Nothing is more global than a pandemic. And there is no individual more quintessential to globalization than the migrant worker. Today, Singapore has 1.4 million foreigners working in-country, out of a total workforce of 3.7 million. Of these, 981,000 are low-wage migrant workers on temporary visas, many of whom remain in Singapore even though most work has ceased.

International commentators deem Singapore a success story in pandemic management, but the extent to which this success extends to migrant workers is doubtful. On April 6, in a widely-shared Facebook post, a prominent civil servant called migrant dormitories a viral “time bomb waiting to explode.” He was referring to the migrant workers quarantined in dormitories after authorities noticed COVID-19 transmission on the premises. By now, the government has fenced off four dormitories containing 50,000 workers, in effect protecting the surrounding local population while risking the health of the migrants.

This is not the first time that the Singapore government has treated migrant workers as a threat to be contained. In 2013, an Indian migrant worker was killed in a bus accident, reportedly causing 400 workers to react violently. The Singapore government immediately instituted a two-day alcohol ban in the vicinity. Today, alcohol sales are still restricted in the area, while recreational facilities in dormitories have been built to divert migrant workers from public spaces. COVID-19 has heightened similar anxieties over the need to restrict migrant workers to designated spaces.

But the pandemic has also exposed a longstanding callousness toward this population. A letter by the local NGO Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) pointed out the “undeniable” need for the government to announce plans to rehouse workers to “give reassurance to the resident and non-resident community.” The letter was prescient, appearing in the national newspaper a week before cases first appeared in migrant dormitories. The coronavirus has revived concerns for the health and safety of workers crammed onto the backs of open-deck lorries, yet these concerns have been voiced for at least 10 years.

Migrant dormitories have contributed 345 COVID-19 cases so far. On April 8, the Singapore government announced that all migrant workers staying in “non-quarantined” dormitories would “not be able to move out” for at least a month. Singaporeans, too, are now largely confined to their homes, but can access parks, supermarkets, and “essential services.”

Pandemics Exacerbate Precariousness

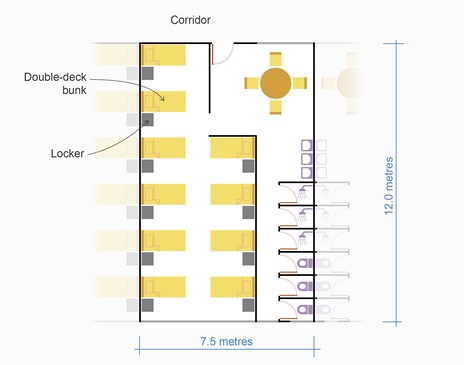

The primary risk that the pandemic poses to migrant workers is, of course, infection itself. Dormitories usually house male construction and shipyard workers from India and Bangladesh. Building codes indicate that workers in these facilities need only have 4.5 square meters of “living space,” including living quarters, dining, and toilet areas. In practice workers share showers and sleep on bunk beds, separated from each other by less than a meter. The WHO’s social distancing guidelines are near-impossible to achieve under these conditions. These living conditions affect approximately 200,000 workers in purpose-built dormitories and 100,000 in “temporary dormitories” converted from disused industrial sites.

Schematic sketch of a stereotypical dormitory room, based on Singapore’s building codes. (Source: Transient Workers Count Too)

Unlike hundreds of thousands of travelers who have flown home to wait out the pandemic, most of Singapore’s migrant workers remain there. One reason for this is the debt incurred by incoming migrants. Bangladeshi migrants to Singapore pay up to S$17,000 (US$12,000) for their first job in Singapore. This can take between one to two years to pay off, with 74 percent of Bangladeshi migrants earning less than S$25 a day. Another is migrant families’ reliance on remittances, with nearly half of Bangladeshi migrants providing for their families’ basic needs. Wages are hence of utmost importance to migrants and their families.

