Last week, Reuters reported that Vietnam’s government had threatened to shut down Facebook in the country if the social media giant refuses to bow to government pressure to censor more local political content on its platform.

According to the report, Facebook complied in April with a government request to significantly increase its censorship of “anti-state” posts for local users. However, the Vietnamese government asked the company again in August to step up its restrictions of critical posts, dangling the threat of a ban.

“They have come back to us and sought to get us to increase the volume of content that we’re restricting in Vietnam,” an anonymous company official told the news agency. “We’ve told them no. That request came with some threats about what might happen if we didn’t.”

Facebook is astoundingly popular in Vietnam. More than 66 million Vietnamese are on the social media platform, giving the country the seventh-largest user base in the world.

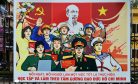

The platform has created a vibrant public sphere outside and beyond the ambit of the ruling Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) and its wooden state media outlets. This has not only given government critics and pro-democracy activists unusual freedom to complain about the government or advocate democratic reforms, in addition to more mundane social media activities. It has also opened up a channel of communication between local users and stridently anti-communist Vietnamese communities in the United States.

But in the last several years, the company has repeatedly censored dissenting posts at the request of the Vietnamese authorities. In April 2017, according to a recent investigation by the Los Angeles Times, Vietnamese officials told a senior Facebook executive that the company must cooperate “more actively and effectively” with government requests to remove content, according to reports in state media. The company subsequently set up an online channel through which the government could report users accused of posting illegal content.

By October of this year, a minister told Vietnam’s parliament that the social media firm was complying with 95 percent of the government’s requests to remove content, up from about 30 percent initially.

Vietnam is not the only country that fears the integrative power of Facebook, and has considered restricting access to it. The Solomon Islands announced recently that it would ban the platform due to a rash of online criticisms of the government. While only Nauru, Iran, North Korea, and China have banned the social network outright, Facebook is facing increasing pressure from governments over its content policies, including threats of new regulations and fines.

Vietnam’s foreign ministry told Reuters that Facebook should abide by local laws and cease “spreading information that violates traditional Vietnamese customs and infringes upon state interests.”

The order illustrates the tension that lies at the heart of Facebook’s business model. On the one hand, Mark Zuckerberg and other senior Facebook officials frequently claim wide-eyed fealty to ideals of freedom and openness. On the other, they preside over a globe-spanning corporate Goliath whose business model is premised on ramping up the volume of content on its platform, the better to push irritating ads on the network’s billions of users.

This makes it clear that Facebook’s aversion to censorship is relative rather than absolute. As the above-cited LA Times investigation showed, the company has been willing to block content that the Vietnamese authorities deem unlawful. Citing internal sources, the Reuters report stated that Facebook earns annual revenue of nearly $1 billion from its operations in Vietnam. This suggests firm limits to how far the company would be willing to go to take a stand for freedom of expression.

Of course, things are just as thorny on the other end of the equation. The Vietnamese government would undoubtedly face huge difficulties in banning Facebook outright. There are the technical challenges, sure – but one would expect that these could be overcome if the political will was present. I’m referring rather to the wave of anger that would no doubt follow any attempt to ban the platform, from a public that is already critical of the government for a number of reasons. This makes it entirely possible that the social media platform could simply call Hanoi’s bluff.

Given the complex calculus facing both sides, the relationship between Facebook the Vietnamese government will likely remain in a state of stable tension. In this state, the two sides – caught between the desire for profit in the one instance, and the fear of political instability in the other – will grope their way slowly toward a lasting modus operandi.