Based on the latest count, over 150 countries worldwide have implemented policies, laws, and constitutional prescriptions to make asset disclosure mandatory for public officials. The anti-corruption impact in many countries has been palpable, as studies have shown how this level of transparency helps investigate, prosecute, and convict the corrupt. Even more powerful, there is evidence that it actually helps dissuades potential corruption. Of course, this effectiveness lies in the ability of governments to properly use asset disclosure rules as part of a broader system to combat corruption. It helps if the people tasked with investigating asset disclosure data are not corrupt themselves, but that is sometimes a luxury not always available. Hence, the only way to be sure is if the data is made available to the public.

In the Philippines, the main anti-corruption agency, the Office of the Ombudsman, recently issued Memorandum Circular No. 1 Series of 2020, which severely constricted public access to public officials’ statement of assets, liabilities, and net worth (SALNs) in their custody. We believe the ombudsman should rethink this unreasonable imposition and we offer here four reasons why SALNs must be made absolutely accessible to the public.

1. It Is Effective in Mitigating Corruption

States parties to the United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) are called to adopt asset declaration and financial disclosure regimes for their public officials. A majority of these countries have responded, even as the details of compliance have been varied. In a sample of 175 countries studied in 2010, 109 countries had some form of disclosure laws for their members of parliament (MPs). But over half of these countries did not make disclosures available to the public in practice. These authors examined the disclosure protocols across countries in greater detail, and they found evidence that “it is public, rather than confidential, disclosure that is associated with lower perceived corruption and better government.” Furthermore, they found that fleshing out the details on “the assets, liabilities, income sources, and conflicts, as opposed to income and wealth levels, is more consistently associated with better government.”

In addition, a corruption report by Omer Gokcecus and Ranjana Mukherjee found evidence that countries with a longer history of asset declaration practices by their officials are associated with much lower corruption as indicated by Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index (CPI). Moreover, Gustavo Vargas and David Schultz constructed an index to measure the relative intensity and extent of financial disclosure measures across countries using World Bank data, and they found evidence that a more extensive financial disclosure system for public sector officials is also associated with lower corruption indicators over time.

2. It Is Consistent With the Right to Privacy

Analysts contend that public disclosure of assets by public officials and their family members need not clash with privacy and data protection laws. These are not absolute rights and legal tradition shows how they can be restricted in an effort to balance public good objectives of promoting good governance while protecting rights.

Specifically, a World Bank analysis noted:

In Wypych v. Poland (October 25, 2005, application no. 2428/05), the European Court of Human Rights rejected the complaint of a local council member in Poland who refused to submit his asset declaration claiming that the obligation to disclose details concerning his financial situation and property portfolio imposed by legislation was in breach of Article 8 of the European Convention of Human Rights. The Court found that the requirement to submit the declaration and its online publication were indeed an interference with the right to privacy, but that it was justified and the comprehensive scope of the information to be submitted was not found to be excessively burdensome.

In addition the court ruled that “the additional obligation to submit information on property, including marital property, can be said to be reasonable in that it is designed to discourage attempts to conceal assets simply by acquiring them using the name of a councilor’s spouse.”

The authors also noted how the European Court of Human Rights supported public financial disclosures via the internet: “[T]he general public has a legitimate interest in ascertaining that local politics are transparent and Internet access to the declarations makes access to such information effective and easy. Without such access, the obligation would have no practical importance or genuine incidence on the degree to which the public is informed about the political process.”

3. It Is a Constitutional Directive

In the Philippines, the submission of a SALN is a constitutional directive. As per Article XI, Section 17 of the 1987 Constitution, “A public officer or employee shall, upon assumption of office and as often thereafter as may be required by law, submit a declaration under oath of his assets, liabilities, and net worth.” The rationale for this prescription is articulated in Section 1, to wit: “Public office is a public trust. Public officers and employees must at all times be accountable to the people, serve them with utmost responsibility, integrity, loyalty, and efficiency, act with patriotism and justice, and lead modest lives.” The SALN is a tool provided by the constitution to the public to make sure public officials meet this standard of public service.

Pertinently, the submission of the SALN is a mandatory statutory requirement as well. As per Section 8 of RA 6713, “Public officials and employees have an obligation to accomplish and submit declarations under oath of, and the public has the right to know, their assets, liabilities, net worth and financial and business interests including those of their spouses and of unmarried children under eighteen (18) years of age living in their households.”

Additionally, the law requires that the SALN shall be made accessible to the public (See Section 8 (C)). But it includes the caveat that “It shall be unlawful for any person to obtain or use any statement filed under this Act for:

- any purpose contrary to morals or public policy; or

- any commercial purpose other than by news and communications media for dissemination to the general public.”

