The tragedy was all too familiar in Myanmar’s infamous northern jade mining town of Hpakant: In the early hours of the morning, hundreds of jade pickers teetered on the edge of unstable mountains to scavenge the loose debris dumped by trucks. They are convinced finding a valuable stone will forever change their lives. When the mountain collapses miners are instantly enveloped by a wall of mud when a heavy landslide hits the bottom. Dozens instantly disappear and families are left without answers.

This year’s landslide was deadliest on record. The July 2 collapse at the Wai Khar mine left at least 175 dead, mostly men in their 20s, reportedly from as far away as war-ravaged Rakhine state. Last year, at least 50 people died, buried alive by the mountain, and in 2015, 113 died. Each disaster sparked calls for reform of the jade mining sector.

Thousands of young men from all over the country come to the mines in Hpakant to search for jade. The vast majority of them are considered “unauthorized jade pickers.” Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

“The tragedy at the Hpakant mines is not due to a natural disaster but is a human-made disaster. The core reason for these deaths is the central government’s poor governance of natural resources and environmental mismanagement and flaws in the extreme centralized quasi-civilian 2008 constitution,” said the Kachin Development Networking Group.

Kachin state’s Hpakant is the epicenter of jade mining and holds 14,000 hectares of the richest deposits in the country. The mine had officially closed down on June 30, but that didn’t prevent unauthorized jade pickers from working the area. Most days, such workers will go home empty handed, or make a few dollars on small stones. If they find big pieces, the company or boss they work for will take the stone and accompanying profits. With little transparency as to how these companies operate, it is close to impossible for victims’ families to receive any form of compensation from the government, or from the company their loved ones “worked” for.

Jade mines cover 14,000 hectares around Hpakant and have been excavated for decades leaving the environment barren and dusty. The pits at the bottom are full of water used by mining companies to do commercial mining. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

Broken Promises and Scant Oversight

Civil society groups monitoring northern Myanmar have characterized the governing National League for Democracy’s policy response to calls to reform the sector after recurring landslides as worse than under the military junta. After coming to power five years ago, State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi’s NLD government promised to undertake real reforms, but weak legal frameworks remain and little progress has been made. Suu Kyi instead noted that miners there disregarded that the mine was already closed and said, “most of these victims are illegal miners.” She went on to say that “it is difficult for the country’s citizens to get legal jobs, and that generating jobs should be a priority.”

A closer view of jade pickers on the side of the mountain searching for stones after mining trucks have dumped their debris. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

Myanmar watchers are skeptical that the “investigative body” announced by the government will yield any real results, or that there will be any strengthening of new regulatory measures. Critics fault repeated landslides with significant death tolls as the government’s unwillingness to enforce safety standards and on the mining companies which are allowed to operate in Hpakant.

“Five years after taking office and pledging to reform the corrupt sector, the National League for Democracy has yet to implement desperately needed reforms, allowing deadly mining practices to continue and gambling the lives of vulnerable workers in the country’s jade mines,” London-based environmental watchdog Global Witness said in a statement after the most recent tragedy. “The longer the government waits to introduce rigorous reforms of the jade sector, the more lives will be lost. This was an entirely preventable tragedy that should serve as an urgent wake-up call for the government.”

Miners sit on the edge of the mountain after searching for hours. The work is grueling and often, many leave with nothing. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

In 2014, the government of Myanmar joined the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) to increase transparency and accountability in how the country manages its natural resources. This was intended to make a publicly available list of active oil, gas, gemstone and mineral licenses, but much of the data is still incomplete. That same year, it temporarily stopped granting new licenses for a period of two years. Critics say that the Gemstone law, passed in 2019, does not go far enough in restraining the illegal mining business. A separate gemstone policy has yet to be implemented, which has blocked a more viable and long-term approach to mining jade.

Freed from Sanctions, Jade Business Thrives

After almost 20 years of American sanctions on the military junta in power for half a century, the Obama administration decided to change course based on its perception that real political reform was happening in the country. After restoring civilian rule through democratic elections, then-President Obama met with Suu Kyi in September 2016 and announced that all economic sanctions would be lifted.

A month later, after consultation with Suu Kyi, Obama revoked several executive orders related to Myanmar sanctions in December, he ended more restrictions on U.S. aid to the country. Heavily criticized by transparency watchdogs, Obama said in 2016, “It is the right thing to do in order to ensure that the people of Burma [Myanmar] see rewards from a new way of doing business and a new government.”

