One of the cascading effects of the COVID-19 pandemic has been its impact on democracies. Some countries have pushed ahead with elections — Sri Lanka, for example, just held their already postponed legislative elections on August 5. Days before that, however, Hong Kong, announced it would postpone its Legislative Council elections by a year, citing the impact of COVID-19.

Health and safety concerns remain as dominant factor in deciding whether or not elections should be conducted during the pandemic. As International IDEA’s Global Overview on the impact of COVID-19 on elections shows, two in three countries scheduled to hold elections in 2020 have decided to postpone them. Among more than 50 countries that have gone ahead to hold elections during the pandemic, nine of them are in Asia. This article looks at four: Mongolia, Malaysia, Japan, and Singapore.

These four countries held elections of varying levels and therefore, magnitudes over a three-week span from late June to early July: Mongolia held their parliamentary elections on June 24; followed by a State Assembly by-election on July 4 in Pahang, Malaysia; a gubernatorial election in Tokyo, Japan on July 5; and finally, the parliamentary elections in Singapore on July 10. While these elections are not the same in scope, it is still interesting to examine them and compare how they were conducted, given the similar threats the pandemic poses for the health and safety of voters and election officials alike.

As International IDEA’s “Elections and COVID-19” Technical Paper illustrated, the spread of communicable diseases such as COVID-19 has implications on the timing and administration of elections. Even though the number of cases may be low, the spread of COVID-19 is always something to be cautious of given instances of resurgence in a number of countries. Consequently, “electoral management bodies (EMBs) must identify and assess the feasibility of implementing any new requirements without compromising the integrity or legitimacy of an election.” Therefore, any election, large or small, taking place during the pandemic must take preventive and mitigating measures to avoid spreading the disease further through the electoral process, which typically involves the interaction of hundreds or thousands of people in confined areas.

The caveat that requires any COVID-19 election not to compromise the integrity or legitimacy of an election, as the Technical Paper suggested, is a key consideration for whether an election should proceed or be postponed. International IDEA considers that the pandemic brings three major constraints to elections: restrictions on freedom of movement and assembly; health-related risks for voters and officials; and operational complications and delays. As such, there are several challenges for the integrity of elections to be managed under COVID-19, including imitations on campaigning; limitations on voter access; impediments to the transparency of the electoral process; risks for the legitimacy of the outcome of the elections; and added financial and administrative pressures.

Limitations on Campaigning

By virtue of the physical distancing requirements during the pandemic, election campaigns cannot be conducted as they used to be. As explained in my previous commentary on the lead-up to the Mongolian elections, the Mongolian government’s Resolution #188, 2020 encouraged meetings to be conducted online, but if online meetings were not possible, the regulations enforced measures and safeguards such as safe distancing, body temperature checks, strict ventilation, sanitization of the vicinity, and mask wearing that had to be ensured by the campaign organizers.

A similar approach was taken by Singapore, leading to the ruling party’s decision to hold the traditional “Fullerton Rally” online, which some say does not have the same flare. Unlike Mongolia, campaign rallies were banned altogether in Singapore and Malaysia. The latter initially banned door-to-door canvassing, but later allowed it with strict health and safety protocols, such as no handshaking and a limit of three participants at any given time. By contrast, election rallies went ahead in more or less the same way as usual in Tokyo’s gubernatorial election in Japan.

Limitations on Voter Access

The fear of spreading the disease through the voting process naturally inhibits the opportunity for COVID-19 patients to cast their votes, given their need to be isolated. Indeed, healthy but vulnerable voters — such as those aged 65 and above as well as those on the lower rungs of the social ladder — are also at great risk. The South Korean elections gave the example of establishing special polling stations for these patients, where voting officials employed extra safety precautions. Singapore followed suit by also establishing such special polling stations and by reserving the first four voting hours for the elderly, with mixed results. With very few active COVID-19 cases during the elections, Mongolia did not establish such polling stations, but put in place a specific protocol in case a symptomatic voter was detected upon entry to a polling station, whereby they would isolated by health officials immediately. Malaysia had a similar procedure to Mongolia in place.

