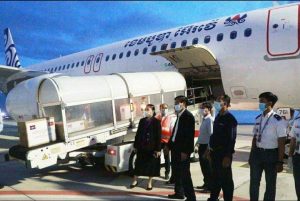

On November 26, Cambodia’s government announced the donation of a cluster of 1.5 million masks and other necessary medical materials to the government of Timor-Leste, to aid it in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic. According to a report in the state media agency Agence Kampuchea Presse, the donation included 1 million facemasks, 10,000 N95 respirators, 10 ventilators, and 1,000 units of hand liquid soap.

The shipment, which arrived in Timor-Leste on December 2, followed similar donations by the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen to Myanmar and Laos. The Cambodian shipments to the two countries consisted of 2 million face masks and other vital supplies of personal protective equipment.

In a November 24 letter to State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi, Hun Sen described the shipment as a sign of the “spirit of our long-standing friendship and solidarity.” “With our collective effort, I strongly believe that we will succeed in the fight against Covid-19, and we will emerge stronger together,” he said in the letter. Two days later, Myanmar’s leader expressed her “deep appreciation” for the Cambodian donation.

What explains the apparent generosity of one of Southeast Asia’s poorest nations, one that has itself been the recipient of vital aid and supplies to fight COVID-19? The most obvious answer is that Cambodia has largely been spared the worst of the pandemic, and so has surplus materials to pass onto more needy neighbors.

Through a mixture of culture, luck, and effective government restrictions, Cambodia is among the countries least impacted by the coronavirus. As of December 2, the country had reported just 329 cases– most of them imported – and no deaths. It stands to reason that the government would help neighboring countries, in the expectation of similar support if and when it experiences its own outbreak.

On another level, Phnom Penh’s “mask diplomacy” would also seem to reflect the ambitions and pretensions of Cambodia’s leader.

Domestically, such donations, publicized widely via Hun Sen’s Facebook page and the various state-run and state-aligned media outlets, serve to burnish the meritorious image that is central to Hun Sen’s public persona. For years, the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has legitimized itself through the dispensing of charity and patronage to the population, often funded from the personal fortunes of Hun Sen, senior CPP figures, and merit-making tycoons.

The extension of the merit-making charity across borders is only a logical extension of this scheme. In 2013, Hun Sen even funded the opening of a school in the central African nation of Mali, a carbon copy of the thousands across Cambodia that bear his initials.

It also may function as an expression of the government’s pride that after decades of conflict and poverty it is no longer simply a recipient of foreign assistance, but a provider of it. Another much-touted example is Cambodia’s contribution to United Nations peacekeeping missions, after the country itself was the target of a massive U.N. mission in 1992-93.

It remains unclear the provenance of the materials donated by the Cambodian government, which is to say, whether the country is simply repackaging aid that it has received from other sources, or whether the materials were purchased by the government.

In any case, the country may soon not have the luxury of such generosity.

On November 29, the country recorded its first cases of community transmission after six people tested positive for COVID-19, triggering a mini-outbreak that led Hun Sen to order a ban on wedding parties and gatherings of more than 20 people. Describing it as the “most critical moment” for the country, the Cambodian leader also ordered the distribution of 2 million face masks in Phnom Penh and the town of Siem Reap in the west of the country. If the infections spread much further, it could bring Phnom Penh’s regional COVID-19 charm offensive to a rapid halt.