Recently, one story that attracted good deal of attention among South China Sea watchers is the allegations by the Beijing-based South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI) that an armada of Vietnamese fishing trawlers swarmed the waters off China’s Hainan Island. Based on given sets of data about ship flags and locations at certain time stamps, which were said to be collected from AIS (Automatic Identification System) signals, the SCSPI claimed that Vietnamese fishing vessels were doing illegal fishing — or even conducting close-in surveillance of the strategic Yulin Naval Base — in a big number.

The allegations were important, within the context of both scrutiny on the behavior of South China Sea claimants as well as the need for growing transparency in the maritime domain more generally. But a closer evaluation of those allegations and the evidence presented reveals more questions than answers.

The Allegations in Context

Before delving into some of the more specific issues, it is worth noting why the notion of a strategic encircling of China’s Hainan island by Vietnam in such a way would seem rather farfetched. Specifically, the allegation of these actions makes little sense for at least three reasons.

First, if there was indeed such a strategic swarming on the part of Vietnam directed at Hainan that would be of concern to China, it would seem that the Yulin Naval Base, which houses Chinese nuclear submarines, is thinly protected. That seems rather unlikely for those with knowledge of China’s military capabilities.

Second, Vietnamese fishermen would have to have been quite reckless to turn on their transponders while doing IUU fishing or conducting reconnaissance operations. Suffice it to say, this would be a deviation from the pattern we usually see in the South China Sea.

Third, if the vessels were there seeking fish, it would quite irrational as the area near the Chinese shore in question is well known as largely fished out. Chinese fishing flotillas, the world’s largest fleet, have reportedly had to venture afar to get catches. It is also highly doubtful that notoriously aggressive Chinese coast guard vessels were strangely benevolent enough to allow a big number of foreign fishing vessels to loiter so close to their strategic naval base for a significantly long time.

From a policy point of view, the last thing Vietnam desires is to create an excuse for the more powerful claimant to intrude into its waters. When asked, authoritative sources in Vietnam rebuffed the SCSPI claim outright. Vietnamese fishing vessels might be near Hainan Island, but they may just make normal passage or authorized port calls for replenishment. These activities are not unlawful under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

At the official level, Hanoi does not have a policy to encourage its fishermen to engage in IUU (illegal, unreported, and unregulated) fishing, or to conduct close-in intelligence gathering in the territorial seas of other countries. It is true that Vietnam has fishermen crews are trained as self-defense maritime militias. However, their status of maritime militia is only activated when needed and for defensive and search-and rescue missions only. The idea of using fishing vessels to track the Chinese submarines’ activities near Yulin base does not make any sense militarily.

The Data Discrepancy Issue

Having looked at the broader notion of what had been alleged to have occurred, we can now delve into some of the data provided by SCSPI. After some examination, it is clear that there are some questions regarding the reliability of the data.

Setting aside the legal question about the overlapping area beyond the Gulf of Tonkin and the rights of transit by the fishing vessels, my colleagues and I made a thorough examination into this body of data published on February 3, 2020 by the SCSPI (reportedly using the Vessel Finder or Ship Finder platform) about 34 allegedly Vietnamese-flag ships reportedly appearing in the vicinity of Hainan Island. We searched the database given Marine Traffic, a reliable commercial site for ship tracking, which provides animated replays of vessel movements going back over the last one year. The findings showed huge discrepancies between the two bodies of data provided by the SCSPI and Marine Traffic. Those discrepancies are listed below:

1) Six vessels in the SCSPI list have completely no records of these MMSI(s) in the Marine Traffic list, including VAN VINH (MSSI 574910016), TUNG LNOI B12 (MSSI 574090225), TRUNG LNOI (MMSI 574560735), 54 D 24 (MMSI 574565788), CAO TOM 08 (MSSI 574565157), BA THA LNOI (MSSI 574098036) (See Appendix 1).

2) 21 vessels in the SCSPI list have no records of activities or movements in Marine Traffic around the dates and times presented by the SCSPI. These include THUYEN 87 B5 (MMSI 574090872), LAI 39 (MMSI 574020046), SH (MMSI 574565090), SEN 66 (MMSI 574070012), PHUC B12 LNOI (MMSI 574098661), PH2 LUOI, or other names (MMSI 574000002), MRT 96 or other names (MMSI 574000096), MRT or other names (MMSI 574000088), LUOI NOI B40 (MMSI 574090354), LINH D17 (574094661), HANH 13 (MMSI 574562942), GION LNOI (MMSI 574098306), GIATHINH43 A9 (MMSI 57462675), GIA VY 84 B39 (MMSI 574094484), DUNG LUOI NOI B39 (MMSI 574480055), 90 PHUONG LCANG D34 (MMSI 574560504), 87 A17 (574000087), 6NO LUOI NOI (MMSI 574098234), 49 THANH LNOI B5 (MMSI 574098949), 3THAO 41 A37 (574098741), and 10 CHAU 85 D3 (574094985). However, there are still records of these vessels on other time stamps registered by Marine Traffic (See Appendix 1). It should be noted that both Marine Traffic and Vessel Finder used Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).

