Insurgents in Thailand likely use maritime transit routes for drug smuggling and small arms trafficking, which may then help finance their operations and provide arms and ammunition for their members. Although Thailand has dedicated resources to improving law enforcement efforts, gaps in maritime domain awareness may provide opportunities for insurgents to move covertly through coastal waters in both the Andaman Sea and Gulf of Thailand.

Patterns in the use of improvised explosive devices by insurgents in Thailand suggest the availability of resources dictate their levels of activity. As illustrated in Stable Seas’ “Violence at Sea: How Terrorists, Insurgents, and Other Extremists Exploit the Maritime Domain,” the maritime domain can significantly increase the ability of insurgents to finance and supply these land-based operations. By placing renewed emphasis on maritime security in the waters around Thailand, the government can help stem the flow of resources to violent non-state actors.

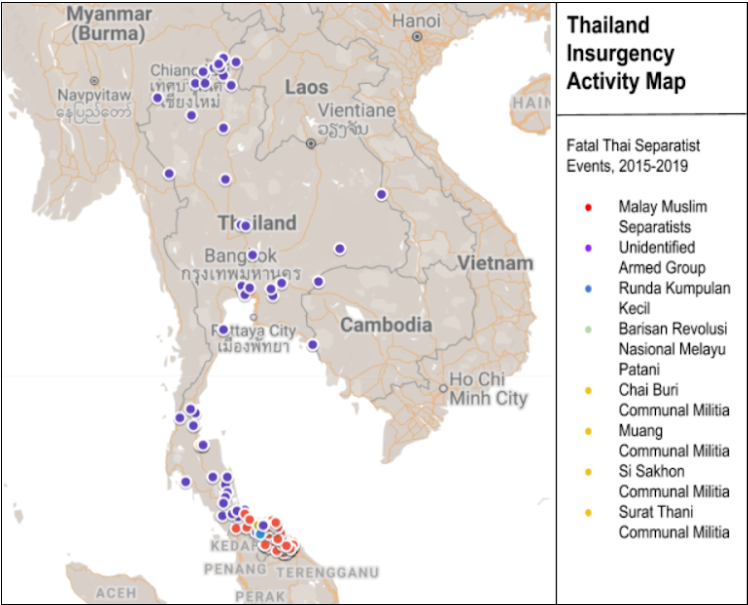

Data Source: Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED)

The Separatist Organizations in Thailand

The insurgency in southern Thailand is divided into several national liberation movements. In 2015, the Majlis Syura Patani, commonly referred to as the MARA Patani, was formed as an umbrella organization to facilitate peace negotiations with Thailand’s central government. Movements represented by MARA Patani include Patani United Liberation Organisation (PULO), Barisan Islam Pembebasan Patani (Islamic Liberation Front of Patani, BIPP), and Gerakan Mujahidin Islam Patani (Patani Islamic Mujahidin Movement, GMIP).

Not all liberation fronts, however, have aligned themselves with MARA Patani. The Barisan Revolusi Nasional (BRN) is currently the largest insurgent group but has not directly participated in the ongoing peace process between MARA Patani and Thailand’s central government. The lack of cohesion between insurgency groups has made progress in obtaining long-term peace difficult, but attempts to bring all parties to the negotiation table continue. Until these groups reconcile with the central government, they are likely to continue to take advantage of the maritime space in three primary ways.

How Insurgents Exploit the Sea: Arms Trafficking, Drug Smuggling, and the Transportation of Extremists

The long-lasting insurgency in southern Thailand has created a strong market for the illicit trading of small arms and light weapons (SALW). Informants have consistently indicated that Thai insurgents are involved in the buying, selling, and smuggling of SALW. Much of the SALW in the region likely originated in Cambodia before being trafficked into Thailand and the rest of the region via land and sea. The weapons are frequently sourced from Cambodian civil-war stockpiles or transited through Cambodia from China.

Involvement in arms trafficking would provide insurgents with a ready supply of arms and ammunition and create an additional source of revenue for insurgents, who sell surplus weapons to militant organizations in Southeast Asia primarily via agents in neighboring Malaysia. Law Enforcement agencies report shipments of SALW being trafficked from Thailand to Malaysia through the waters of Kuala Sepetang, Lumut, and Kuala Gula, often under the guise of fishing vessels. Thai fishing vessels have also been used to smuggle subsidized Malaysian fuel into Thailand to illegally generate profits for Thai insurgents.

