In September 2018, Ghulam Abas, coach of Maiwand wrestling club in the Dasht-e-Barchi neighborhood of Kabul, was training athletes when an Islamic State suicide bomber opened fire on the guard. As he rushed to open the emergency door, the bomb denoted in the club, which was packed with athletes. Abas lost his left arm but survived; 20 of his young trainees were killed and 70 others wounded.

In July 2019, Afghanistan’s spy agency, the National Directorate of Security (NDS), arrested four suspects on charges of designing the attack on the wrestling club. The suspects were not from Afghanistan’s rural areas — they were lecturers and students at the country’s largest university: Kabul University.

“We do not expect students of Kabul University to target our club,” said Abas. “Students of Kabul University are expected to build a bright future for the country and run the country tomorrow.”

Ghulam Abas, the 51-year-old coach of a wrestling club in Kabul, lost his arm in a terrorist attack allegedly masterminded by Kabul University Students. Photo by Ezzatullah Mehrdad.

Amid raging insurgency in the country, people pin their hope on the partially U.S.-funded Kabul University to educate a liberal and open-minded generation. But the newly emerged Islamic State (IS) in Afghanistan has infiltrated the country’s oldest university to recruit fighters from among students, an issue that rings alarm bells about the expansion of the Islamic State amid a possible peace deal between the United States and the Taliban.

The Islamic State, or Daesh, has recruited “many students” from Kabul University and sent them to its stronghold in eastern Nangarhar province for training, said one of the students who was arrested in a recorded confession released by NDS.

The NDS arrested Mubasher Muslimyar, an Islamic law lecturer at Kabul University, two Kabul University graduates, and one relative of Muslimyar in July. Earlier, the spy agency had detained Zaher Dai and Maroof Rasikh, two Islamic law lecturers at Kabul University, on charge of recruiting students for the Islamic State.

Ahmad Tariq, one of the detained students, confessed to NDS investigators that Muslimyar initially attempted to convert students to Salafism, a fundamentalist branch of Sunni Islam, before encouraging them to join Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), the Afghanistan-based branch of the terrorist group.

The spy agency blamed Tariq and Ahmad Farouq, two university graduates, for attacks on Maiwand Wrestling club, a bus carrying government employees and Hamid Karzai International Airport in the Afghan capital, Kabul.

“Many of the divided and unhappy Taliban commanders left the Taliban group following division over the group leadership after Mullah Omar, emir of the group, died in 2013,” said Khadem Hussain Karimi, author of a book about the Islamic State and Afghanistan’s Shiites. The “Pakistan army pushed extremist groups out of its soil” and together they formed ISKP in 2014.

The United States and the Afghan government were unable to eliminate affiliates of ISKP and its suicide bombers carried out deadly attacks across the country. ISKP still controls a swath of eastern and northeastern Afghanistan and the group is expanding its footprint.

“The first priority of [ISKP] was of course establishing a sufficiently solid presence in pockets of Khorasan, on which to start building a more sophisticated structure and from where to spread,” wrote Antonio Giustozzi in his book The Islamic State in Khorasan. The group was “a largely alien entity that needs to somehow disembark and gradually establish roots and organize itself.”

To expand its reach, the Islamic State targeted Afghan universities across the country, including Kabul University as well as Nangarhar University in eastern Afghanistan. The academic institutions proved to be vulnerable for exploitation by the Islamic State.

Ramin Kamangar, a researcher based in Kabul, said that historically many extremist groups had deep roots in Afghan society. The academic curriculum was designed in such a way that every group could manipulate academic textbooks, including Sharia law textbooks, which are mandatory courses for every faculty across the country.

“The textbooks of Islamic law are not academic,” Kamangar said. “They present that Islam is the best religion and speak in the form of ideological black and white.”