One notable lesson from the South Korean elections was the fact that almost half of their overseas voters were not able to vote due to restrictions on movement imposed by their host countries given the severity of the outbreak there. Voting was due to take place in 166 South Korean missions abroad, but it was suspended in 91 of them. For Singapore, however, even under normal circumstances, overseas voting is only conducted in 10 diplomatic missions abroad, so, this COVID-19 election was no different. This limitation led to some Singaporean citizens living overseas to call for the need to provide for more polling stations and for the adoption of additional special voting arrangements, such as postal and/or online voting. Whatever the number of disenfranchised overseas voters is, this is not a minor issue from the perspective of guaranteeing the fulfillment of basic civil and political rights.

Impediments on Transparency

Conventionally, elections are monitored by domestic and international observer groups to ensure the processes are lawful and meet the requirements for an election conducted with integrity. For COVID-19 elections, the situation could be different. International travel restrictions have prevented full-scale election observation missions from being conducted. For domestic observers, the need for physical distancing is an inevitable inhibitor from closely following voting and counting processes.

These have not, however, diminished the spirits and determination of an observer group in Mongolia consisting of young people under the “Coalition for Fair Elections.” Prior to election day, they protested the limitations imposed by officials in 30 polling stations, who would only allow them to observe for two to four hours out of the 14-hour voting period. In the end, 23 of the polling stations relented and allowed observers to stay the entire time.

In Malaysia, restrictions on observers do exist, but not so much on election day itself. “The number of observers allowed was greatly restricted for all processes up till the polling day. For polling day, other than the usual mask and contact tracing recording, [there were] no restrictions,” said Thomas Fann, chairperson of Bersih 2.0, a leading civil society group.

Risks for Legitimacy

The legitimacy of elections is most often measured through the level of voter turnout in a given election. This is the number of voters out of the total number of registered voters that have come out to cast their votes. The lower the turnout, the less legitimate the results, particularly if the turnout is less than 50 percent. This has been one of the principal worries of elections held during the pandemic, given the physical distancing requirements and the questionable confidence of voters in safely leaving their homes to go to polling stations.

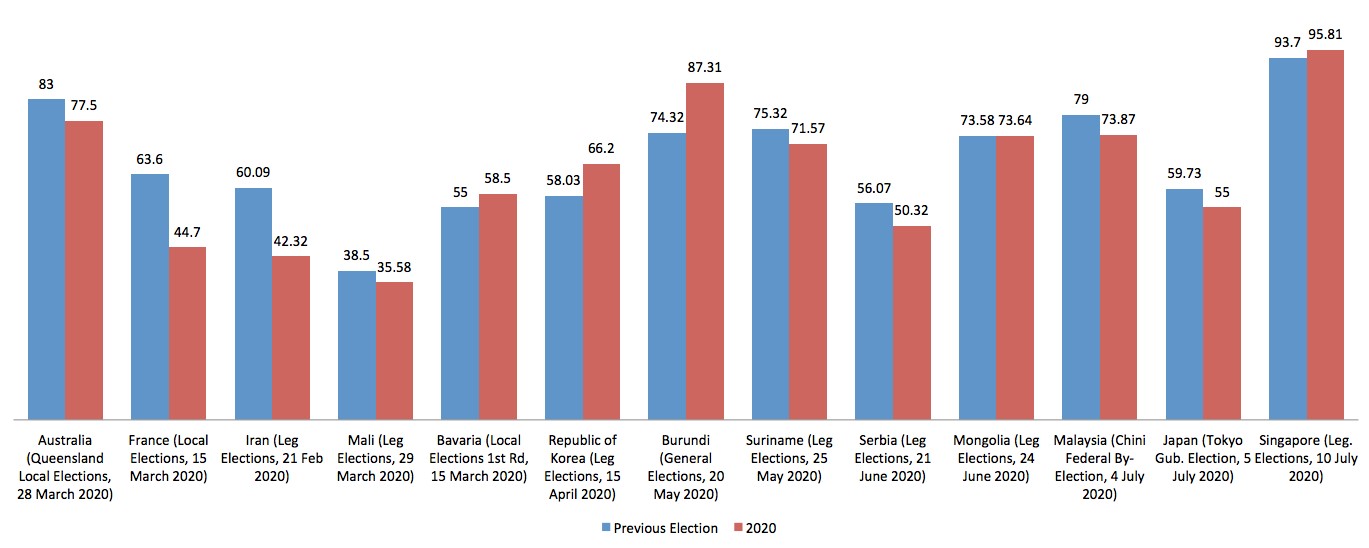

Additional voting arrangements, such as postal voting and early voting, have been used in Queensland (Australia), Bavaria (Germany) and South Korea to maintain a high level of voter turnout compared to previous elections. However, no matter where, the majority of voters are still casting their votes in person at polling stations. As can be seen from Figure 1 below, there is no clear pattern on voter turnout. Each context seems to be influenced by multiple variable factors.

Figure 1. Voter turnout in notable COVID-19 elections since February 2020. (Source: International IDEA Voter Turnout Database and other sources)

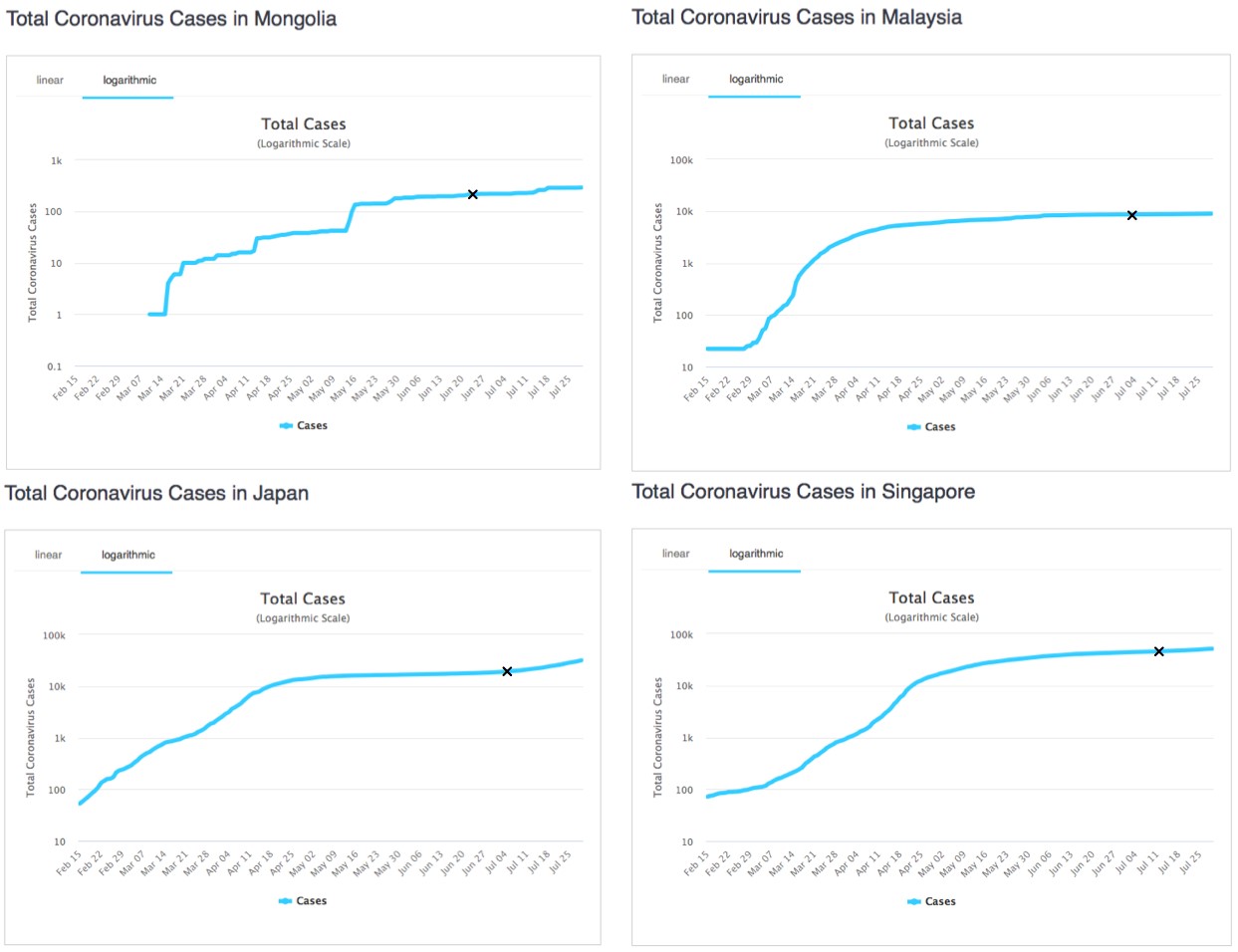

An important factor to consider is the severity of the pandemic in the country at the time of the election. One way of determining that is by examining the shape of the “curve” at the time when the election took place.