3) Four vessels, namely 98 LUOI NOI B 24 (MMSI 574560659), DUNGLUOI CAN N01B39 (MMSI 574020046), HUNG94899LU (MMSI 574070048), and 94MAI E21 LUOI CANG (MMSI 574020014), have records of activities on Marine Traffic around the dates given by SCSPI, but they were located at different places at different times by the Marine Traffic and SCSPI lists. The records from Marine Traffic showed these vessels all in the vicinity of Da Nang, not anywhere near Hainan. If both Marine Traffic and SCSPI provide accurate information, these vessels should have moved from one place to another within the time gap.

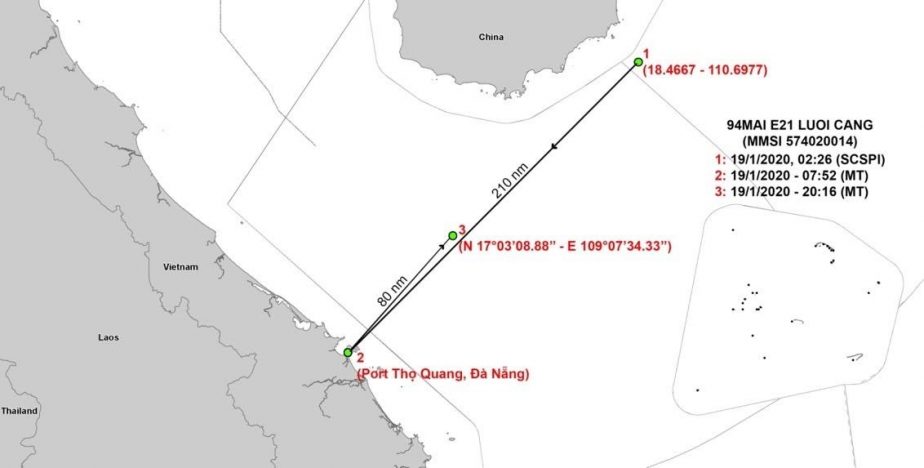

If so, one particular vessel shows a very abnormal movement. On January 19, 2020, vessel 94MAI E21 LUOI CANG (MMSI 574020014) traveled a distance of 377 kilometers (equivalent to 203 nautical miles) from a point off the east coast of Hainan (recorded by SCSPI) to the Tho Quang Wharf, Da Nang (recorded by Marine Traffic) within about 7 hours, and then left immediately to the area between Da Nang and Hainan. If this is the case, the speed of the boat would be about 30 miles per hour, which is impossible for a fishing vessel (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Distance Supposed to Have Been Traveled by Vessel 94MAI E21 LUOI CANG (Map by East Sea Institute)

4) Three vessels were recorded by Marine Traffic operating in the vicinity of Hainan Island on the dates and times given by the SCSPI. The vessel QUYEN 09 GIA A10 (MMSI 574000009) departed from Da Nang. However, it is not clear whether this vessel is doing IUU fishing or just exercising a normal transit through the area.

