Rule of law matters for economic development, and protecting the sanctity of contracts and upholding human rights are both part and parcel of the rule of law. It seems odd to have to write an article asserting this point; but such are the times we are in. My target audience for this piece include all those fellow economists who seem to believe the Philippines can still pursue development even under a regime that fails to uphold the rule of law, and more specifically fails to protect human rights. According to some, “as long we protect the sanctity of contracts our economy will grow.” This is a false dichotomy, and an overly narrow and shallow understanding of the rule of law and institutions.

A holistic institutional environment that fails to protect human rights also fails to uphold contracts. The downward spiral involving failure to protect both human rights and contractual rights is something the Philippines has seen before — during the initially welcomed and later widely condemned rule of dictator Ferdinand Marcos in the 1970s and ‘80s. It probably bears reiterating even more recent evidence if people have forgotten.

Rule of Law and the Economy

In a recent opinion piece, “The case for CITIRA’s lowering the Corporate Income Tax,” Raul Fabella of the UP School of Economics very succinctly summed up the international evidence on factors boosting foreign direct investments (FDI). It is clear from the literature, however, that lowering the corporate income tax rate is not the main constraint the Philippines presently needs to address. Instead the focus should be on infrastructure, high power costs, red tape (also known as the lack of “ease of doing business”), and unstable (and often captured) regulatory regimes, as well as weak rule of law.

Presumably, some progress is being made on infrastructure and energy (notwithstanding severe delays). And in May 2018 President Rodrigo Duterte signed the anti-red tape law, which in turn created the Anti Red Tape Authority (ARTA) as part of other efforts to lessen red tape and increase efficiency in the public sector. Yet perhaps the area with the least progress — or even recent regression– is the rule of law.

Law and order underpins any well-functioning economy. In recent research, “law” refers to the sturdiness and impartiality of the legal system, while “order” refers to the widespread observance of the law. In canonical models of the market economy, upholding the rule of law, as well as respecting property rights and contractual rights, are some of the key ingredients for the efficient functioning of markets. An already large body of literature asserts that weak rule of law is associated with anaemic foreign investment flows.

For instance, in a recent international survey of over 300 major multinational corporations by the Economist Intelligence Unit, the rule of law was among the top three considerations in making FDI decisions, with almost 90 percent of respondents indicating it as “essential” or “very important.”

It is interesting to note here the recent brouhaha over the decision by water concessionaires Manila Water and Maynilad to waive the 10.8 billion Philippine peso payment from the Philippine government based on the recent arbitration ruling in Singapore. The arbitration tribunal decided the Philippine government should pay Manila Water P7.4 billion and Maynilad P3.4 billion, due to losses they incurred when they were prevented from raising water rates in the past.

As noted by at least one private sector official, the decision to waive the ruling was a direct result of Duterte’s public rant against the concessionaires. Regardless of how one assesses the tribunal decision, these extralegal maneuvers by the president sent the private sector into panic, with the Philippine stock market losing almost P130 billion (over $2.5 billion) during the week of Duterte’s rant. The entire episode was a potentially reputation-damaging precedent, casting a shadow over the sanctity of contracts and the rule of law in the Philippines.

Human Rights Matter

Sanctity of contracts is one thing, but what about human rights? There is now growing evidence that the importance of rule of law to economic development is not merely limited to its direct application to property rights. In particular, upholding human rights is critically important to boosting investments and development. Hence, this dramatically expands the canonical view of economic theory, which often only has a narrow emphasis on rule of law for contract enforcement.

Recent research on FDI inflows uncovered evidence that human rights violations may provide a highly negative signal for foreign investors. In a panel data analysis of 165 countries during the period 1977–2013, Krishna Chaitanya Vadlamannati et al find evidence that condemnations by the UN Human Rights Commission and Council tend to diminish FDI inflows. The results suggest that “countries condemned by the UNHRCC are associated with a roughly 49% decline in FDI inflows.”

The authors further note: “These results suggest that shaming by the UNHRCC is a major driver of the negative effects on FDI […] possibly because of the high visibility of condemnations by an international body like the UN and the connected harsh pressure of resolutions on business reputation (bottleneck effect) as well as effects from isolation of the host county in the international community (outcast effect).” Clearly, condemnation on human rights violations could create knock-on effects in other areas, notably trade and investment flows, security partnerships, and perhaps even development assistance.

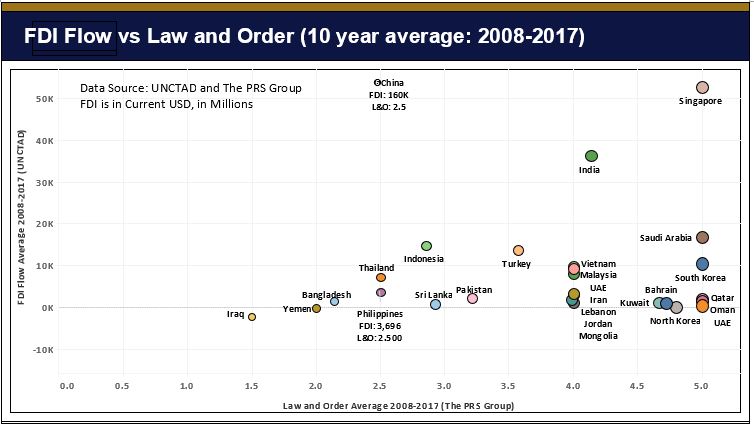

Both conceptually and in practice, it is difficult to imagine how one can “cherry pick” the development of institutions to produce the “rule of law.” Indeed, countries with generally poor human rights records often also have generally weak institutions. And as illustrated by a simple cross plot of FDI and law and order indicators for Asian economies in Figure 1, weak institutions and sub-par investment performance often go hand-in-hand.

Source: Ateneo Policy Center.

Scanning data on Asian economies, only China, India and Singapore tend to buck the trend, significantly outperforming peers at their level of law and order. (Law and order here is as defined previously: The “law” sub-component assesses the strength and impartiality of the legal system, and the “order” sub-component assesses popular observance of the law.) It is possible that these other countries possess other factors that also attract investments — such as population size for China and India, and strong governance and human capital for tiny Singapore. In no way do these facts weaken the economic argument for strengthening the rule of law, particularly for countries like the Philippines.

The argument here by institutions scholars is that institutions reinforce each other and are able to produce end results like “sustained and inclusive development” only because the entire architecture of institutions provides the stable platform to produce such results. Put simply, in a democratic setting such as in the Philippines, it is difficult to imagine citizens holding their leaders accountable when they must continuously depend on “patrons” for assistance with education, health, social protection, and other wants and needs, in an environment meanwhile that lacks many public goods and services. Disempowerment of citizens is also palpable under a judicial system that fails to uphold human rights much more effectively. How much more so if citizens are worried for their very safety and fear the state and their leaders.

In economic development discussions, the strength and independence of the judiciary is often left out of conversations as if one can operate a strong sustained economy with inclusive growth without a functioning, efficient, and trustworthy judiciary. Again, this is a false dichotomy. A professional and independent judiciary that can uphold human rights is likely the same one that stands to uphold the sanctity of contracts most effectively.

Poor Quality Institutions, Poor Quality Investments

As a final note, some analysts and media have been flagging anemic investment flows into the Philippines in November 2018, July 2019, and most recently in December 2019. Various factors may be behind this — including domestic and international reasons — and adding more concerns over the Philippines’ rule of law does not help. And an additional point here — even if investment flows held steady, it is critically important to start monitoring not simply the levels of investment, but also their nature. The problems attached to investments into Chinese POGOs (Philippine Online Gambling Operations) further emphasize that the net benefits from certain types of investments are weaker than others. POGOS don’t create many jobs; they are now increasingly associated with crime (e.g. kidnapping, prostitution, and drugs); and they, as yet, do not contribute significantly to tax revenues.

On the other hand, in Tanauan, Batangas, a world-class export zone managed by the Lopez Group of companies is home to investments like Murata Electronics (from Japan) and Collins Aerospace (from the United States). Murata manufactures several million ceramic microchips every day, which end up in regional supply chains for making state-of-the-art smart phones and television sets. Collins Aerospace manufactures aircraft cabin interior products, including cabin seating, lighting, oxygen systems, food and beverage preparation and storage equipment, galleys, and lavatories. These are the types of manufacturing-related investments that not only create many jobs, but they also provide important opportunities to break into major export markets (fueling growth and expansion) and enable rapid technology catch-up. Collins has begun to attract many Filipino engineers previously working abroad to repatriate and apply their skills to the company’s manufacturing designs. The next time you board a Boeing 737 or an Airbus 350, note that parts of these aircraft are now proudly made in the Philippines, and perhaps more importantly, designed by Filipino engineers.

One key reason we emphasize the importance of investment type here is that, more likely, the most development-friendly investments — i.e. job creating, technology transferring, export market opening, sustainability respecting FDI — are also likely much more sensitive to the rule of law environment. These types of investments typically come from countries with relatively stronger institutions for good governance. Mining investors from Canada, for instance, are bringing stronger community-partnerships experience due to the institutions they built to regulate mining activities in their home country — and they are pushing for more transparency and citizens’ oversight toward sustainable mining in the Philippines, in close partnership with the Philippine Chamber of Mines and different stakeholders. Moreover, investors from industrial countries with anti-corruption laws and anti-bribery protocols are compelled by their countries’ laws and policies to eschew corruption. These characteristics make them allies for domestic stakeholders pushing for good governance and greater freedom of information.

On the other hand, not all investors (and their investments) imply such benefits. It is well known that there are rising concerns over investments from countries that have much weaker institutions. Much has been written about China’s “corrosive capital,” which a growing number of analysts see as a threat to fragile democracies. In Latin America, analysts have already begun to question whether China is a partner or a predator. In the Philippines, it remains to be seen whether and to what extent Chinese investments will shed the initial negative press generated by POGOs.

Many of these nuances are unappreciated, as the media and the less informed typically just look at headline FDI figures. And yet higher quality investments matter critically to the nation’s development goals. And these types of investments often come from countries with strong rule of law and high-quality institutions — conditions that make them more sensitive to these same investment environment factors in the countries where they invest.

Restoring Balance

Perhaps Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson capture it best in their new book The Narrow Corridor. They emphasize the tricky balance between despotism and anarchy, with many developing countries trying to navigate the narrow pathway in between the two extremes. In many cases, society needs to catch up with an ever growing and increasingly powerful state and elite — often to assert their rights and provide the necessary checks and balances to keep their country on a balanced development path. That is only possible if the rule of law is strong, and if it includes not simply upholding contracts, but perhaps even more importantly, respect for human rights.

Ronald U. Mendoza, Ph.D., is Dean and Professor of Economics at the Ateneo School of Government, Ateneo de Manila University, the Philippines.