An acquaintance of mine lamented recently that some new friends of hers were palpably disappointed when they were told that she was “half-Chinese.” Their words to her were to this effect: “Oh, I thought you were half-Japanese. I like the Japanese.” In this small but intriguing exchange between individuals, we gain some insight into how public attitudes toward cultures and societies are influenced by geopolitics. Since the end of World War II, and with the exception of the 1980s when Japan’s economic rise was seen as a threat, the American public has on the whole maintained a highly positive view of Japan’s culture, politics, and society. On the contrary, the public perception of China has become increasingly negative over time, and anti-China sentiment has been on a sharp rise since the COVID-19 pandemic. What is often overlooked, however, is how public perceptions of Japan and China serve as counterpoints to one another, in turn undermining trust in China’s leaders while giving undue credit to Japan’s – to the detriment of regional stability.

Over the years, my students have helped me understand that the American public’s positive perception of Japan rests mostly on ignorance. I have heard the following question at the end of every semester teaching a course that focuses on the historical interactions between China, Japan, and the Koreas, “Why did we not know about the Asian Holocaust until now?” Many have lamented that their high school world history curriculum glosses over or entirely overlooks this dark chapter of world history, whitewashing the atrocities committed by the Japanese colonial administration in Korea and the Japanese Imperial Army during the Pacific War in particular.

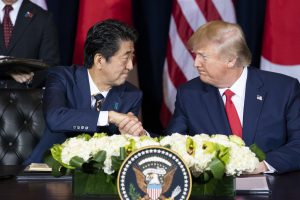

It is no wonder, then, that few managed to connect the dots when then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe rushed to meet incoming President Donald Trump in his gold-gilded apartment in New York City back in 2016 – the first world leader to do so. With Abe hailed by Steve Bannon as “Trump before Trump,” U.S.-Japan relations seemed stronger than ever. This was, for the most part, seen in a positive light. Most Americans are given to understand that Japan has been one of our most important allies in the region, and that with the rise of China, the value of this alliance has increased.

While it should have raised red flags that Abe excited far right elements in the Trump administration, the fact that he is a member of the ultra-nationalist Nippon Kaigi, a growing force in Japanese politics and government since the 1990s, failed to register in the U.S. news media. For the most part, Americans appeared oblivious to what this ideological alignment between the governments of Abe and Trump meant because few were ever given the chance to have a complete understanding of the Pacific War’s ideological terrain and who the Nippon Kaigi are. A 2014 New York Times Opinion piece contributed by Norihiro Kato put their position succinctly: They believe “Japan should be applauded for liberating much of East Asia from Western colonial powers, that the 1946-1948 Tokyo War Crimes tribunals were illegitimate, and that the killings by Imperial Japanese troops during the 1937 ‘Nanjing massacre’ were exaggerated or fabricated.”

Many Americans also seem oblivious to the fact that an undercurrent of anti-Americanism lurks beneath Japan’s new nationalism. The far right position on Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution is as much about throwing off the humiliation of American tutelage as it is a call for Japan to be more assertive in its own security affairs. The fact the Trump-Abe friendship was a slap to the face of liberal democratic elements resisting the militaristic far right has certainly been lost on the majority of the American public. This does not serve the American interest.

The U.S. refusal to understand Japan’s troubling history and its connection to current political trends and controversies is an integral part of our easy acceptance of the simplistic view that Japan is a liberal democratic society and its leaders can do no wrong. For example, it did not seem to matter that Abe’s government – following Trump’s example – weaponized trade in disputes with South Korea over matters of history. It failed to register that this ultimately undermined what has always been a delicate yet necessary bilateral relationship between two of our most important allies in the region. Although Abe is no longer prime minister, his successor has promised policy continuity and far-right elements continue to thrive in mainstream politics. Japan’s relationship with South Korea thus remains fraught. This does not serve the American interest either.

Resting on the assumption that Japan remains a U.S. liberal-democratic protégé, the American news media seldom pays close attention to trends in Japanese politics, no matter how worrying. Much attention is paid to China’s domestic politics, however. High profile human rights violations in Xinjiang and Beijing’s response to unrest in Hong Kong are, amongst numerous other moves by the Chinese leadership to narrow the space for dissent, indeed signals of an authoritarian tightening in Chinese politics. However, these are seldom explained as responses to brewing economic, political, and social problems China now faces, precluding the possibility that leaders are not authoritarian for its own sake. Instead, they are viewed as evidence that China is increasingly menacing in ways that Japan is not.

As far as widely accepted wisdom goes, authoritarian regimes are also belligerent – this frames the American understanding of why conflict is escalating in maritime disputes of the East and South China Seas. Such a worldview precludes the possibility that openly taking sides in these disputes while escalating numerous other fronts of U.S.-China conflict can contribute to China’s threat perception and mobilization. It blinds us to the possibility that China’s leaders fear the ultranationalist leaders of Japan, whom we seem to have no trouble supporting. An unquestioningly pro-Japan stance reinforces the urgency of defending what is seen as a liberal democratic Japan against a communist China, further deepening the anti-China bias.

Indeed, for some time now political rhetoric has been increasingly fanning the flames of conflict with China by framing incompatibilities along ideological and civilizational lines. Folksy nicknames for China and its government such as “ChiComm” do the easy work of combining assertions of what is culturally and ideologically wrong with China, insidiously justifying a new Cold War. Such terms reach into the recesses of U.S. immigration history to summon the specter of images that once again suggest that the Chinese represent a civilization that will corrupt the (white) American nation. As economic-technological competition between China and the United States becomes increasingly securitized, the image of China as “thief” has only strengthened, adding to the moral framing of this anti-China bias. Japan had been accused of technological thievery in the 1980s as well, but not with such persistency.

The problem with drawing conflicts around ideological, civilizational, and moral lines is that it minimizes the acceptability of negotiation and compromise, potentially making this new cold war very hot in the future. Although there is hope that the incoming Biden administration will find more effective ways of conflict management with China, there are already indications that the American public’s imagination of China will limit the extent to which U.S.-China relations can be reset. Joe Biden has indicated that his administration will be ”tough on China,” placing a focus on strengthening its alliances to check China instead of seeking ways to re-engage.

The post-world war geopolitical environment has encouraged the American public to focus on the many beauties of Japanese culture and society while avoiding its troubling history and political developments. Over time, this pro-Japan bias has blinded us to the threat that the far-right leadership in Japan poses to democracy there, and makes it impossible for us to understand how today’s Japan seems threatening to China and our other allies like South Korea, for that matter. We also fail to understand how this pro-Japan bias has long served as a counterpoint to our perception of China, reinforcing threatening images that have more recently been confirmed by the authoritarian turn in Chinese politics. We further fail to understand how this long-held anti-China bias has led to the increasing acceptability of poor conflict management, pushing us toward an unquestioning alliance with Japan that further heightens China’s threat perceptions. It is imperative, however, that we think carefully about how such public perceptions influence U.S. policy choices and behavior so that constructive measures toward stability and shared prosperity in the region can be taken.

Su-Mei Ooi is associate professor of political science at Butler University, Indianapolis. She is the lead author of “Framing China: Discourses of Othering in US News and Political Rhetoric in Global Media and China” (2018).