We often misunderstand and underestimate the importance of foreign policy events for domestic politics. Americans tend to treat as a truism the idea that foreign policy makes little difference in elections, and that voters rarely pay attention to what happens outside the borders. In fact, though, we know that international events can often have deeply consequential and unpredictable effects on domestic politics. A new book by Seth Offenbach, The Conservative Movement and the Vietnam War: The Other Side of Vietnam, investigates how political conflict over the Vietnam War helped fuse the disparate elements on the American right into a cohesive movement that would put first Richard Nixon and then Ronald Reagan into the White House.

Several scholars of U.S. foreign policy and the history of American conservatism offer a detailed discussion of the book at H-Diplo. While anti-communism certainly characterized the Republican coalition in the 1950s, support for the Vietnam War on the part of U.S. conservatives was hardly a done deal in the early 1960s. Mark Hatfield, an anti-war Republican, delivered the keynote speech at the 1964 Republican Convention, at a time well before conservative movement had developed a coherent position on the war. Libertarians who supported Barry Goldwater often got cold feet about statist measures such as the draft, and even among fierce anti-communists there was dissent over whether Vietnam was the right war at the right time.

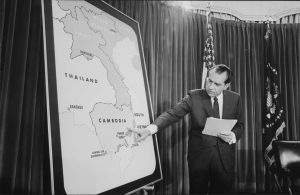

By the early 1970s, however, evangelical revulsion to the New Left came together with longstanding anti-communism to form a new template for a conservative candidate who could pull the factions together. Reaction to the perceived excesses of the New Left, which itself was deeply fragmented and really only unified on the question of opposition to the war, dovetailed with skepticism over Johnson’s management of the war and disapproval of his broader social program. While Nixon’s decision to wind down and end the war proved difficult for anti-communist conservatives to accept, eventually they developed a narrative in which the sins of the Johnson administration had scuttled the war effort abroad, while the treasonous nature of the New Left had undermined resolve at home. By 1980, if not earlier, Ronald Reagan could run on a platform of fierce opposition to communism abroad and fierce opposition to the ghost of the New Left at home; for his supporters, these became two sides of the same coin.

It is undoubtedly fascinating that conservative movement politics in the United States owe such a tremendous debt to the outcome of civil wars in East Asia. The McCarthy movement, which both mobilized the right and threatened to fracture it in the 1950s, emerged from a reaction to the Chinese Communist Party’s victory in the Chinese Civil War. The impact of the Vietnam War on the national psyche was much deeper, and its resonance has lasted even longer. Offenbach’s argument also has some personal resonance. Although not strongly religious, my own grandparents were committed Reagan Republicans who strongly opposed the Vietnam War, in no small part because one of their sons had been drafted and killed in 1967. The association of anti-communism with reaction to the New Left had, by 1980, smoothed over any concerns they had with Reagan’s muscular, confrontational approach to foreign policy. Vietnam was where Johnson had failed, and a conservative either would have done it differently or not done it at all. Although Ronald Reagan believed in the war and supported it wholeheartedly, he could frame himself as someone who could have stopped Vietnam from inflicting deep wounds on U.S. culture and society.