Kamangar conducted research about religious radicalization in Afghanistan’s higher education system with the Afghan Institute for Strategic Studies. The research found that half of 373 students surveyed at three major Afghan universities — Kabul University, Herat University, and Nangarhar University — supported an Islamic Emirate or Caliphate as political system.

About 20 percent of the students were opposed to secularism or living alongside religious groups other than their own. Three-quarters of the students supported the idea of proselytizing Islam globally.

Kamangar believes that the educational system does not encourage critical thinking and failed to produce graduates who were able to think and understand their surroundings independently — and therefore, they were vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups, particularly the Islamic State.

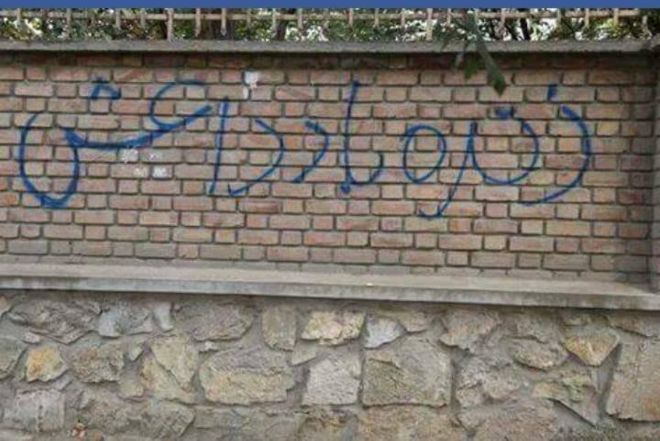

Graffiti written on the wall of Kabul University reads “Long Live Daesh (Islamic State).” Photo courtesy of social media.

While the U.S.-Taliban peace talks make progress and U.S. President Donald Trump impatiently waits for an exit from Afghanistan, the Islamic State enjoys space to recruit Afghan youths to wage a new episode of war in the country and in the region.

In the eighth round of U.S. negotiations with the Taliban group in Doha, Qatar, U.S. special envoy Khalilzad said that the two sides made “excellent progress” over a deal with the Taliban. Their teams are reportedly working on details and implementation of the deal.

The Islamic State threatens to complicate any peace deal. ISKP “also had a strategic aim of ultimately replacing the Taliban, TTP [Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan] and other insurgent groups in Khorasan, establishing its own monopoly as it has been trying to do in Syria and Iraq,” wrote Guistozzi. He quoted an Islamic State fighter as saying: “If Taliban made peace with the Kabul government, maybe a lot of Taliban would join us.”

Razaq Modaber, a 23-year old, who graduated from Kabul University last year, says Islamist extremist groups have the upper hand everywhere, including Kabul University. The Islamic State, particularly, could have rooted deeply among students.

“One year ago, they [the suspects detained by NDS] were students of economy faculty of Kabul University,” said Modaber. “It is hard to trust my classmates and other students.”

One of many students who was recruited by the Islamic State was 23-year-old Mohammad Rafi. In 2015, Wali Mohammad Darwazi, father of Rafi, searched for his son after Rafi vanished with several former classmates from Kabul University.

Darwazi was able to connect by phone with one of his son’s classmates, who was in Syria, fighting for the Islamic State. “Rafi has been martyred,” he told Darwazi, saying that Rafi and other Afghans had been killed in a U.S. coalition airstrike near Baiji, Iraq, in May 2015.

According to Rafi’s relatives, the computer science student and soccer lover enrolled in an Islamic culture course at Kabul University and began to grow more religious. Rafi attended mosques in two upscale neighborhoods of Kabul and grew a beard. His parents believed that some Islamic lecturers at Kabul University identified Rafi as a potential recruit and radicalized him in sessions after classes or after mosque prayers.

“He was influenced by Afghans who studied in Arab countries,” Darwazi told the Washington Post in 2015. “They misused his innocence.”

Ezzatullah Mehrdad is a journalist based in Kabul, Afghanistan. He tweets @EzzatMehrdad.