Pakistan civil rights group Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) lost another key leader and activist in an attack perpetrated by unidentified armed men on May 1 in the country’s South Waziristan tribal district bordering Afghanistan.

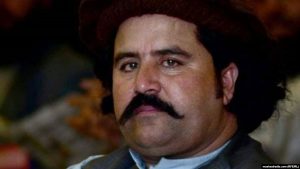

Sardar Arif Wazir, a cousin of Pakistani parliamentarian Ali Wazir, was targeted four days after his release from a Pakistani prison. He was arrested on April 17 on charges of delivering an “anti-Pakistan speech” during his visit to Afghanistan.

The 35-year-old has become 18th member of his immediate and extended family targeted since the launch of Pakistan’s anti-Taliban military operations in the tribal region in 2003.

Pakistani officials have been silent about the possible motive of the murder and the perpetrators. There has been no claim of responsibility from any armed group operating in the region.

PTM central leader and member of Pakistan national assembly from North Waziristan Mohsin Dawar, however, said in a tweet that “Arif Wazir was murdered by “good terrorists.” Our struggle against their masters will continue.”

The PTM and the “Peace Committee”

The term “good terrorists” refers to the pro-government armed groups that locals sarcastically call the “good Taliban.” The Pakistani government and military style the groups as a “peace committee.” The so-called peace committee members bear arms without being questioned by the security agencies. They support the military presence in Waziristan and fight against those Taliban who target the Pakistani security forces.

For years, leaders of the PTM, among other demands, have asked for the disbanding of the “peace committee” and across-the-board action against all armed groups, whom PTM leaders believe are posing a threat to the security of the common people.

Relations between the PTM and the Pakistani authorities remained tense over tricky issues such as the presence of armed groups and alleged human rights violations. And the latest killing has further antagonized the already tense environment.

Since its emergence in January 2018 as a nonviolent group campaigning for civil rights, PTM has openly criticized Pakistan military and its intelligence agencies, accusing them of human rights violations in the tribal region. The Pakistani authorities, on the other hand, accuse the PTM leadership of getting funds from Indian and Afghan intelligence agencies.

While the majority of Pakistani politicians, journalists, and rights activists bite their tongues and use various metaphors when it comes to the military and its intelligence agencies, the PTM leadership is willing to name names in its allegations of human rights violations in the name of anti-Taliban military operations.

The group’s initial demands included the clearance of unexploded landmines in the tribal areas, removal of unnecessary military checkpoints in the region, compensation for houses and businesses destroyed and damaged during the anti-Taliban military operations, release of the people picked up by intelligence agencies in the name of investigations and marked as “missing persons,” and impartial investigations into extrajudicial killings in the region.

Thousands from the tribal region immediately rallied to the PTM call. The presence of the military and various armed groups there have curbed freedoms, including the freedoms of movement, assembly, and affiliation, of the region’s fiercely independent people — besides damaging their properties, businesses, farming, and their social life.

In some estimates, the various armed groups that came to settle in the tribal region following the overthrow of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan in late 2001 had targeted and slaughtered nearly 2,000 well-known tribal elders or their family members. They were murdered for their opposition or noncompliance.

Since 2003, Pakistani security forces have conducted multiple large- and small-scale anti-Taliban operations in Waziristan. However, the tribal people expressed their reservations about those operations, mainly because they always resulted in civilian displacement and lost lives and property while the Taliban continued to hold ground and gain strength.

For more than a decade, the rest of Pakistan and the world was led to believe that it is the tribal people who support the Taliban and their Sharia system, supposedly because this is in accordance with tribal customs and traditions. However, the PTM leadership, the majority of whom are young men who grew up under the shadow of Taliban guns, dispelled that widely-spread perception by demanding peace and an end to all kinds of armed groups – whether “good” or “bad” Taliban – on their land.

The recent dispute that took the life of PTM leader Arif Wazir apparently stems from the presence of the same pro-government armed groups. According to some reports and accounts from locals, the so-called peace committee members regulate public life, collect taxes, punish alleged offenders, and silence government critics.

In June 2018, two PTM activists were injured in a clash with the “peace committee” members in Wana, the center of South Waziristan. Addressing a news conference in Islamabad soon after the incident, then-spokesperson for Pakistan Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR), the military’s media wing, Major-General Asif Ghafoor had said that “peace committee” members were infuriated by the PTM’s anti-military and anti-state slogans, which led to the clash.

The PTM is not the first to raise objections to the policy of distinguishing between “good” and “bad” in Pakistan’s approach to curbing militancy and its role in the anti-terror war. The United States, Pakistan’s anti-terrorism ally, has also been raising objections to the country’s role in fighting the Taliban.

Former U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, during her October 2011 visit to Pakistan, famously warned Islamabad that “you can’t keep snakes in your backyard and expect them only to bite your neighbors.” A month before that, in September 2011, another top U.S. official, then-chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen, called the Haqqani Network of the Taliban “a veritable arm of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency.” More recently, U.S President Donald Trump, in a January 1, 2018 tweet, accused Pakistan of “lies and deceit” in its fight against the terrorists that the United States is hunting in Afghanistan.

But Pakistani authorities strenuously disagreed. Pakistan says it rendered greater sacrifices than any other country in the anti-terror war. Prime Minister Imran Khan, in a tweet on November 19, 2018, said that “no Pakistani was involved in 9/11 [terrorist attacks] but Pakistan decided to participate in the U.S. war on terror.” Khan further added that his country suffered 75,000 casualties and over $123 billion in losses to its economy.

What Next?

Whatever his political views and his standing vis-à-vis the government, Arif Wazir was a Pakistani citizen and leader of a popular group, not to mention the cousin of a sitting MP. His tragic death was caused by unidentified attackers who also target the Pakistani security forces and civilians.

However, very few Pakistani television channels and newspapers reported on Arif Wazir’s murder. Besides, there was no condemnation of the attack by any top government official. Instead, a malicious campaign was launched on twitter against the Wazir family.

This will further alienate the youth and the people of Waziristan, who strongly believe that they are being oppressed both by militant groups and the state security agencies. This perception is rooted in years of frustration with successive governments that failed to bring a positive change in terms of infrastructure development, education, civic facilities, and legal and constitutional status. For decades, the tribal people used to be considered as second-class Pakistanis mainly because their areas were regulated under the colonial-era Frontier Crimes Regulation (FCR).

Although the tribal districts were merged into the adjacent Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2018 and the FCR law was repealed and replaced with the full sphere of the constitution of Pakistan, some parts of the tribal region remain information black holes. The information vacuum is keeping incidents of human rights violations from being reported in the media. One recent example is several protests by the locals, youth in particular, demanding the extension of mobile phone 3G/4G internet service in the region.

The government may not be happy with some of the PTM statements or their demands, but there is no denying the fact that the group’s activists always remained peaceful during their sit-in protests over the past two years.

It is high time for the Pakistani authorities to open a meaningful channel of communication and dialogue with the PTM leadership. Cornering them by gagging their voice in the media will lead to further alienation that may create serious problems in the future.