A view inside the mountain, where in the dry season, hundreds of trucks dig out jade. The scale is immense. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

The lifting of economic sanctions meant that a longstanding prohibition on Myanmar jade imports and companies associated with its operations inside the country would be removed from the U.S. Treasury’s blacklist. Juman Kubba of Global Witness said at the time, “The U.S. government is dropping one of the best sources of leverage over the former generals, drug lords and military companies who still secretly control critical industries like jade.”

Four years later, many are disappointed with the lack of progress made by the NLD and argue that the lifting of sanctions let the military off the hook in terms of accountability.

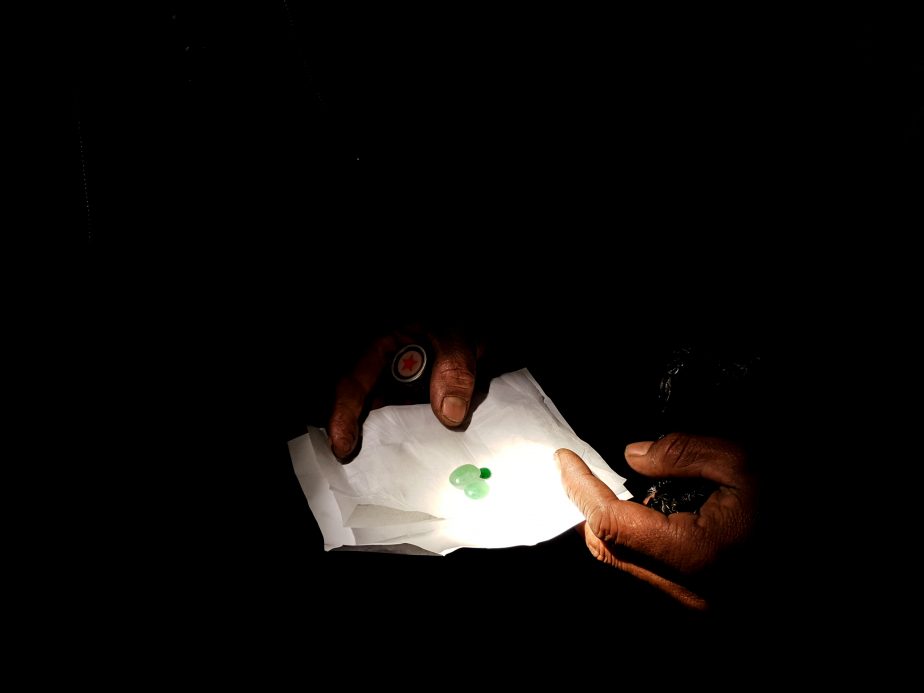

A miner examines the quality of the stone he has found by shining his light through it. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

The Journey from Mine to Market to China

The Hpakant mines are only 100 kilometers from Myitkyina, Kachin state’s main city, but it takes 6-10 hours via extremely rough, unpaved road to get there. Several checkpoints are set up along the way and foreigners are forbidden from entering anywhere close to the mining areas. Although illegal, Chinese buyers have increasingly made their way to the mines to cut out the middlemen. Bribes or “royalties” are paid to military commanders so smugglers are not stopped at checkpoints along the smuggling trail from Hpakant to Myitkyina to Mandalay.

For middleman Shima Verma, from Rakhine state, he and his family have been in the lucrative jade business for years. He says he makes dozens of trips between Hpakant and Mandalay per year and works with Chinese sellers at the market to facilitate deals. For the rocks he sells on average, he explains that the miner gets $60, he will get $150, and the Chinese seller will earn $500. He says he earns $2,000-$3,000 per month, ten times the average wage in Myanmar.

A man from Rakhine state shows the rock he is trying to sell at the Mandalay jade market. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

A share also goes to the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), to middlemen, and local bosses, leaving jade pickers 10-20 percent. The lion’s share of the industry, however, is controlled by the former military junta in the country. Although foreign ownership in Myanmar is illegal, the biggest producers are Chinese-owned shell companies from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. It is estimated that only 10-15 owners own about 100 large mining companies in the country. The Wai Khar mine is allegedly owned by five different companies. As is often the case, these companies are untraceable and there is little to hold them accountable when an accident happens. Around the whole mining area, these companies are often difficult to identify, are government shell companies with fraudulent licenses, or are financed by Chinese businessmen, sometimes dual nationals. Global Witness said it could be “the biggest natural resource heist in modern history.”