Figure 2. COVID-19 “curves” for select countries that held elections in February-April 2020 with ‘X’ marks showing the position on Election Day. (Source: Worldometers.info; accessed on July 30, 2020)

Figure 2 above shows the COVID-19 total cases graph (using a logarithmic scale) for four notable countries that held elections between February and April 2020. South Korea has been noted as one of the most pivotal examples because turnout was the highest since 1992 and the country by then had the most comprehensive health and safety protocols in place (see International IDEA Technical Paper 2/2020 for more information). However, from the above charts, we can clearly observe that by the time the South Korean elections took place, the curve had already flattened. This is the opposite of Australia, France, and Iran, where at the time of their elections, the curve was on the rise. All these elections suffered considerably lower turnouts (see Figure 1). Noticeably, these three elections were held at the beginning of the pandemic; at that time, postponing elections was perhaps the better decision.

Figure 3 below shows the same curves for the four Asian countries we have been discussing. As per Figure 1, Mongolia and Singapore experienced higher turnouts, while Malaysia and Japan had lower turnouts, albeit not significantly. It should also be noted that the latter two countries had subnational elections, which might have led to some voters staying home and averting the risk. These four elections were held when the curve was flat and as such had less of a negative effect on voter confidence and willingness to leave their homes. It is therefore advisable to avoid holding elections while the curve is on a steep rise, like what Japan and Australia are experiencing today. This requires decision makers to predict the future; through models created by epidemiologists, simulations can be done to help make informed decisions.

Figure 3. COVID-19 “curves” for the four Asian countries that recently held elections with ‘X’ marks showing the position on Election Day (Source: Worldometers.info; accessed on July 30, 2020)

Added Financial and Administrative Pressures

From what we have seen, higher costs in organizing elections during the pandemic are noticeable. Equipment such as gloves, face shields, hand sanitizers, and disinfectants had not been on customary lists of electoral materials; not significantly at least. Malaysia and Singapore decided to establish additional polling stations to reduce crowding, which did come at a cost. Of the four highlighted Asian countries, all of them are either middle- or high-income countries according to the World Bank. Therefore, in theory, these added costs are affordable. However, the president of Mongolia did suggest postponing the elections to save money for fighting the pandemic and to prepare the county for a possible recession.

How about the financial effects upon political parties and candidates? One can argue that the cost of campaigning in COVID-19 elections is less due to lack of rallies, reduced face-to-face interactions, and the shift to online campaigns. However, it can also be argued that the cost simply shifts from offline to online campaign activities. Australian mining magnate Clive Palmer famously spent more than 50 million Australian dollars (US$35 million) on media advertising for his own political party – including on the internet – during the 2019 general elections. Whether or not COVID-19 elections reduce campaign spending is relative to how much money election contestants are willing to spend. Clearly, if “offline” campaigns are restricted, campaigning, along with its spending, will simply shift online. Campaign costs can only be reduced by regulation, such as limitations on expenditures and materials, and its effective enforcement.

Organizing these measures present additional administrative burden upon the electoral management bodies (EMBs), too. More equipment will need to be procured and distributed. More polling officials need to be recruited and trained should more polling stations are to be established. One novel idea was to invite voters to cast their votes in accordance with specific time slots throughout the day, which, to the best of my knowledge, was first proposed by the Election Commission of Malaysia in early May. The idea was eventually followed by Singapore’s Elections Department, which allocated the morning of election day from 8:00 to 12:00 for voters aged 65 years and above. However, coupled with the need for every voter to put their gloves on upon entering the polling station, this led to long queues in the afternoon and evening. Consequently, voting had to be extended for two hours, which was initially controversial. Such a problem may have been avoided had early voting some time prior to election day been afforded to all voters like in South Korea, thus reducing the burden of election day, but this also comes at an additional cost.

