Every day this week, Almaty judges, a slate of cops-cum-witnesses, and lawyers have logged into Zoom to hear criminal proceedings against activist Asya Tulesova. Tulesova – who has been politically and civically active in Almaty for several years – was arrested in June for “insulting a police officer” and “violence against the police,” charges for which she faces three years in prison.

On August 5, quite a crowd showed up to support Tulesova, both in virtual and physical senses. More than 600 people tuned in to watch the court proceedings – far more than could have fit in the Medeu district courthouse – while a sizable crowd chanted, “Bostandyk, let her go!” on the building’s steps. Online, some of the observers changed their avatars to tiny quilt squares; outside, a few protesters held posters with traditional slogans, but others held quilted pillowcases and pieces of paper designed to mimic the patterns of traditional Kazakh quilting.

The quilt – körpe in Kazakh – is quickly becoming the symbol of the moment, but at a deeper level it binds the digital and real-world forms of participation in support of Tulesova specifically and a freer Kazakhstan more broadly. The boundary between virtual and “real” forms of civil society, political engagement, and justice were never as neatly cleaved as social scientists have theorized, but Tulesova’s trial and the movement to free her are an important example of how the two modalities interact to serve broader social and political goals.

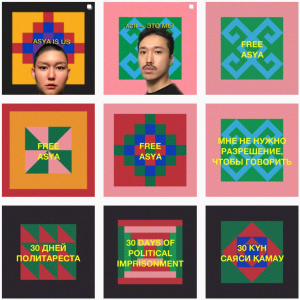

Aisha Jandosova, Irina Mednikova, Jeff Yoo Warren and Kuat Abeshev – friends of Tulesova’s, and activists in their own right – organized the social media project Protest Körpe to draw attention to Asya’s arrest. They invited supporters to create quilt squares with slogans about Tulesova and the freedom of assembly in Kazakhstan; when users posted their images to Instagram – and it’s important that it’s Instagram, given the platform’s design – using a unified hashtag, they created a sort of “newsfeed quilt.”

In an interview with KZ.MEDIA, the organizers cited Aram Han Sifuentes’s quilted protest banners and the AIDS Memorial Quilt as inspiration. Other examples of quilts as collective memorial and political projects abound worldwide. The Tribute to the Disappeared Virtual Memorial Quilt drew attention to 43 missing students from a college in southwestern Mexico; Rohingya refugees collaborated on a quilt as a way to process trauma while preserving a record of the horrors they experienced in Myanmar; the African American Quilters of Baltimore have worked for years to build the Monument Quilt, stitching stories of rape and abuse onto red fabric.

Each quilt serves a dual purpose: The work of creating the quilt offers a sense of agency to those whose stories have been ignored, and the finished product hangs in public, demanding society’s attention and a response from authorities.

A similar dynamic is at play with Protest Körpe. The results of various actions – getting several hundred people to make virtual quilt squares, for example – demand attention from authorities, but Protest Körpe’s organizers told The Diplomat that they are also hoping to cultivate a different sense of civic belonging in Kazakhstan. “We want to shift the discourse from a passive ‘I am against…’ to ‘I am for…’ in the process of dreaming up a freer and more just Kazakhstan,” they said.

Skeptics of digital activism say that virtual civil society is not a substitute for “real” organizations, and that participating in virtual movements – clicking “like” on a campaign, adding a filter to one’s profile picture – are nothing more than “slacktivism,” giving people a feel-good sense of having participated that cannot ultimately scale up to pressure authorities to change.

While the virtual quilt is visually interesting, it’s ultimately more than an aesthetic gimmick.

“Like a quraq körpe,” the organizers wrote in an early Instagram post. “Civic activism and protection of our rights depend on the voices and contributions of each of us.” Indeed, quilting is an apt metaphor for collective action, especially in contexts where mass gatherings – the traditional way political scientists think about successful social movements – are impossible, either prohibited by government decree or dangerous because of the pandemic.

Diana Fu, an associate professor at the University of Toronto, proposed the concept of “disguised collective action” to describe mobilizational strategies that get around top-down restrictions on public gathering and organized challenges to state power. On the surface, these activities look like individual action – people who are frustrated with the system write letters and appeals to register their problem – but just below, Fu finds that this atomized approach is a conscious attempt to get around restriction of mass gatherings and organized opposition.

Protest Körpe is doing something similar. In addition to the hashtag quilt, they’ve coordinated mass appeals to Kazakhstani authorities on behalf of Tulesova. From July 27 to August 1, they oversaw a campaign to activate “pressure mechanisms on authorities” through petitions and appeals.

The organizers consulted Google as well as local lawyers and human rights activists to figure out, “Who in our country – even just on paper – should be defending our rights? Who do we have the right to contact?” They decided on Kazakhstan’s Human Rights Commissioner, the city court, and the president. Their first step to get in touch with Kazakh President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev was through a petition – signed by 4,000 people – and then more directly, by tagging him on Twitter and Instagram and using the e-governance page of his website.

What’s particularly striking about this initiative is how Protest Körpe is demanding a free and fair trial through formal government channels. While the feature for a “virtual appointment” on Tokayev’s website might be criticized as nothing more than window dressing, Protest Körpe has basically forced the regime into a position to intervene on behalf of Tulesova or admit the channel for communication is a farce.

Oftentimes, scholars who study Eurasia emphasize the divide between “official” civil society that has registered its operations with the state, which provides access to resources and relative safety from oppression but at the cost of self-censorship and limited room for critique, and “unofficial” organizations that make up the so-called genuine opposition. These groups exist outside the formal bureaucracy of the state, which makes them vulnerable to targeting but lets them operate without having “sold out.” Just like Protest Körpe is working to bridge the gap between digital and physical forms of civic engagement, the movement shows that this siloing of non-governmental organizations is also analytic deadweight.

Tulesova’s trial has not yet finished; although decisions for those arrested the same day or in similar contexts don’t paint an optimistic picture for her, the sophistication of Protest Körpe’s strategy and engagement show that civil society in Kazakhstan is growing teeth.