The Obama administration’s “Rebalance to Asia” and the Trump administration’s “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy” both included rhetorical commitments that the United States would do more in the Indo-Pacific region. Have words been matched by action?

Tom Donilon, President Barack Obama’s national security adviser, asserted that executing the rebalance to Asia “means devoting the time, effort and resources necessary.” The 2019 “Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy” stated that “President Donald J. Trump has made U.S. engagement in the Indo-Pacific region a top priority of his administration” and asserted that “under the Indo-Pacific strategy, the United States has increased its tempo and level of cooperation with allies and partners in the region.”

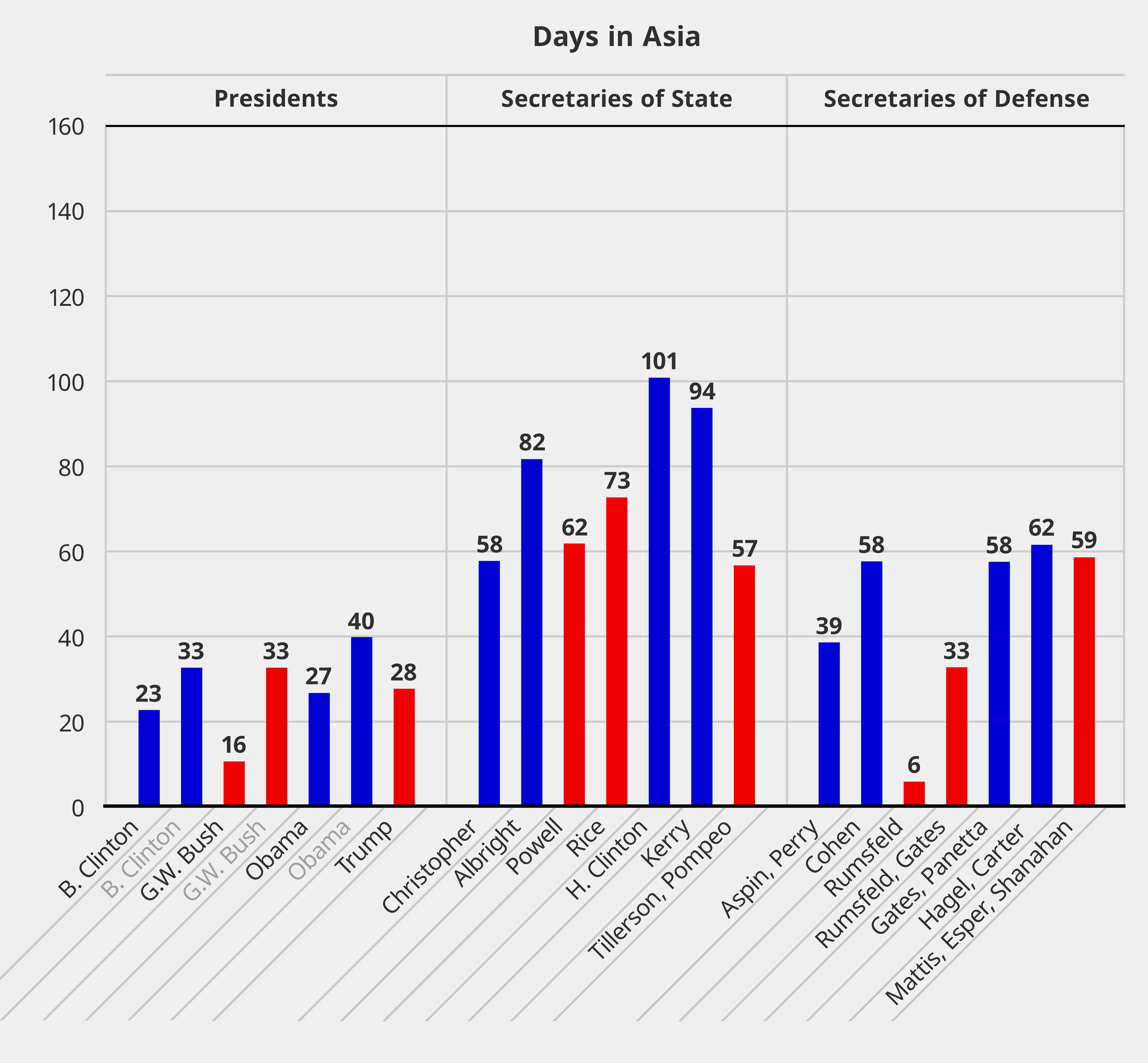

Given that the scarcest resource in government is high level attention, a critical metric of U.S. commitment is the amount of time spent in the Indo-Pacific region by senior administration officials. A previous study published in The Diplomat found that the time spent in Asia by the president and senior officials increased significantly from the first term of the George W. Bush administration to the second term, and increased further in the first term of the Obama administration.

This article compares the travel of the president, secretary of state, and secretary of defense from the Clinton administration through the Trump administration to see whether rhetorical commitment has been matched by resource commitments. If their claims are fulfilled, senior officials in the Obama and Trump administrations should spend more time in the Indo-Pacific than their Clinton administration counterparts (the baseline case) and Bush administration officials, who focused heavily on the Middle East in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks.

We count senior leader travel to Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, Central Asia, South Asia, and Oceania as Indo-Pacific travel; we exclude travel solely to Afghanistan and Pakistan, which is likely related to the war in Afghanistan. We focus on days in the region because the opportunity cost for overseas meetings is much higher than for Washington meetings, where no travel is required and other business can be conducted.

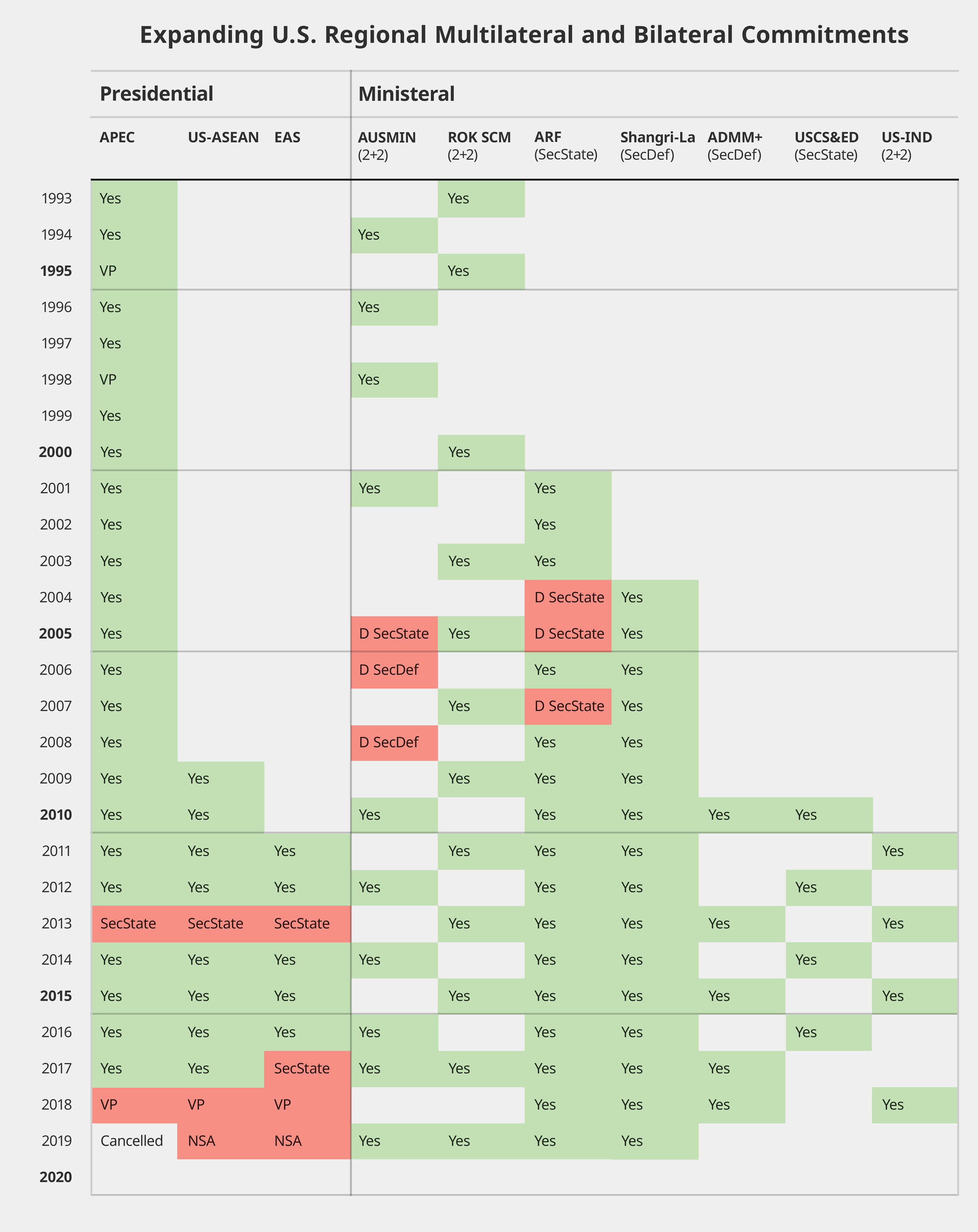

Attendance at regional meetings is an important symbol of the commitment the United States places on the Indo-Pacific region. However, such meetings have value beyond the specific agenda by providing a venue for U.S. regional messaging and policy initiatives, allowing senior U.S. officials to meet counterparts bilaterally on the margins of multilateral meetings, and providing opportunities to visit other countries as part of the trip. A major meeting requires the staff to prepare a variety of intelligence estimates, policy proposals, talking points, and speeches and forces the principal to spend considerable time focusing on regional issues. Multilateral meetings can also act as force multipliers, providing opportunities for senior leaders to engage multiple foreign counterparts without separate bilateral trips.

Time on Target

Both Obama and Trump have followed through on pledges to commit more time to the Indo-Pacific. Figure 1 shows that Obama spent more time in the region than his predecessors, and that Trump has spent more time in the Indo-Pacific in three years than Obama did in his first four. Although first term travel is the best comparison (presidents typically travel oversea more in the second term), Asian leaders will likely judge Trump against the 40 days that Obama spent in the region in his second term. Trump has currently spent 28 days in the Indo-Pacific and if travel continued at the same pace he would be projected to spend 36 days total during his first term. The coronavirus pandemic suggests he will fall well short of that projection.

Figure 1: Administration Travel to Asia. Note: All figures for the Trump administration are through three years, rather than a full four-year term.

Figure 1 shows that Obama and Trump administration senior official travel to the Indo-Pacific is only a little higher that the baseline set by the Clinton administration, although Obama administration Secretaries of State Clinton and Kerry traveled to the Indo-Pacific significantly more than their predecessors.

The Inescapable Pull of the Middle East

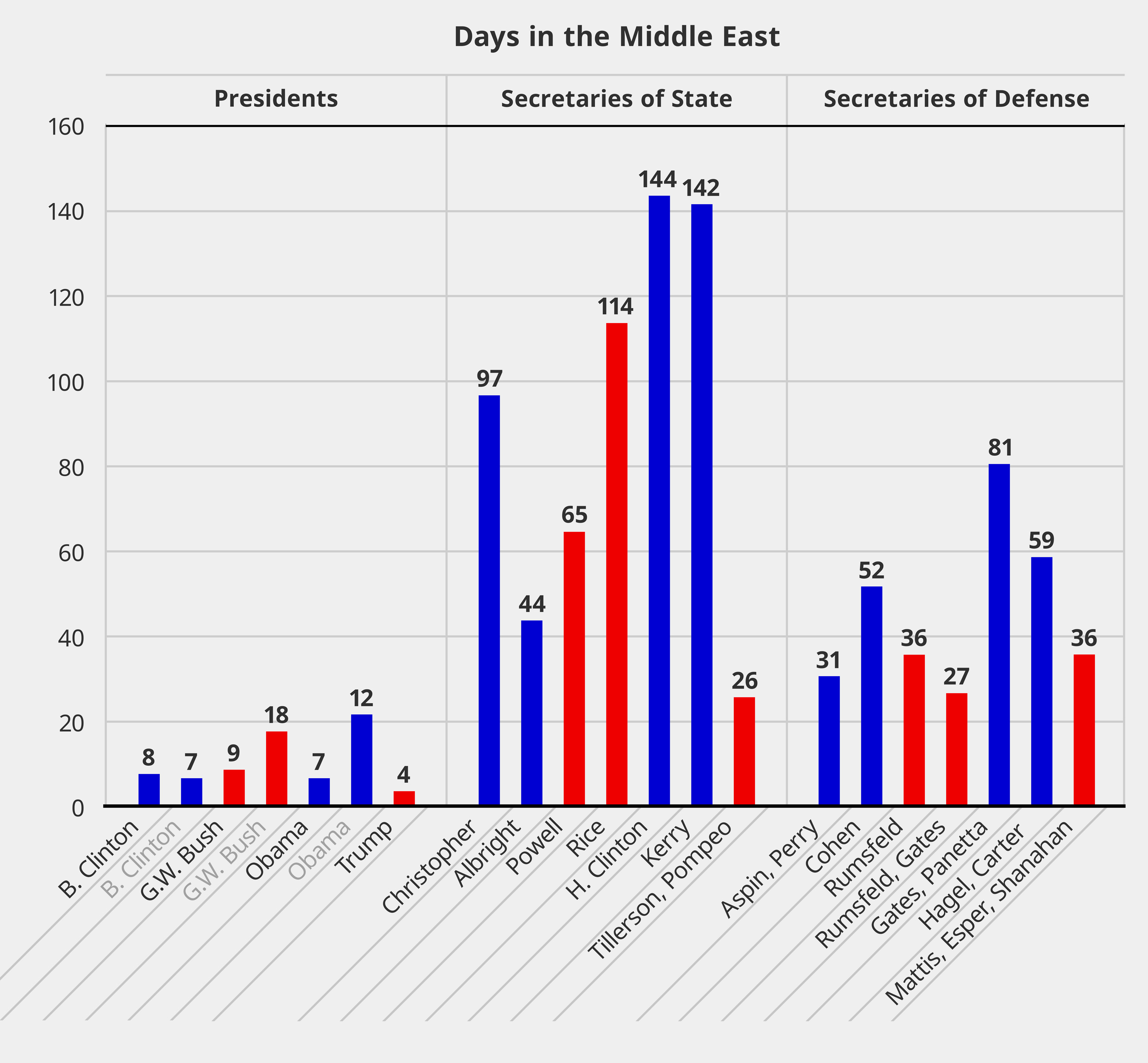

The Obama “rebalance” implied a shift of resources and attention from the Middle East to the Indo-Pacific, but Figure 2 shows how difficult this has been to achieve.

Figure 2: Administration Travel to the Middle East

The data show that Obama administration secretaries of state and secretaries of defense traveled significantly more to the Middle East that their Bush administration predecessors. From this perspective, the rebalance was less of a “pivot” away from the Middle East and more of an addition to an already busy travel schedule. Conversely, a decline in violence and a reduction of the U.S. troop presence in Iraq and Afghanistan has allowed Trump administration officials to reduce their time spent in the Middle East.

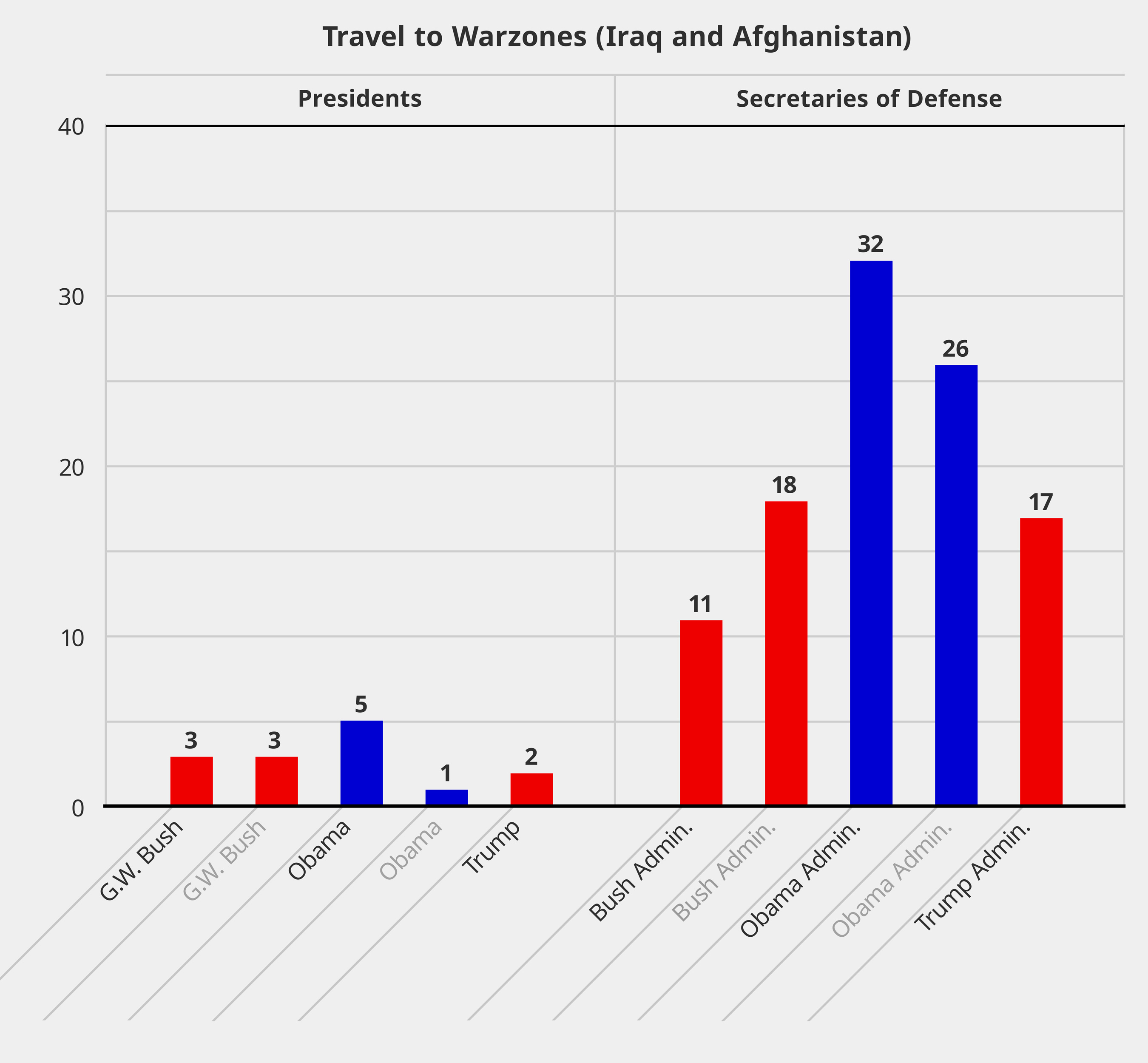

The methodology we employ assumes that senior official time spent in a region is a proxy for administration foreign policy priorities, but deployment of U.S. military forces in combat zones produces a political imperative for the president and secretary of defense to visit periodically to demonstrate their appreciation for the sacrifices the troops under their command are making. Table 1 shows that the need to visit war zones was a significant driver of presidential and secretary of defense travel to the Middle East.

Table 1: Presidential and Secretary of Defense Travel to Warzones (Iraq and Afghanistan)

Expanding U.S. Regional Commitments

Another means of demonstrating the priority the United States places on the Indo-Pacific is to join regional organizations that have annual meetings or to establish high-level political meetings to support U.S. alliances and partnerships. Regional multilateral meetings are typically hosted by member states on a rotating basis and specify the expected level of senior participation. Alliance/partnership meetings typically occur annually and alternate between hosting and visiting. The Obama administration believed that “more active U.S. participation in regional organizations was a necessary component of an effective Asia policy.”

Such meetings can be viewed as mechanisms for forcing senior administration officials to engage regularly with their regional counterparts and constitute a de facto floor for administration travel to the region. There is a significant reputational cost for breaking a regional commitment by being “absent without leave.” According to a senior Obama administration official, “Asian countries see such absences as confirmation that the United States does not give high priority to Asia.”

Figure 3 highlights a steady increase in U.S. multilateral and bilateral commitments to attend annual meetings in the region. The data show that these commitments have mostly been fulfilled, especially in the Obama and Trump administrations. Obama attended 18 of the 21 overseas regional summits scheduled during his time in office, and his secretaries of state and defense did not miss a meeting. Trump has only attended two of the eight regional summits scheduled during his term in office, but his secretaries of state and defense have fulfilled all their regional commitments. The Trump administration has also taken a page from the Obama playbook by establishing a new Quad (United States, Japan, Australia, and India) foreign ministerial meeting in 2019 that will meet annually.

Figure 3: Expanding U.S. Regional Multilateral and Bilateral Commitments. Note: The U.S.-Japan SCC (2+2) meeting is not shown, because all but two of the meetings have occurred in the United States (the U.S.-India 2+2 meetings for 2012, 2014, and 2016 are not counted for the same reason). The first Quad summit at the ministerial level occurred in 2019 in the United States and is therefore not shown.

The data reflect notable differences between the Trump and Obama administration approaches to the Indo-Pacific. Trump has spent more time in the region in his first three years than Obama did in his first four. However his travel has focused primarily on high-profile official visits to China, Japan, and India and bilateral nuclear diplomacy with Kim Jong Un. The Obama administration placed a higher priority on multilateral diplomacy, with Obama attending almost all of the APEC, U.S.-ASEAN, and EAS summits, while Trump has missed six of the eight multilateral meetings in the region.

What happens if the president or his senior officials don’t travel to the Indo-Pacific or skip key regional meetings and dialogues?

The November 2019 East Asian Summit (EAS) and U.S.-ASEAN summit illustrate the negative impact of being “absent without leave.” Regional media interpreted Trump’s decision to send National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien in his stead as a reduction in U.S. commitment. ASEAN decided to downgrade its representation at the U.S.-ASEAN summit, with seven of the 10 ASEAN countries sending foreign ministers instead of heads of state to meet with O’Brien. Instead of signaling increasing U.S. commitment, the summit meetings wound up supporting a contrary narrative of U.S. disengagement from the region.

Conclusion

Senior leadership travel demonstrates the willingness of presidents and their senior cabinet officials to engage regularly with their Indo-Pacific counterparts. This is not a perfect proxy for U.S. foreign policy commitment to the region, but it is an important “costly signal” given that the president and senior cabinet officials have many competing demands on their time and that the time and opportunity costs of attending bilateral and multilateral meetings in Asia are high.

Our methodology measures inputs (time senior officials spend in the region and whether they fulfill existing U.S. regional commitments) rather than outputs (a heightened sense of U.S. commitment to the Indo-Pacific among regional leaders, elites, and publics). The critical question is the extent to which costly inputs (senior leadership time) translate into the desired outputs (regional sense of U.S. commitment). The effectiveness of this translation depends partly on the content of the messages U.S. officials deliver in the region and whether these assurances are backed by appropriate U.S. policies and resource commitments.

A full assessment of effectiveness would require a comprehensive examination of regional perceptions of the reliability and depth of U.S. commitment to the region. Several authors have conducted such studies, most of which suggest that the Trump administration’s “America First” rhetoric and decisions to walk away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, renegotiate bilateral trade agreements, and insist that U.S. allies must pay more to support U.S. troops based in their territory have heightened regional concerns about U.S. commitment. To their credit, Trump administration secretaries of state and defense have fulfilled all their regional bilateral and multilateral commitments. However, it remains to be seen whether consistent U.S. attendance at ministerial level meetings can fully compensate for lower-level U.S. representation at regional summits.

Jonah Langan-Marmur is a Research Intern at the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs at the National Defense University, and a graduate student in Strategic Studies at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies.

Dr. Phillip C. Saunders is Director of the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs at the National Defense University.

The views expressed are their own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Defense University, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.