Between 1877 and 1879, Ulysses S. Grant helped inaugurate a new era of U.S. diplomacy by launching an extensive world tour. In particular, the tour helped solidify the U.S. diplomatic position in East Asia. Given that Grant’s career is in the midst of a major reconsideration, this tour deserves more attention as a key moment in the expansion of America’s diplomatic reach across East Asia, and the world.

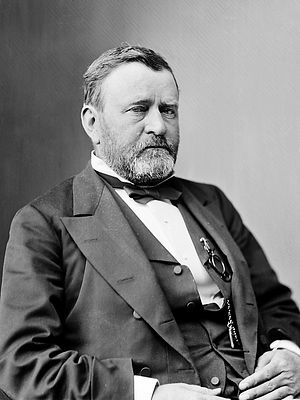

After completing his second term as president in 1877, Grant embarked on a world tour, one of the first efforts in post-presidential diplomacy. Grant had served as the commander of all Union armies during the Civil War, and was regarded as central military figure in the Union’s victory over the Confederacy. He then served two terms as president, the first person to successfully do so since Andrew Jackson. In short, Ulysses S. Grant was one of the most famous, most distinguished men in the world when he embarked on his 1877 tour.

Grant began his tour in Europe, where he visited most of the major national capitals and met with leaders such as Otto von Bismarck, Czar Alexander II, and Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. These visits helped mark the emergence of the United States as a major military and political power. Grant also visited the Middle East, becoming the first U.S. president to step foot into Jerusalem. However, the truly distinctive part of the tour came as Grant visited the Far East. Grant believed that the commercial future of the United States lay in East Asia, and that a series of meetings could help solidify America’s political position in the remaining independent states across the region.

Grant’s relatively enlightened attitudes on race carried over into foreign policy, and especially to colonialism. Although Grant apparently believed that the British presence in India was justified by good works, he harshly criticized existing European imperialism in the rest of Asia. Moreover, Grant’s role in ending slavery was generally understood and appreciated in Asia. Grant undoubtedly benefited from the halo effect of the Lincoln presidency, but his administration’s commitment to Reconstruction, along with his own military deeds during the Civil War, ensured a positive reception among non-white peoples across Asia. Huge crowds turned out to see Grant in China and Japan, and local leaders competed for his attention. In Japan, the Meiji Emperor broke protocol by shaking Grant’s hand directly.

Asian leaders took advantage of Grant’s presence to pursue their own goals. In Beijing, Prince Gong asked Grant to mediate one of the many iterations of the Ryukyu Islands dispute with Japan (detailed by James Holmes here). Japan agreed, leading to a reduction of tensions but no permanent resolution. The U.S. political system was not necessarily well understood in Asia, and the degree of Grant’s influence over American politics was unclear, to the extent that locals probably overestimated his authority. However, the trip came at a time when Grant was seriously contemplating the possibility of running for a third term. A third presidential term, especially after the world tour, would have given Grant nearly unprecedented experience in foreign policy. Alas, Grant lost the 1880 Republican nomination to James A. Garfield, who was assassinated some six months after assuming the presidency.

Grant financed the tour personally, with the periodic support of U.S. Navy vessels serving as transport for him and his entourage. The success of the tour, even though it did not lead to a third term, demonstrated the value of “celebrity” diplomacy to the United States government. It also helped carve out a diplomatic position for the United States in East Asia. U.S. foreign policy in the decades that followed cannot be laid solely at the feet of Grant, as other powerful forces were also at work, but he left an outsized if often unnoticed mark on the growth of U.S. global presence after the Civil War.