but I’ve never given up,” says Kumawat with her usual politeness and unwavering resolve to fight the battle against an unfair education system in India.

In this informal school in Jaipur, close to 30 students are crammed in a 10×10 room.

Siddiq faces a similar situation in Pakistan. He does not receive any support from any organization, “I believe that education of underprivileged children is the society’s responsibility,” says Siddiq.

Vimla Kumawat’s school in Jaipur’s Mahesh Nagar has another branch on the outskirts of the pink city, in Baksawala. The area is inhabited by people from the Dalit community, who live in slums. Their homes are located along the main road and the nearest government school is one-and-half kilometers away.

“Parents are reluctant to send their children to government school because they have to cover this distance by foot,” says Ashok, the upkeeper of Baksawala makeshift school. The school at Baksawala has no permanent structure. Children study under a tree or out in the open, fighting the high temperatures in Rajasthan.

Ashok runs the school with two more volunteers. They found an abandoned building for children to study. The children are crammed in tiny congested rooms with little space for movement. A small window and the classroom door act as the only source of natural light and air.

When it comes to the deficiencies in the education system, K. B. Kothari, managing trustee of Pratham Education Foundation, a charitable trust that works toward the provision of quality education to underprivileged children in India, puts the blames squarely on the political leadership in the country.

“The major responsibility for this [failure] must be attributed to political leadership at all levels,” Kothari says.

Nevertheless, both India and Pakistan have heroes like Kumawat and Siddiq, and warriors like Shivani and Iqra. They stand tall against all odds and against all failures.

“I used to roam around garbage for rag-picking,” Shivani recalls without batting an eye. “I dream of becoming a doctor now,” she says, with a visible glow on her face.

This story is a collaboration by journalism students of AJK MCRC, Jamia Millia Islamia (India) and the Center for Excellence in Journalism (Pakistan). The team members include Madhuraj, Sarah Khan, Babrah Muskan Naikoo, and Tehseen Abbas.