Amid COVID-19 restrictions, campaigning activities are limited to the bare minimum for Singapore’s 2020 general election, set for July 10. There will be no physical rallies; instead, political parties are relying on livestream gatherings and social media communication to reach out to their constituents.

In a country with harsh restrictions on freedom of expression and assembly, a de facto limitation of campaigning to social media could be an opportunity to observe a fairer election process. The asymmetry of resources needed for physical campaigning and to mobilize crowds would be cushioned by the equalization effect of social media. At least, that could have been the case if the city-state authorities had not released a controversial fake news law last October.

According to Singapore’s Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA), ministers are empowered to order the amendment of online posts that could harm public interest. Failure to comply can be punished with the shutdown of social media pages in Singapore, up to 12 months in prison, and a US$14,000 fine for the author of the falsehood.

Activists and journalists contend the law could further infringe on freedom of expression in Singapore and lead to increasing self-censorship on social media. Significant concerns include the wide degree of discretion placed in every minister’s hands and the considerable leeway of interpretation on what constitutes a falsehood.

As of July 1, POFMA has been used a total of 55 times. The new piece of legislation pursues Singapore’s long-term strategy to control online communication, targeting politically-oriented independent news media and political opposition.

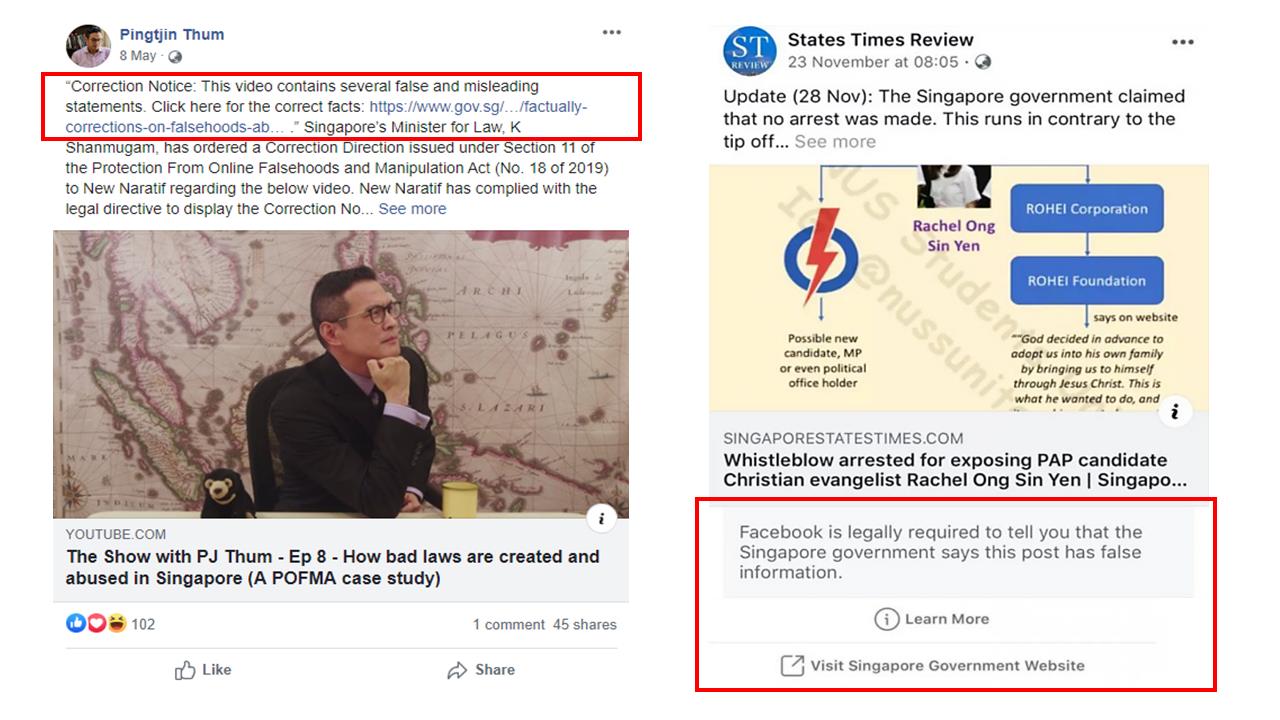

Screengrabs of Pingtjin Thum and the States Times Review Facebook pages, taken July 1, 2020, show POFMA in action.

A Dual Regulatory Regime Under Threat of Harmonization

In contrast with its strict regulation of the media, Singapore initially took a liberal approach to online communication. Under the 1996 amendment to the Broadcasting Act, access to the global internet was subject to very low levels of restriction. Western media outlets and human rights websites were kept online.

