In September 2019, the Solomon Islands switched its diplomatic recognition from the Republic of China (ROC, hereinafter referred to as Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China (PRC, hereinafter referred to as China). This is a blow to Taiwan as the Solomon Islands was the largest among the six Pacific Island countries that maintained official relations with Taiwan before the switch. Now the number is reduced to four as Kiribati followed the Solomon Islands in switching. While much of the debate is on the potential domino effect, a careful reading of the report produced by the Solomon Islands parliamentary bi-partisan task force, a key player appointed by Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare in June to review the country’s relations with China and Taiwan, and the statement by Sogavare on the switch, reveals a lot about local perceptions of China’s rise and changing geopolitics in the region.

The task force consisted of nine members, including seven parliamentarians (three each from the government and opposition and one independent member) and two secretariat staff from the Office of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. After consulting with officials and stakeholders from countries including Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Tonga, Vanuatu, China and Taiwan (denied by Taiwan), the team recommended that the Solomon Islands sever diplomatic ties with Taiwan and normalize relations with China no later than the celebration of the PRC’s 70th anniversary on October 1, 2019, which was adopted by Honiara. Their views were strikingly direct:

First, Taiwan is unable to offer enough assistance as the Solomon Islands expects. The task force argued that “the 36 years of diplomatic relation clearly illustrated that Taiwan will not do anything substantial in infrastructure development to support the economic growth of Solomon Islands…Solomon Islands should not bet on Taiwan’s assistance.” The main tension is over aid in infrastructure development. This matters to the Solomon Islands as poor infrastructure is regarded as the country’s biggest obstacle, severely hampering its development despite rich resources in minerals, forestry and fishery.

Over the 36 years between 1983 and 2019, Taiwan provided a total of$460 million in aid to the Solomon Islands. To garner support for diplomatic relations, a large proportion of Taiwanese aid went to the Rural Constituency Development Fund, which enjoys popularity among parliamentarians as its use is at their discretion, but invites broader criticism for breeding corruption. Taiwan also provided technical assistance to sectors such as agriculture and health in the Solomon Islands. However, the gap for infrastructure funding remains to be filled. Prime Minister Sogavare also complained that Taiwanese investors have shown less interest in investing in economic development than political interests in his country over the past 36 years.

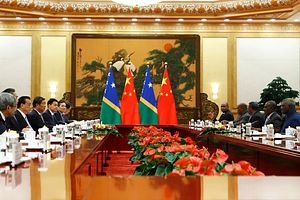

Second, China’s promises in trade, aid and investment appeal to the Solomon Islands government, especially in infrastructure. After meeting with senior Chinese diplomats and representatives of large Chinese enterprises operating in the Pacific such as China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation, China Harbour Engineering Corporation and Huawei, the task force concluded, “Solomon Islands stands to benefit a lot if it switches and normalize diplomatic relations with PRC.” Prime Minister Sogavare stated that “we believe that by establishing diplomatic tie with PRC can assist the country achieve some of its development aspirations.” China also assured the Solomon Islands that it would provide aid to fill the gap left by Taiwan’s departure in the transition period, including to take on the Solomon Islands students currently studying in Taiwan and fund the 2023 South Pacific Games stadium. In particular, the Solomon Islands government is attracted to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) which presently anchors China’s bilateral cooperation with the Pacific especially in infrastructure. The Solomon Islands signed up to the BRI during Sogavare’s visit to Beijing in October 2019, aligning the Chinese initiative with the Solomon Islands’ National Development Strategy 2016-2035. The task force had high hopes on the BRI, arguing that “This, China initiative, holds the only means to solve this national development issue [infrastructure constraint].”

The strong bilateral trade relationship between China and the Solomon Islands was also highlighted by the task force and Sogavare to support the switch. China is the Solomon Islands’ largest trading partner with a trade volume 14 times that of Taiwan. According to the World Bank, in 2017, the Solomon Islands exported $554.8 million worth of commodities, or two-thirds of its total exports, to China and 87 percent were wood products. Another factor mentioned by the task force is the strong people-to-people links underpinned by the Chinese diaspora (about 3,000) in the Solomon Islands who have been active in the local economy especially the retail sector. While contributing to local economies, some Chinese are resented by Solomon Islanders for briberies, selling cheap substandard products, violation of customs and inability to integrate with local communities. This makes them easy targets during social unrests such as the riot in 2006. In this context, establishing diplomatic relations with China might provide an opportunity for the Solomon Islands, in partnership with China, to regulate Chinese business activities in the Pacific country and strengthen law enforcement.

Third, in general the task force depicted a rosy picture of China-Pacific relations and the potential benefits for the Solomon Islands. However, it also cautioned briefly that the Solomon Islands needs to develop a policy of “strategic engagement” with China. The task force highlighted the importance for the Solomon Islands government to “manage” the new relations with China well, “set the mechanisms and framework in place, and have qualified professionals and expertise to manage these relations.” It also showed interest in learning from other Pacific Island countries such as Fiji and Vanuatu in dealing with China in a variety of ways: developing good relations with both Western powers and China; managing external debts and safeguarding local land ownership; and having laws and regulations (relating to investment, immigration, land and labor) in place to accommodate influx of Chinese aid and investment.

Fourth, the United States has substantial influence in the three associated states of Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau, but its influence in other Pacific Island countries is arguably constrained. The task force was critical of the United States for its focus on diplomatic and security issues rather than economic development in the Pacific including in the Solomon Islands. It claimed that the United States supported the Solomon Islands in reviewing its relations with China and Taiwan and “there may not be any backlash in the event we switch,” which proved to be wrong.

The U.S. government opposed the Solomon Islands’ switch to China, which was resented by Prime Minister Sogavare in his statement. This is probably why the task force added that “on the reaction from traditional donors as a result of the switch, there will be some impact on the country [Solomon Islands] and hence the need to review and enhance our engagement with our traditional donors.” A closer relationship with China may increase the bargaining power of the Solomon Islands in dealing with traditional powers, but will bring about more pressure from the latter.

The Solomon Islands and China will soon enter a honeymoon period. The two countries will open up embassies in Beijing and Honiara; Chinese aid will start to flow in. For the first time, the Solomon Islands is going to join the other nine Pacific Island states (including Kiribati) that recognize China in attending the third conference of the China-Pacific Islands Economic Development and Cooperation Forum in Apia on October 20-21, and benefit from new aid packages under the BRI framework.

In the long run, two main challenges are prominent. First, to manage the relations with China well, as the task force suggested, is easier said than done. The internal challenges in the Solomon Islands alone are enormous, such as weak institutional capacity and corruption, and will need to be managed while navigating the new relationship with China. Another challenge relates to the growing strategic competition between China and the United States in the Indo-Pacific region. Whether the Solomon Islands government is able to develop good relations with both of the two superpowers, again as the task force wished, is to be tested.

Dr. Denghua Zhang is a research fellow at Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs, Australian National University. His research focuses largely on Chinese foreign policy, foreign aid and China in the Pacific. Recently, he has published with journals such as The Pacific Review, Third World Quarterly, The Round Table and Asian Journal of Political Science.

The author would like to thank Dr. Transform Aqorau for his comments.