Singapore’s pandemic containment strategies may amplify pre-existing wage issues. The Ministry of Manpower has announced that “affected workers” will continue to be paid basic salaries in dormitories officially designated as quarantine sites. However, it is unclear whether salary deductions will be used to pay for catered food in these dormitories. This is concerning as employers are known to take unauthorized deductions, including for food and lodging, from workers’ wages. Existing research criticizes Singapore’s labor laws for condoning errant employer behavior, such as the manipulation of evidence for salary claims.

Debbie Fordyce of TWC2 is concerned that workers living outside of the quarantined dormitories are falling through the cracks. “The government says they will get food,” she says, “but this is on the assumption that employers are providing food.” Indeed on April 7, authorities announced that “employers should be able to continue to pay their salaries and provide accommodation and food,” urging employers to pass support measures onto workers. This statement shifts responsibility for the basic needs of migrant workers onto employers, without saying whether authorities will enforce their provision. Migrant workers who are recuperating from a workplace accident are in a particularly precarious position. As they cannot work, employers are disincentivized from providing them with food. “We know of many people like this who are not getting food,” Fordyce says. “We are overwhelmed with requests.”

The Mental Health Toll

Singapore’s migration regime ensures that migrant workers do not sink roots in the country. Work Permits, issued to workers earning less than S$2,200 a month, bar migrant workers from applying for permanent residency or citizenship, and must be renewed every two years. This deters migrant workers from forming permanent social bonds in Singapore.

The coronavirus affects migrant workers’ relationships with parents, children, and spouses in their home country. A migrant worker interviewed by TWC2 recounts how his mother calls several times a day, to ask if he is washing his hands and going out. Precarious wage situations also create significant emotional stressors: migrants are out of work, in crowded living conditions, and uncertain of how they can provide for families. Research shows that 62 percent of Indian and Bangladeshi migrant workers exhibit signs of significant psychological distress. Most in this group had unpaid debt or were off work due to a workplace injury. Current conditions reproduce these problems for an even larger proportion of migrant workers.

Phone calls are a lifeline for migrant workers in difficult times. To stay in touch with family, most migrant workers rely on WiFi where they can find it. This, too, is a livelihood strategy that allays the costs of debt-financed migration. However, workers in dormitories have little or no WiFi access, nor do they have the money to top up prepaid SIM cards. In response, TWC2 launched a SIM card campaign, aiming for S$20,000 in donations.

The response was astronomical: in five days, TWC2’s SIM card campaign raised S$127,000. More broadly, concerns that quarantined migrant dormitories would become “Diamond Princess all over again” – referencing the quarantined cruise ship in Japan that became a hotspot for infections — created a groundswell of sympathy for migrant workers. A spreadsheet collating cash and kind donation drives for migrant workers is circulating among Singaporeans. It attests to the range of initiatives seeking to alleviate migrant workers’ needs, ranging from masks and hand sanitizer to legal help and counselling.

However, organizers worry that a lack of transparency hampers relief efforts. Besides the four dormitories designated as quarantine sites, the government has not set clear guidelines for migrant dormitories, where individual dormitory operators decide what donations can be received. Organizers coordinating donations are constantly catching up with the dos and don’ts enforced on each site.

The migrant worker situation is symptomatic of Singapore’s model of economic growth. Migrant workers cannot buy SIM cards and worry constantly about remittances because they make barely enough to save. Densely packed dormitories result from an unflinching desire to keep wages low and profits high. Hence, the threat that large coronavirus clusters in migrant dormitories pose to the larger population directly relates to Singapore’s economic strategy too. Moreover, the current crisis exposes how the costs of this model are externalized into the public domain. “Now the costs are here, in terms of infection and costs to protect against infection,” Alex Au from TWC2 points out, “and they are public costs. This is the big picture.”

Live-in Domestic Workers Are Especially Vulnerable

Like migrants in the construction and shipyard sectors, migrant domestic workers face debt issues and maintain long-distance relationships with families back home. Singapore’s 256,000 domestic workers come predominantly from Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines. They live with their employers, and remain under this roof as social distancing measures tighten.

Domestic workers bear the brunt of housework in one-fifth of Singaporean households. This means that extra cleaning and sanitizing work is likely to fall onto their shoulders. Employers are understandably anxious about the pandemic, and hygienic homes benefit domestic workers too. However, domestic workers are unsure if they will be overworked and undercompensated. At present, Singapore does not have provisions for overtime work for domestic workers, but the law does stipulate that domestic workers be paid for work done on weekly rest days.

In March, the Ministry of Manpower advised that domestic workers remain in their employers’ homes on rest days. The Humanitarian Organization for Migrant Economics (HOME) has observed an increase in coronavirus-related calls to their helpline since. Domestic workers were unsure if they would be paid for working on rest days. Some felt compelled to work as they did not have their own room, and were under the constant scrutiny of employers, who were working from home themselves. A small number of domestic workers also reported salary issues and terminations as a result of the coronavirus. Employers have understandably been hit hard by the pandemic too. This is where government “advisories” are insufficient. Clear enforcement of rest days and wage protections for workers — and their employers — are critical to mitigating the impact of the pandemic on domestic workers.

The pandemic is particularly concerning for the minority of domestic workers subject to abuse. In the past, HOME’s shelter received domestic workers who had run away from these conditions and asked strangers to help them call HOME. Now safe distancing guidelines and “circuit-breaker” regulations make this impossible: domestic workers do not know where to run to, as few people are out on the street. Already, domestic abuse is on the rise in countries under lockdown. For domestic workers that are restricted from making phone calls, the pandemic poses the risk of abuse going unnoticed.

Domestic workers’ role in care work and housework is critical during these times. Yet whereas migrant dormitories draw public attention due to anxiety over rates of infection in crowded quarters, pandemic containment strategies shunt domestic workers into homes and out of sight. Without appropriate regulations that protect domestic workers’ wages and living conditions, tensions will rise in homes, hurting both employers and domestic workers in the process.

Migrant Workers Require a Redefinition of Vulnerable Groups

COVID-19 lays bare the relationships that sustain us. Around the world, people feverishly discuss trust in government, the place of family and friends amid crisis, and how Skype helps to weather the storm. Labor migration turns these issues on their head: the pandemic asks migrant workers to trust governments that are not their own, and to connect with family members at a distance, even when access to the internet is limited.

Right now, countries all over the world are turning inward, to protect the most vulnerable among them. Singapore too has sought to protect the elderly and the unemployed. But Singapore’s demography is unique: one in four members of its workforce are low-wage migrant workers, who are exceptionally vulnerable but not citizens. Moreover, vulnerability in coronavirus terms tends to be defined by age and immune systems. This obscures how the pandemic worsens migrant workers’ existing vulnerabilities to precarious work, mental health issues, and abuse. Indeed a limited, technical definition of health seems out-of-sync with everyday life itself. News outlets hurry to publish epidemiological models and pharmaceutical advances, as if these offer solace. Everyday life in isolation, sustained by being cared for and caring for others, says otherwise.

Societies should redefine pandemic management in wider terms. COVID-19 does not distinguish between migrant and citizen; hence migrant workers require the same access to safe distancing strategies as everyone else. However the coronavirus, and strategies to contain it, can have particularly adverse effects on this vulnerable group. For governments, this means tackling the pandemic in a way that addresses its toll on migrant workers’ livelihoods and wellbeing. Migrant workers must be assured that their wages are protected and that their basic needs for food and rest will be met. It is not enough to pass this task on to employers, who are also experiencing trying times. As Dr. Stephanie Chok points out, in Singapore the taxes that employers pay to hire migrant workers amount to more than S$2 billion per year. This money can sustain the welfare of migrant workers during this time.

Migrant workers expose the boundaries between the beneficiaries of Singapore’s coronavirus “success story,” and those who are systematically excluded from it. Sadly this is business as usual in a system that pursues growth at the expense of workers’ wellbeing.

Shona Loong is a DPhil candidate at the University of Oxford. She has published on migrant workers in Thailand and Singapore in peer-reviewed academic journals.