It is worth noting that SALNs are required by law because of the policy of the state “to promote a high standard of ethics in public service” and the command on all public officials to “uphold public interest over personal interest.”

4. Some Philippine Officials Have Much to Explain

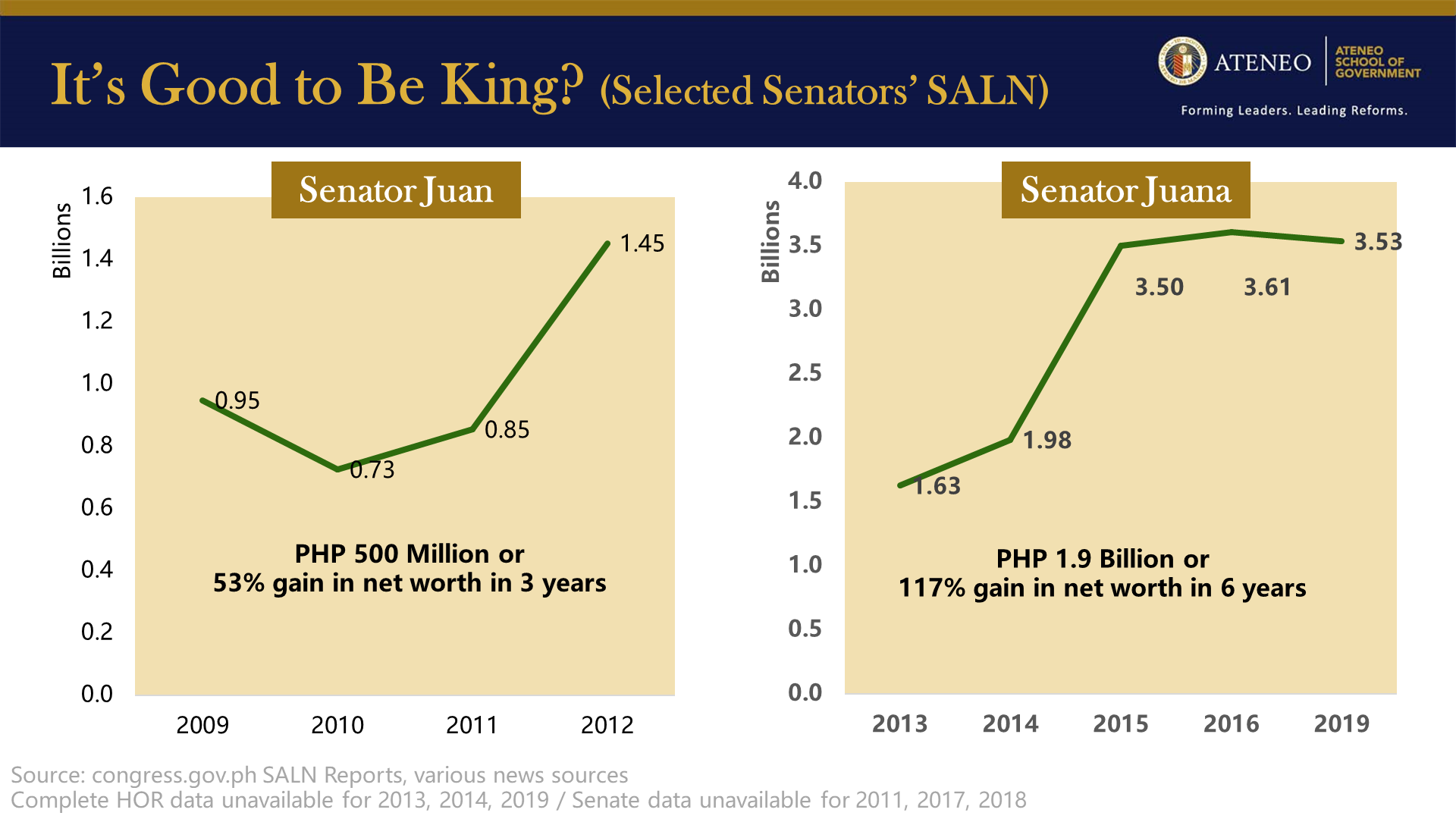

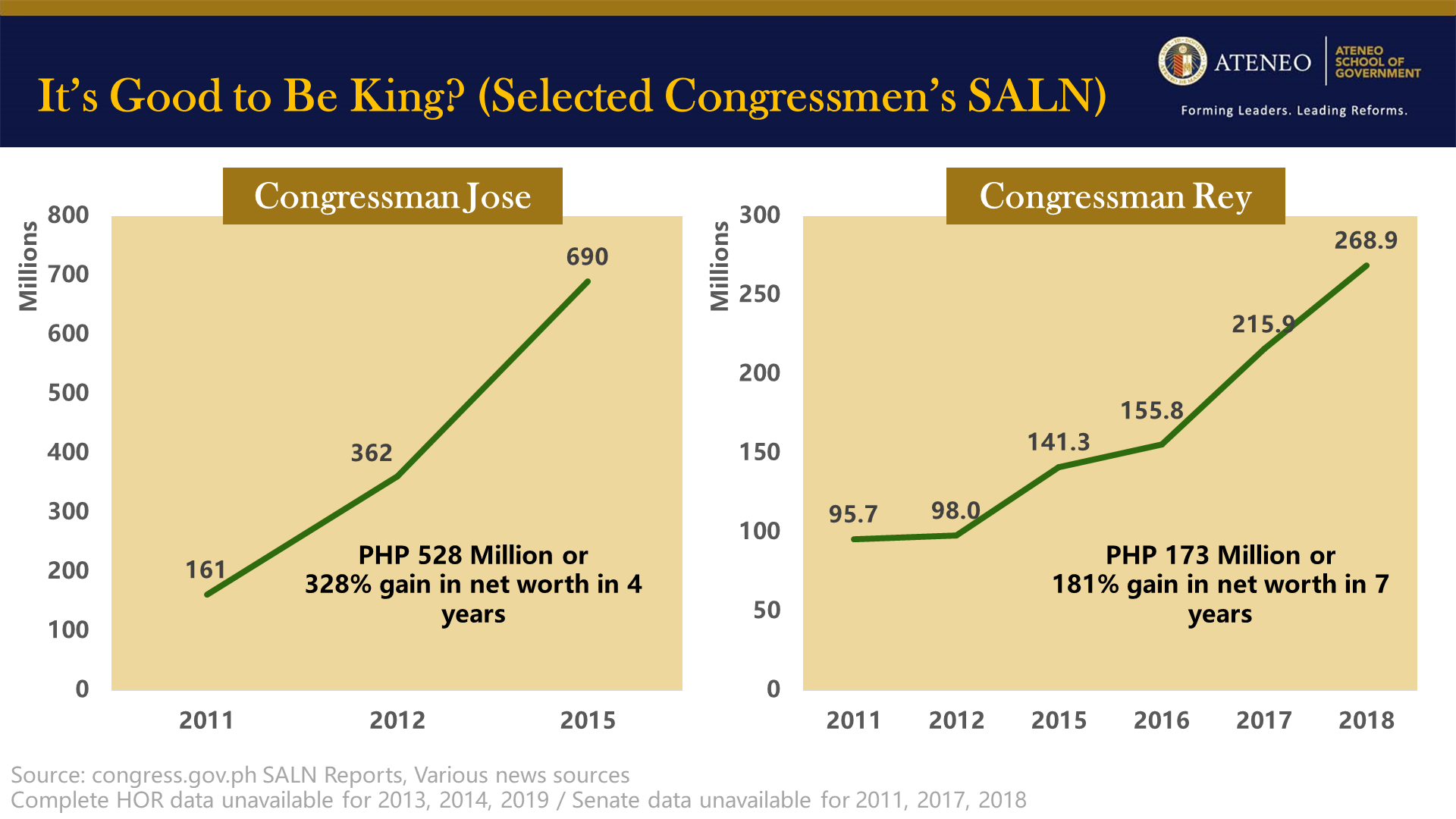

As a final point, it is clear that even with public disclosure of financial assets, many senior Philippine officials have much to explain. In our tracking of publicly available SALNs for legislators, we found evidence of phenomenal growth in wealth for some senators and congressmen while they were serving their terms in office.

One dynastic senator saw his wealth increase by over 500 million Philippine pesos in just three years, while another saw her wealth increase by 1.9 billion pesos in just six years. Among dynastic congressmen whose SALNs we tracked, we saw even more impressive growth rates in wealth, ranging from almost 200 percent to well over 300 percent just in one term (three years). It is not necessarily a problem for wealthy individuals to run for office and try to enter public service. On the other hand, a public official suddenly becoming extraordinarily wealthy while in public office should be a clear anti-corruption red flag. Indeed, it is in this context that meaningful checks-and-balances must be put in place so that positions of power are not abused, and conflict of interest is avoided.

It is worth noting that public officials with policy and regulatory oversight over economic sectors that they themselves (or their families) have a stake in often engage in more subtle forms of corruption. Therefore, it behooves the ombudsman to give a full effort in investigating some of these officials’ phenomenal growth in wealth.

In the final analysis, if such increases in wealth can be properly evaluated in independent and fair reviews, then the purpose of making the SALN data available to the public would have been served.

Ronald U. Mendoza is dean at Ateneo de Manila University’s School of Government.

Michael Yusingco is a non-resident research fellow at the Ateneo School of Government.