This dual regulatory regime did not survive long after the expansion of political blogging. In the 2011 general election, Singapore’s long-term ruling party, the People’s Action Party (PAP), received its lowest number of support (60 percent) since the city-state’s independence. This result was partially attributed to online communications; a survey conducted by Singapore’s Institute of Policy Studies (IPS) reported that during the election, Singaporean constituents increasingly read and relied on alternative online media.

To tackle this alleged threat, in 2013 Singaporean policymakers placed large online media under an individual license regime. The government took a business-friendly approach toward internet regulation by setting profit-oriented websites aside and targeting instead prominent politically-oriented news websites. Online content was subject to a 24 hour notice-and-take-down system, which exposed websites to fines and shutdowns. Moreover, to prevent the development of foreign-subsidized online media such as Malaysian outlet Malaysiakini, the new license system banned websites from receiving grants and loans from foreign foundations and required them to provide full details of funding sources.

By the early 2010s, the booming popularity of social media ramped up the political stakes in online communication. U.S.-imported social media began to be widely used in Singapore and the internet audience extended to average citizens. The previous regulatory regime became toothless, considering that social media outlets do not act like usual content hosting platforms.

POFMA, a Calibrated Response to Social Media Rise

POFMA was proposed in 2017 as a solution to tackle misinformation on social media. Yet, contrary to the stated objective of curbing falsehoods, the fake news law actually follows the same strategy of the previous online communication legislation — that is to say curbing politically-oriented voices on the internet.

According to public data released by the agency in charge of POFMA administration and computed into a database by the website POFMA’ed, the main bulk of orders issued under the fake news law aim at political-oriented nongovernmental forces – around two-thirds of the orders involve independent online media and one-quarter opposition politicians or activists. Less than 12 percent concerns ordinary social network users. For the minister for communications and information, this incongruity is the result of “an unfortunate convergence or coincidence.”

Around 85 percent of flagged posts cover negative portrayals of the government’s moves or policies, touching on hot topics in the political debate, such as mismanagement of public funds, corruption, as well as discrimination against Singaporeans in favor of foreigners. Lately, criticism of the government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic was also targeted.

As to the allegedly false or misleading nature of social media posts, most orders tackle modest inaccuracies, which do not undermine whole arguments. A few more cases include claims difficult to demonstrate due to a lack of public information. For instance, a recurrent bone of contention is the independence of Temasek Holdings, a sovereign wealth fund owned by the Government of Singapore and headed by the current prime minister’s wife. Only a few posts contain manifest and potentially harmful misinformation, like those revolving around the spread of COVID-19.

To pursue the clampdown on politically-oriented and nongovernmental internet voices, Singapore adapted stifling methods to social media.

Authorities can order the closure of a social media page after the publication of a series of falsehoods. The Australia-based Singapore-focused news website the States Times Review has been for now the prime target of this measure. The number of Facebook followers crumbled from 57,000 to 3,000 after four successive shutdowns of related Facebook pages.

POFMA also offers authorities a way to undercut the funding of independent media. Websites operators can be barred from generating revenue from donations, advertising, and subscriptions. In a context of severe financial constraints for politically-oriented news websites, this measure can wipe out revenues for independent online media. For now, this measure has been implemented four times, targeting Facebook pages of the States Times Review.

POFMA also boosts active governmental interaction with social media users. By forcing platforms to insert a contradictory statement at the top of a post, authorities engage into the online conversation with media users to support their views. Attention is diverted to the official interpretation, which is further endorsed by traditional news outlets.

Moreover, by targeting minor inaccuracies within a broad argument, POFMA seeks to discredit opposition and undermine the reliability of alternative news media. This modus operandi particularly threatens independent newsrooms as they struggle to maintain high editorial and fact-checking standards. Small inaccuracies that might result become choice prey for a system that boasts about its nonpartisanship.

POFMA is also a tool to pressure internet intermediaries to increase moderation of content to the government’s interests. Despite initial expressions of concern, Facebook, YouTube, and Singapore-based discussion forum Hardware Zone have all eventually complied with the regulation.

One of the most salient impacts of the law on information intermediaries is Google’s decision to stop running political ads in Singapore. Under POFMA’s code of practice for online political ads, internet intermediaries have to enforce myriad rules, including maintaining a large information record about the commissioner of the advertisement.

These requirements can be regarded as necessary because they emphasize transparency on social media. Yet, in Singapore, they worsen the asymmetric playing field between the incumbent party and the opposition. As the Singapore Democratic Party’s chairman pointed out in a letter to Google’s CEO, social media were one of the only nonrestrained areas of public discussion in Singapore.

Singapore’s general election is just days away. With the COVID-19 outbreak in the background and POFMA at the cornerstone of the government’s online communication strategy, it is very unlikely that the PAP’s half-a-century of dominance on Singapore politics will take a hit in the polls.

Singapore’s ambassador to the United States provided a written response to this article here.

Paul Meyer is a freelance writer and analyst for the Asia-Pacific region. He holds an MA in Asian politics from SOAS University, London.