Conclusion

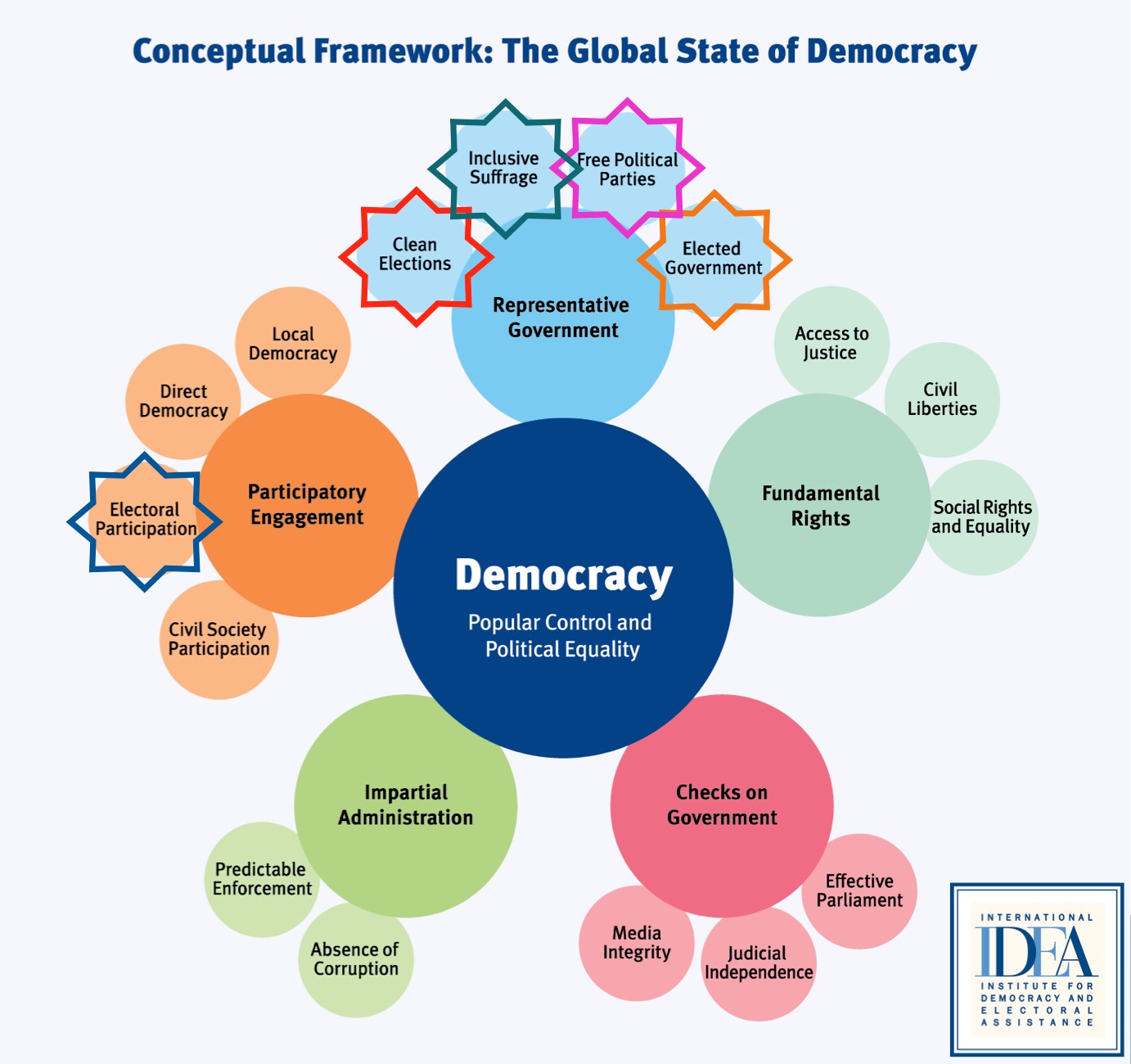

As Figure 4 shows, based on International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices, COVID-19 elections may affect the quality of democracy in five areas. COVID-19 elections may: affect electoral participation, i.e. voter turnout; challenge the cleanliness of the elections, particularly in its administration; affect the participation of certain voters, i.e. those overseas and those who are vulnerable or sick; affect the way political parties operate in the campaign period, i.e. no rallies allowed; and affect the legitimacy of the result through low voter turnout and state emergency situations.

Figure 4. Attributes of International IDEA’s Global State of Democracy Indices that are affected when elections are held during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Asian EMBs are adapting to the “new normal” of conducting elections. While the aforementioned examples show that it is possible to hold elections, there are compromises to reach and high costs to pay. Democracies need to stay vigilant in ensuring that universal franchise, transparency, and legitimacy are not hampered. The challenges faced, as elaborated above, must be well understood and addressed. Authorities should allow some time for that.

This article has been updated to reflect that Malaysia did allow door-to-door canvassing after an initial ban.

Adhy Aman is a Senior Programme Manager (Asia and the Pacific) and Country Programme Manager for Fiji, Malaysia and Mongolia at the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA).