Late last month, the island of Chuuk — one of four main islands comprising the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) and also home to nearly half the country’s population — postponed a referendum vote on secession for the third time since 2015. Chuuk’s secession vote was supposed to have taken place this month, but the new vote is now scheduled for 2022. At least for the time being, Chuuk’s decision is a significant victory in the United States’ diplomatic, economic, and security competition with China in the Pacific Islands.

As part of Oceania, the Freely Associated States (FAS) — a group of sovereign nations including FSM, Marshall Islands, and Palau — are feeling the effects of growing Chinese pressure. The FAS maintain unique international agreements with the U.S., known as the Compacts of Free Association (COFAs), in which Washington provides yearly economic assistance and other benefits in exchange for exclusive military access to the FAS — an area of ocean roughly the size of the continental United States. Indeed, my RAND colleagues and I have described the region as “tantamount to a power projection superhighway running through the heart of the North Pacific into Asia, connecting U.S. military forces in Hawaii to those in the theater, particularly to forward-operating positions on the U.S. territory of Guam.” Thus, any disruption to the COFAs could greatly complicate the ability of additional American forces to access Asia in a wartime scenario.

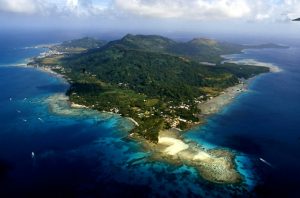

And this is precisely why Chuuk’s decision is so important for Washington. By forgoing the secession referendum once again, Chuuk will remain in the COFA, allowing the U.S. to retain exclusive military access to Chuuk. The island is contiguous to forward-deployed U.S. forces on Guam and boasts one of the largest and deepest lagoons in the Pacific. These natural features along with its strategic location made Chuuk lagoon an ideal base of operations during World War II for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Tokyo was able to project power from Chuuk against the U.S. military as it approached mainland Japan, forcing American troops to endure a very bloody and lengthy island-hopping campaign.

Beijing has almost certainly taken extensive notes of this military history. Chinese officials and researchers have variously discussed the need for Beijing to break out of not only the First Island Chain, but eventually the Second Island Chain as well, of which the FAS are apart, to enhance power projection in the open ocean and defend mainland China. Although media reporting on Chinese activities in Chuuk are sparse, the locals acknowledge that Beijing is attempting to play a larger role on the island. China, for example, recently pledged to build roads on the island, and it funded construction of the Chuuk government complex.

If the COFA no longer applies to Chuuk after a successful secession vote, then China would be able to interact with Chuuk bilaterally and on military issues. At present, the COFAs forbid the FAS from having military-to-military relations with any country other than the United States. A post-COFA paradigm would likely see China attempt to persuade the Chuukese leadership to sign decades-long land development leases. Beijing has already convinced another main island of FSM, Yap, to sign a 99-year land development lease encompassing a significant amount of land there (lengthy Chinese land leases are becoming a common trend globally — see Solomon Islands and Sri Lanka for example). However, Beijing is limited to commercial activities on Yap due to the COFA. It would have a freer hand in Chuuk if secession passes, and considering the island’s extraordinary military value, the stakes are clearly much higher.

Although Chuuk’s decision to postpone the vote is good news, Washington is certainly not out of the woods yet. The new vote scheduled for 2022, if it happens, is inconveniently timed to occur just before 2023 when the yearly funding component of the U.S.-FSM COFA is set to expire. It is unclear how Chuuk independence might impact this process, but secession certainly would be an unwelcome development.

From a broader perspective, FSM is the only FAS country that recognizes China over Taiwan. As a result, FSM already receives Belt and Road Initiative funding and Chinese President Xi Jinping has lavishly hosted FSM presidents, including the current one, David Panuelo, in Beijing. Fortunately, Washington has taken notice and responded in kind. In May, President Trump became the first president to meet with all FAS leaders at the White House, and in August, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo became the first sitting secretary to visit FSM. But more should be done.

Going forward, the U.S. and FSM should continue to prioritize frank, working-level discussions on issues of mutual concern in bilateral relations. This should include the long-term implications of China’s growing influence in Micronesia, and the potential consequences of Chinese military access to Chuuk if a secession vote were to pass in 2022 or beyond.