For the past year, Thailand has seen an accelerating cycle of student-led protests that have sought the resignation of the government of Prime Minister Prayut Chan-o-cha and made taboo-shattering calls for restrictions on the power of the Thai monarchy.

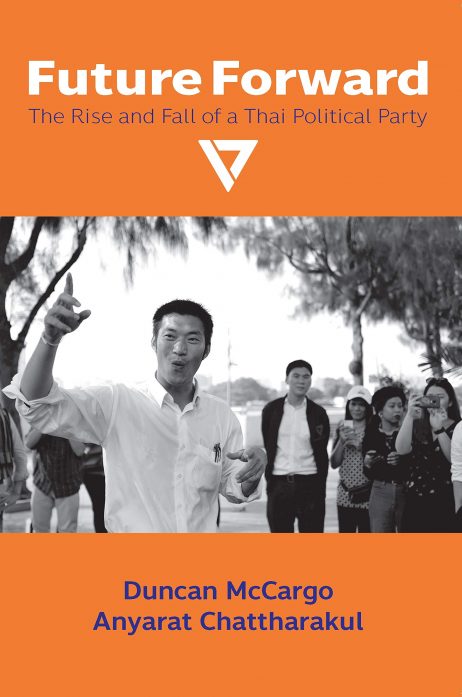

An important precursor to the current ferment was the emergence of Future Forward, an upstart political party led by the 41-year-old autoparts tycoon Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit. With minimal local roots, Future Forward won 81 seats at elections in March 2019 and became the third-largest party in parliament, before a court dissolved it on a technicality in February this year.

In their recently published book “Future Forward: The Rise and Fall of a Thai Political Party” (NIAS Press, 2020), Duncan McCargo and

director of the Nordic Institute of Asian Studies and professor of political science at the University of Copenhagen, and a longtime observer of Thai politics, spoke with The Diplomat’s Southeast Asia Editor Sebastian Strangio about the remarkable rise of the Future Forward Party, and the challenges facing Thailand’s new youth-led protest movement.

The Future Forward Party burst onto Thailand’s political scene in 2018 and quickly made a significant impression, coming in third place in the election in March 2019. How do you explain the party’s success?

Clearly there are a lot of different factors at work here. Perverse though it may sound, Future Forward was actually a major beneficiary of the much-criticized 2017 constitutional set-up and associated electoral system, which was designed to boost medium sized parties (while shrinking large ones). It also benefited from the dissolution of the Thai Raksa Chart Party right before polling day, picking up a number of seats where no other major opposition party was running. But Future Forward’s success also derived from the party’s ability to occupy the center ground: its orange color deliberately appealed both to former ‘yellows’ (conservatives) and former ‘red’ (Thaksin supporters) who had become tired of the country’s 14-year color-coded polarization. It also hinged on a powerful appeal to younger and first time voters, especially through social media messaging, successfully demonstrating that no-name local candidates could be elected to parliament on the basis of national campaigning and branding.

A billionaire outsider who threatens to upend prevailing power structures: from a certain angle, we’ve seen this story before. Do you see any comparisons between Future Forward leader Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit and former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra? Where do the two leaders most obviously differ?

I asked Thanathorn a similar question at a public event at LSE in 2018: Are you seriously telling us Thailand needs another charismatic billionaire to rescue the country from its own political contradictions? This was always the weak point of Future Forward’s messaging: how can a borderline cult of personality solve structural problems generated and perpetuated by personalistic politics? But one important difference is that whatever fuels Thanathorn – and there must be a serious ego behind his modest demeanor – it is clearly not naked self-interest. He is not in politics to make more money for himself; and I do believe that Thanathorn is as ‘genuine’ as any Thai politician I have met. Ukrist Pathmanand and I opened our 2005 book “The Thaksinization of Thailand” by saying we believed Thaksin was a complete pragmatist, whose supposed ‘ideas’ were purely instrumental, and did not merit any serious discussion. That is absolutely not the case with Thanathorn. He passionately believes that Thailand has to change in a progressive direction.

The dissolution of Future Forward in February 2020 seems to have catalyzed the present anti-government protest movement. At the same time, Thanathorn seems to have kept a fairly low-profile during recent demonstrations. How would you characterize the role of Future Forward in the current ferment?

The dissolution of Future Forward in February 2020 seems to have catalyzed the present anti-government protest movement. At the same time, Thanathorn seems to have kept a fairly low-profile during recent demonstrations. How would you characterize the role of Future Forward in the current ferment?

Right, I am quite sure Thanathorn and Future Forward are not “behind” the protests – the student leaders have their own very independent ideas about how to do things. That said, Thanathorn does sometimes show up on the sidelines of the demos – he turned up with most of his family in tow the other day – and remains a respected figure for the students. But ironically he is already too old and too conservative in their eyes to be really significant as a player now. At the same time, Move Forward MPs such as the very outspoken former student activist Rangsiman Rome have played a key role in bailing out the protest leaders, and in using their parliamentary status to try and give the movement some cover and protection.

The most striking thing about the current anti-government movement has been its willingness to identify the monarchy as the central question in Thai politics, and demand that it be placed under constitutional control. What do you think has led so many young Thais to take aim at the unquestionable institution? Why now?

The 2016 royal transition opened up the monarchical institution to much greater scrutiny than before, yet the recent critical turn of the student movement concerning the monarchy has taken most of us by surprise. Future Forward was always extremely careful on this issue, for fear of being tarnished with the label lom jao (anti-royalist), which up to now was the kiss of death for any mainstream Thai politician. The student protests were not initially focused on the royal institution, but on calls for constitutional change. The royal reform theme began only with the 10 demands announced on 10 August at Thammasat University, by what was then a radical fringe element of the student movement. It is an issue made popular by the way young people under 25 – Generation Z, or digital natives – can access information online from sources all over the world. They can easily find out about previously taboo subjects such as the October 6, 1976 massacre or the extent of kingly wealth. Simply put, the new generation of Thais does not feel bound by older notions of deference or hierarchy, and are bold enough to say whatever is on their minds.

At one stage in the book, you and your co-author point to a contradiction within Future Forward, asking whether it was seeking to transform the system from within, or “to bring it crashing down.” Do you see a similar contradiction in the current protest movement? Where do you think the current anti-government energy might lead?

This is very much the problem with the ongoing protests: in the absence of a clear sense of what might replace the current Thai political order, it is hard to see how the students can achieve their goals. Everyone can agree on what they don’t like – but what do they want instead? And how can a “leaderless” movement negotiate with those in power?

Nevertheless, the student have time on their side. They might face setbacks in the short term, but if future generations of Thais feel no obligation to respect kings, generals and other elderly men, it’s not a matter of whether or not the existing power structures start to give way: it’s just a question of when.