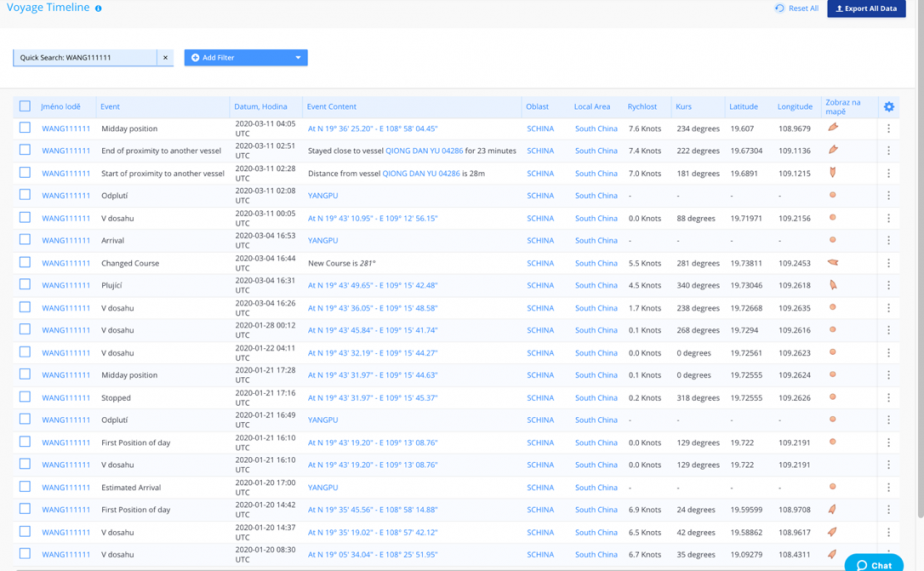

Two other vessels are quite interesting. Vessel WANG111111 (MMSI 574811111) and 11 336 (MMSI 574868866) did operate in the Hainan waters on January 20 and 21. Strangely, though having the Vietnamese MMSI number, these ships have never been visited any Vietnamese ports since March 25, 2019. Following their itineraries, these vessels have been recorded to visit Yang Pu, Hainan many times, which seems to be their home port. So, it is rather a strange fact if they are designated as Vietnamese trawlers. There would have been something wrong with their MMSI and AIS signals (See Figure 2), or suspected Chinese ships carrying Vietnamese-designation signals.

Figure 2: Voyage Timeline of WANG111111 on Marine Traffic (accessed March 11)

These discrepancies raise serious questions about the reliability of commercial AIS data in general and SCSPI records in particular. Though gaps could result from the difference between satellite and terrestrial AIS, it is quite skeptical that just a single one out of 34 SCSPI cases could be confirmed by Marine Traffic. Also, the cases of WANG1111 (MMSI 574811111), 11 336 (MMSI 574868866), and many other vessels having one MMSI number but carrying many names detected by Marine Traffic would be suspected AIS spoofing, which has been quite popular among the Chinese fishing world.

More generally, a real deficiency is that we are unable to check the dataset on other platforms such as China-based Ship Finder, or Vessel Finder, as these sites only offer 14-day or 30-day tracking history at the maximum. This should serve as a case in point for various platforms to share details with each other for the sake of comparison and verification.

Future Implications

While there are obviously issues with data that need to be addressed, this case does offer some implications for analysts and policymakers alike.

First, it is important to be cautious about any allegations that surface. For instance, with respect to this episode, despite some leading Chinese experts citing data surfacing from SCSPI, a more considered approach would be to ensure that any set of AIS data should first be carefully crosschecked against other sources to make sure that it is correct and accurate. Data can be fabricated, manipulated, and misinterpreted.

Second and more generally, it is worth recalling that positioning systems and the data they offer have their limitations. Positioning systems just provide the locations, trajectories, and courses of the vessels, saying nothing about the ships’ actual activities. From an international law perspective, fishing vessels enjoy rights to transits and authorized port visits for water supplies and replenishment.

Third, broader context matters. At the same time that the SCSPI allegations surfaced, they also came amid increasing concerns about China’s use of maritime militia to gain ground in the South China Sea. The Washington-based CSIS’ Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative (AMTI) revealed immense information about the incursions of Chinese fishermen into other countries’ exclusive economic zones and the presence of Chinese maritime militia around Thi Tu islet, which is under Philippine control. While there may be an effort to spotlight the activities of other claimants as well, the use of certain images, including one of a Vietnamese fishing vessel encountering a surfacing Chinese submarine taken by a Vietnamese fisherman in the northeast of the Paracels to illustrate the tracking of Chinese submarine near the Yulin base, can make these allegations look like deliberate misinformation.

Fourth, there are things actors can do to manage the situation, particularly for the sake of greater clarity and transparency on maritime claims and activities in the South China Sea. In this context, the hope is that irrespective of the validity of the concerns raised by the SCSPI, the debate that it stimulates should be viewed as a step forward in the right direction for the sake of greater transparency of maritime claims and activities in the South China Sea.

At least three things come to mind in this respect. First, claimants should clarify their maritime claims and the limits of their jurisdiction under UNCLOS for monitoring and lawful enforcement. Second, coastal countries should invest more in MDA/MSA capabilities to manage their marine assets, making sure that their activities comply with international law. Third, given the differences among different marine traffic data sets, a regional mechanism should be set up for countries to share and crosscheck information and data with regards to maritime activities to make sure that unlawful behaviors are detected and sanctioned.

Editor’s Note: After this piece was published, SCSPI responded to these and other questions in a posting on its website.

Dr. Do Thanh Hai is a senior fellow at the East Sea (South China Sea) Institute at the Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam. The author would like to express sincere thanks to the Institute’s staff for data collection and cross-check and many experts in the field for their critical comments. The views expressed in the article and all shortcomings are the author’s own.