While claims by the government that the insurgents are the main contributors to drug trafficking in Thailand remain unproven, statistics suggest insurgents may be involved in drug trafficking as another means of generating revenue. According to data collected by Thailand’s Office of Narcotics Control Board, indictments associated with drugs are consistently higher in the three southern provinces in Thailand when compared to the rest of the country. The “Stable Seas: Bay of Bengal” maritime security report points to the drugs, including the local methamphetamine, yaba, and heroin, flowing primarily from production centers in the Golden Triangle located in the tri-border area between Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar. Facilitating the movement of drugs into Southeast Asia provides access to a lucrative illicit business opportunity. The presence of several maritime routes, in addition to numerous land-based routes, increases the adaptability of illicit actors when attempting to circumvent government patrols. Although evidence of insurgents in drug trafficking operations is primarily circumstantial, their many years of experience in evading border security would give them the opportunity to raise funds by acting as protection and guides for traffickers.

The maritime domain also connects insurgents in Thailand with foreign militants looking to join international Islamic movements. While Thai insurgencies in the predominantly Muslim south are driven mainly by a separatist ideology, unrest in the broader region makes the area a tempting destination for foreign Islamic extremists looking to become involved in militant groups in Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines. Thailand’s maritime borders into these archipelagos and the existence of well traveled trading routes through the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea make Thailand an attractive staging point for entry into other states in Southeast Asia. Arrests have been made in Thailand of Hezbollah members, for instance, after law enforcement foiled their attempt to attack Israeli tourists.

Involuntary human trafficking and smuggling of migrants across the Thailand-Malaysia border is also well-documented. Not only are the insurgents likely complicit in human smuggling, the unrest caused by insurgents in the border provinces contribute to the ability of criminal syndicates involved in human smuggling to operate in the region with relative impunity. Links between extremist groups in Malaysia and Thailand mean fugitives can flee across the border from Malaysia to Thailand for sanctuary. In May 2017, a leader of a terrorist cell based in Kelantan, Malaysia with weapon smuggling connections to Thailand evaded capture by crossing the border into southern Thailand, likely with the help of local Thai insurgents. The porous maritime borders and various means of transportation creates significant difficulties for government law enforcement agencies in Thailand.

How Has the Government Responded?

Recognizing the importance of cutting off foreign sources of supplies to local insurgents, Thailand has introduced several measures to improve maritime security. Thailand has made an effort to increase its maritime capabilities against non-traditional threats, such as by purchasing more offshore patrol boats. In addition, the Thai Maritime Enforcement Command Center (Thai-MECC), which oversees the the Department of Fisheries, Royal Thai Navy, the Marine Department, the Customs Department, the marine police division, and the Department of Marine and Coastal Resources, was recently restructured to mitigate issues of overlapping jurisdiction and to streamline resource usage when addressing maritime security threats.

The interrelated nature of maritime affairs, a phenomenon described in “Stable Seas: Bay of Bengal,” means this kind of holistic approach is needed to effectively counteract non-traditional maritime threats. While progress has been made, the lack of a dedicated coast guard, which has the specialized skill sets to better deal with non-traditional maritime threats, and inadequate maritime domain awareness could allow insurgents to further exploit the maritime space. Efforts to crack down on insurgent activity in the maritime domain have also been hampered by a roughly $557 million cut to Thailand’s 2020 defense budget as the government shifts funds to support the country’s COVID-19 stimulus package.

Conclusion

The movement of extremists and illicit goods through maritime transit routes could be used to facilitate Thailand’s insurgency in the deep south. Involvement in the smuggling of drugs and SALW has the potential to provide the insurgents with much-needed resources. By working in coordination with other illicit actors, insurgents can move products across both land borders and maritime transit routes to the rest of Southeast Asia. By using the proceeds to support their cause, insurgents in Thailand may be able to prolong the conflict. Reevaluating how Thailand’s maritime law enforcement agencies utilize assets at their disposal can enhance the region’s stability moving forward. Coordinated efforts targeting not only insurgent bases but also supply routes can slowly restrict the movement of resources essential to the continuation of the insurgency.

Michael van Ginkel conducts Indo-Pacific research for the Stable Seas program, which provides innovative research on maritime security issues and organized political violence. He holds a master’s degree in conflict studies and specializes in conflict resolution and peacekeeping operations.