The killing of Qassem Soleimani, the head of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) Quds Force Unit, capped off a set of rising tensions in U.S.-Iran relations — a trend that Southeast Asian states have not been immune to. A reminder of that fact came earlier this week with respect to Malaysia, an influential and active Muslim-majority country, when a new round of hype surfaced regarding a reported ship seizure by Iran involving Malaysians. The reports were subsequently denied by Malaysia’s foreign ministry just ahead of Soleimani’s killing.

The clarification helped quell immediate fears of a crisis in Malaysia-Iran relations at a time when Malaysia’s ruling Pakatan Harapan (PH) government has sought to adjust the country’s alignments in the Middle East and play a more prominent role there. But, more broadly, the ship seizure hype, along with other developments such as the killing of Soleimani, belies the bigger challenge for Malaysia of continuing to engage with Iran and being active in its Middle East diplomacy at a time when the region is undergoing heightened tensions.

As I have noted previously in these pages, Malaysia has long been a significant Muslim-majority country that has considered itself an active player when it comes to managing issues related to the Islamic world. As part of that, the country has maintained links to Iran over the years, which have come under scrutiny at various points, from illicit Iranian-linked activities conducted on Malaysian soil to the Southeast Asian state’s resistance to isolating Tehran at diplomatic fora (which has at times created differences with the United States).

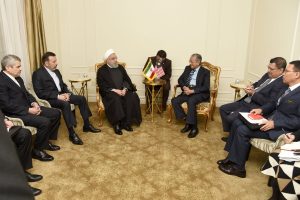

Malaysia’s ties with Iran have warmed under the PH government now led by Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad as the country seeks to elevate its role in the Muslim world as part of its broader foreign policy vision. Indeed, Mahathir has repeatedly spoken out against U.S. sanctions on Iran, and just met with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani during the recent Kuala Lumpur summit after a previous meeting last year in New York on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. This has continued despite the challenges Malaysia faces in warming to Iran, ranging from managing rivalries in the Middle East and ties with powers such as the United States abroad to dealing with other major priorities at home, some of which were at play in the recent summit.

This week, we saw another manifestation of this with a new round of hype regarding a ship seizure by Iran. On Monday, the website of IRIB state television quoted the Iranian Revolutionary Guards naval commander, Brigadier General Ali Ozmayi, as saying that Iran had seized a ship suspected of fuel smuggling and arrested “the ship’s 16 crew who are of Malaysian nationality,” prompting Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah to comment that Malaysia was seeking further clarification on the issue. On Thursday, Saifuddin clarified that, in fact, none of the 16 crew members on board the vessel seized were Malaysian, and nor was the vessel owned by Malaysia.

In the immediate sense, the clarification extinguished the latest round of speculation around the ship seizure that had persisted over the past week. Before Saifuddin’s comments, there had been fears that that Malaysia-Iran relations could be complicated and the PH government’s approach to the Middle East could once again be under scrutiny after the issues we saw at play during the Kuala Lumpur Summit.

But more broadly, it nonetheless obscures the bigger challenge for Malaysia, where the PH government is engaging Iran and promoting a more active role in the Muslim world at the very same time that we are seeing growing scrutiny on Tehran as well as continued turmoil in the wider Middle East. While this particular ship seizure may not have involved Malaysia, it is just the latest in a series of them that could still pull in the country in the future as it has other neighboring Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines. It also comes amid broader developments related to Iran over the past few months, from protests threatening the regime’s security to its continuing tit-for-tat with the United States, which shows few signs of ebbing anytime soon with the U.S. killing of Soleimani.

To be sure, Malaysia is accustomed to managing its ties with Iran and other Middle Eastern countries in the midst of broader pressures and challenges. And we have yet to see how events such as Soleimani’s killing will actually factor into broader regional dynamics in the Middle East and how they will affect or not affect the interests of extraregional states like Malaysia. Nonetheless, given where we are, the events of this past week should give us more reason to watch how Malaysia’s approach to Iran and the wider Middle East in its foreign policy continues to evolve amid the opportunities and challenges that it presents.