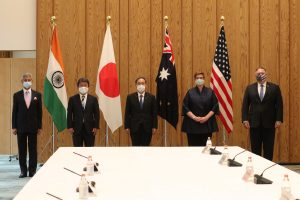

The symbolism of the Quad foreign ministers’ meeting on October 6 could not have been more evident. In the middle of a pandemic, when heavy restrictions have been placed on international travel and many multilateral meetings have been postponed or moved onto virtual platforms, the top diplomats of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States convened in Tokyo for the second Quad foreign ministers’ meeting.

Widely viewed as an arrangement to counter China, the Quad meeting occurred alongside rising concerns among its four members regarding instances of Beijing’s aggressive behavior and questions about its role in the initial stages of the COVID-19 outbreak. Unsurprisingly, China has expressed its disapproval at the formation of such “exclusive cliques” and urged “the relevant countries” not to disrupt regional peace, stability and development.

In some aspects, the Quad ministerial meeting reflected a continuation of their past style of cooperation. The foreign ministers exchanged views on China’s behavior in regional disputes, and agreed to boost cooperation in maritime security, infrastructure building, and cyber matters, among other areas, as well as strengthen collaboration in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. They also discussed ways to advance the Indo-Pacific concept and uphold the rules-based order.

There was no joint statement, and the four countries issued their own read-outs of the meeting. On-record views about China also continued to differ. While U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo called upon the other Quad members to work together against the Chinese Communist Party’s “exploitation, corruption, and coercion” in his opening remarks, his counterparts appeared comparably more circumspect as they emphasized the importance of rules, international law and the peaceful management of disputes in their opening remarks.

There were, however, two “firsts” that stood out. For one, this was the first time that the foreign ministers of the four Quad countries held a standalone meeting. The previous – also the inaugural – meeting of the Quad foreign ministers was conducted on the sidelines of a United Nations General Assembly session in New York in September 2019. Moreover, working-level meetings that involve the four countries have also typically been convened on the sidelines of forums led by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

This approach is starting to change, however, with the pandemic putting a halt to physical ASEAN meetings. Assuming that such large multilateral meetings continue to be out on hold, it is likely that Quad meetings may evolve into standalone events. The four foreign ministers have agreed to convene the ministerial meetings on a regular basis, with the third iteration scheduled for next year. This would certainly cast a shadow over the convening power that ASEAN has traditionally taken pride in, including with meetings – including past Quad gatherings – where ASEAN is not directly involved.

Along with remarks by U.S. officials about potentially institutionalizing or formalizing the arrangement, the trend of standalone Quad meetings would be a concern for ASEAN. To be fair, the read-outs from all four countries following the Quad ministerial meeting reaffirmed their support for ASEAN centrality and mechanisms in the regional architecture. But the loss of ASEAN’s convening power could in the longer term mean a corresponding decline in the importance of ASEAN centrality to the four Quad countries.

This was also the first Quad ministerial meeting – following a senior officials’ meeting in late September – since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, from late March, deputy foreign ministers of the four Quad countries, as well as New Zealand, South Korea, and Vietnam, have been meeting virtually on a regular basis. The composition of this arrangement has led some to dub it the “Quad Plus.”

Discussions at these meetings have thus far focused primarily on responses to COVID-19, but the fact of its existence indicates the possibility for it to develop into a new multilateral arrangement that persists into a post-COVID world. For the United States, for instance, this grouping arguably lays the foundation for its proposed Economic Prosperity Network comprising a network of “trusted partners” that would help to diversify global supply chains.

Although the Quad 2.0 and Quad Plus are relatively nascent platforms, there are parallels with how ASEAN and ASEAN Plus processes operate. Both sets of arrangements have a core group (the four Quad countries and ASEAN respectively), and both have sought to build a second layer of multilateral relations with key partners. It is certainly too early to make any definitive claims about “Quad centrality” in the regional architecture, but the Quad’s construction of relations with external partners would bear watching.

Overall, the Quad’s second ministerial meeting was significant in terms of demonstrating the four countries’ commitment to enhancing cooperation based on shared interests. Looking ahead, the Quad’s evolution would be expected to bring about changes in the regional architecture and, potentially, the role of ASEAN-centric mechanisms in this architecture.

Sarah Teo is research fellow with the Regional Security Architecture Programme at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore.