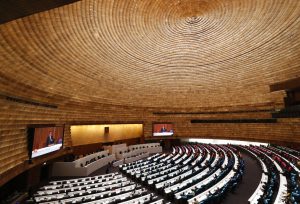

Thailand’s parliament has come out of recess for a special session aimed at addressing simmering pro-democracy protests that have demanded the prime minister’s resignation and aired combustive calls for monarchical reform. The meeting has been convened under Section 165 of the Thai constitution, which states that the government can request a bicameral session to gauge members’ opinions on issues of national importance. The non-voting session of parliament opened on October 26, and is expected to last two days.

At the opening of the session, House Speaker Chuan Leekpai called on parliamentarians and senators to make a concerted effort to find a solution to the political conflict. “I told the MPs they must try to prevent that by cooperating and presenting useful ideas. This is not a censure debate,” he said. That didn’t stop the leader of the opposition Pheu Thai party, the largest single party in parliament, from calling on Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha to step down. “The prime minister is a major obstacle and burden to the country,” Sompong Amornvivat said. “Please resign and everything will end well.”

Student-led protests have taken place periodically since March, and every day since October 14, when demonstrators gathered en masse in the Thai capital. Demonstrators are calling for Prayut to step down and for the drafting of a new, more democratic constitution. Activists have also aired more explosive calls for reforms to curb the powers of the Thai monarchy and King Maha Vajiralongkorn, who spends much of his time at his luxurious aerie in the southern German alps. The latter demand is especially explosive in a country where the palace has long been treated as sacrosanct, and is protected by a harsh lese-majeste law that criminalizes any criticism of it.

Prayut called for the special session after the government’s imposition of a “severe” state of emergency on October 15 failed to curb the demonstrations. “The only way to a lasting solution for all sides that is fair for those on the streets as well as for the many millions who choose not to go on the streets is to discuss and resolve these differences through the parliamentary process,” Prayut said last week. The emergency decree was lifted on October 22.

In September, the Thai parliament was scheduled to vote on six proposed constitutional amendments but instead chose to set up a committee to further consider such proposals. It then recessed until November 1, angering protest leaders.

As the session opened on October 26, anti-government protesters announced a march to the German Embassy in Bangkok, in order to petition officials there about King Vajiralongkorn’s use of powers while on German soil. Earlier this month, Germany’s Foreign Minister Heiko Maas said that the Thai monarch should not be engaging in politics from his Bavarian retreat.

Despite the Thai government’s revocation of the emergency decree, there are significant reasons to doubt the government’s willingness to give ground. For one thing, the government outlined just three topics for discussion during the parliamentary meeting: the risk of COVID-19 spreading at rallies; protesters’ alleged interference with a royal motorcade during the October 14 protest; and various violations of the law by student demonstrators. Given that most of these are thinly disguised criticisms of the protest movement, the session – which is not equipped with the power to legislate – is unlikely to produce anything concrete. The parliament has made it clear that the question of the monarchy will not even be up for discussion.

Neither is King Vajiralongkorn likely to give ground. In a rare gesture, the 68-year-old was this weekend captured on video praising a royalist who held up a poster of the king at an anti-government protest last week. In the video, which was widely circulated on social media, Vajiralongkorn described the man as “Very brave, very brave, very good, thank you.” The rare public comment is a clear sign of royal assent to the self-proclaimed “defenders of the monarchy,” many of them swathed in royal yellow, who have begun to organize pro-monarchy rallies in several Thai cities.

The government’s primary likely intention is to dilute protesters’ demands by directing them into an interminable politico-bureaucratic process, hoping that the demonstrations eventually lose steam and peter out. As a result, the parliamentary session is unlikely to assuage the anger of protest leaders, who view it rightly as an attempt to buy time. All this suggests that Thailand could be set for a protracted period of protest and counter-protest, like the dueling red and yellow shirt rallies that characterized the period between the military coups of 2006 and 2014.

So far, the Prayut administration’s approach seems consistent with that of Thai governments over the decades: improve the appearances of democracy, but only insofar as these do nothing significantly to rearrange prevailing political and economic hierarchies. Given the importance of the monarchy in sacralizing Thailand’s longstanding divides of wealth and power, those in power see little reason for real compromise.