Jade pickers come from all over the country sell to work in the jade mines of Hpakant and then sell their stones at the Mandalay jade market, the largest in the world. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

A 2015 report by Global Witness, Jade: Myanmar’s Big State Secret, revealed the inner workings of the multi-billion dollar jade sector valued at $31 Billion. The report revealed an extensive network of untransparent companies tied to the Myanmar military, ethnic rebel groups operating in the area, the drug and arms trade, and Chinese businesses.

A young Chinese buyer measures the jade over a livestream for Chinese buyers. Even small pieces like these can be sold for thousands of dollars. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

According to sellers in Mandalay, thousands come to do business everyday in the largest jade market in the world. In the Mandalay market, sellers connect with Chinese buyers, many from the closest border town of Ruili in Yunnan, China. During the financial crisis, the jade trade slowed down, but by 2011, the thriving Ruili jade industry attracted scores of young people from all over Yunnan to work in the border town, refining stones to be sent to clients all over China. Chinese buyers sit and examine rocks of all sizes from Burmese sellers who are jade pickers themselves, middlemen, or Sino-Burmese businessmen. Some of the jade goes through official channels to Naypyidaw at gem emporiums, but most is smuggled through the black market into China through the nearest border. Only a small fraction of these revenues can be traced and end up being taxed.

Many Chinese buyers of jade come from the border town of Ruili. Three young women sell multiple jade items to clients over livestream e-ecommerce platform Taobao. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Before the pandemic, on the flight back to Mandalay from Myitkyina, I sat next to a Chinese jade trader from Guangzhou who said he had been in Hpakant several times in the last three years. There are direct flights from his city to Mandalay. He said he makes $4,000-$6,000 a month. The Chinese economy amid the coronavirus pandemic has experienced its worst economic slowdown since the 1970s, shrinking almost 7 percent. But the slowdown had already begun before the pandemic. “The economy is getting worse in China,” the man told me. “With the money I make from jade, I can easily buy a house and make a good life for my family. It would take me years to do that in an ordinary job in China.”

Fewer and fewer transactions are done in cash, but now with the prevalence of smartphones and high speed internet in Myanmar, most Chinese sellers hold livestream auctions for buyers online and sell the jade instantly, receiving money by Chinese apps such as WeChat or Taobao. These cashless transactions also mean revenues are harder to trace, with an estimated 80 percent of purchases tax-free. On the Chinese side, Ruili is explicitly referred to in the jade business as the Taobao Jade Market, set up jointly by the Chinese government and e-commerce giant Taobao.

A chinese seller at the Mandalay jade market holds a live auction over e-commerce platform Taobao to customers in China. Once the jade is brought into China, the jade is shipped directly to the client. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“Gold is valuable, but jade is priceless”

From the Chinese perspective, the symbolism of jade runs millennia deep, traced back to the Neolithic period as a symbol of prosperity among the elite. The jade obsession is almost exclusively Chinese and the demand for the stone is driven almost entirely by the dometic Chinese market. At the top end, the Chinese view the worth of jade more than gold.

A man examines refined jade rings from a Burmese seller. If the jade is in this form, they do not need to be smuggled but can be simply worn over the border to be sold in China. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Other jadeite deposits exist elsewhere in the world: Guatemala, Japan, Russia, and in the United States’ California, but it is most accessible on China’s doorstep through Yunnan, and Myanmar has the top quality jadeite. A “jade road” between the two countries existed since the end of the 18th century until World War II. Much of the trade thereafter shifted to Hong Kong, where dealers went directly to sell their stones, or through merchants from Yunnan.

Outside of the market, more unregulated jade transactions take place. It is difficult and expensive to get a place inside the market and lesser quality jade is traded outside the gates. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Three decades later in the 1980s, with free market reforms under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, jade demand skyrocketed again, shifting the craftsmanship and sales back to China. Emerging economic prosperity and increased demand for luxury products in China since the 1990s has augmented the Chinese rush for Burmese jadeite. As the sole driver of the price of “imperial jade” globally, and almost only of value in the Chinese market, it eclipses per-carat that of diamonds, rubies, and sapphires, which are popular in other parts of the world.

In the 1990s, the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), one of several ethnic armed groups which had been fighting the military regime for autonomy since 1961 along the countries’ frontiers, finally lost control of the valuable mines around Hpakant. From the Myanmar government’s perspective, the logic has been, the more jade reserves are depleted, the weaker the KIA will be. When jade mining began to boom in the 1990s, the town of Hpakant turned into a cesspool of crime, replete with drugs, prostitution, and arms trading.

A group of miners sit together examining their finds. People come from all over the country to try their luck in Hpakant. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

Now firmly in control, the military junta or Tatmadaw, continues to handsomely profit from China’s renewed demand in jadeite, allotting the most lucrative areas of the mines to themselves, and in opaque collaboration with Chinese companies. Consequently, this has diminished the profits of the KIA and fighting continued until 1994 when a ceasefire was signed. When that happened, thousands from across Myanmar flocked to the Hpakant area to look for jade.

Mining and selling starts in Hpakant in the early hours of the morning by thousands of migrants from all over the country. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

Under the 2008 constitutional framework, the military maintains wide-ranging autonomy and authority in many facets of operations in the country. Among the most prominent are its ownership of two large conglomerates owning a large number of businesses, including in the jade mining sector.

“The biggest problem is that the people have no ownership rights. A mutual sharing agreement that benefits the people there is very important for a jade mining area. The gains are only for the cronies and the people involved in the central government,” Tsa Ji, of the Kachin Development Networking Group, an association of Kachin civil society groups told Al Jazeera in 2015.

From 1994 until 2011, for nearly 17 years, the ceasefire between the Tatmadaw and the KIA held until fighting broke out again. Over the last decade, more than 100,000 Kachin and neighboring Shan state residents have been displaced by the conflict. Although diminished, the KIA still reportedly has its ways to extract its own revenues from local mining operations. Little to no revenue reaches the local Kachin population. Swedwatch said that, “the control over revenues from Kachin’s jade mines is a strategic priority for both sides in the ongoing armed conflict that has marred Kachin for six decades.”

According to The Irrawaddy, in mid June, the “(KIA) warned civilians in northern Shan State’s Kutkai this week that clashes could erupt anytime in the area between the ethnic armed group and the Myanmar military, or Tatmadaw.” The area is two hours from the Muse-Ruili border.

An older jade miner examines a rock he has uncovered. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

Coronavirus Changes

Although the country has so far been largely spared by the novel coronavirus, with just over 300 cases, it has shut down most of the corridors used to trade and smuggle jade, namely, across the Chinese border. This has already had major economic implications for those in the jade trade who cannot survive without buyers. Out of economic desperation caused by the pandemic, even more people have turned to working in the black market for local jade bosses.

The Mandalay jade market was closed in March after the government banned people from gathering in large numbers. It remains closed but the buying and selling of jade goes on in secret. There are internal travel restrictions and quarantine measures in place inside the country which limit the movement of people. Flights have stopped and Chinese business has significantly slowed, but the border is still open and some people have gone back and forth.

A jade picker uncovers a large stone from the side of the mountain. When jade miners uncover large stones, they are often taken by local bosses controlling the workers. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

The entire future of the industry is highly uncertain these days, at least until the rainy season ends. The shutting down of border crossings and trade has cost Myanmar millions per day since January, putting many out of work without any source of income to draw from in Kachin. It is unclear how much cross border activity is currently permitted.

As long as there is jade left in Hpakant, demands from human rights and civil society groups are likely to be left unheard. Accidents will continue to happen, and drugs will continue to flow in this multi-billion dollar shadow industry. Myanmar has set its next general election for November 8.

75-80 percent of jade miners are estimated to be addicted to heroin or meth in the mines. The easy accessibility quite often offered to them by local bosses or other miners. HIV rates are also disproportionately higher here than in other parts of the country. Photo by Hkaw Myaw.

“The longer the government waits to introduce rigorous reforms of the jade sector, the more lives will be lost. This was an entirely preventable tragedy that should serve as an urgent wake-up call for the government,” Donowitz added.

“The government should immediately suspend large-scale, illegal and dangerous mining in Hpakant and ensure companies that engage in these practices are no longer able to operate.”