This is Part II of a three-part series. View Part I here.

Among my happiest recollections of growing up in the eastern Indian state of Odisha was the purnima (full moon) of Kartika in the Hindu calendar (roughly October-November). On that day, our family would awake at dawn, walk to a river, lake, or pond, and launch small boats made of paper, banana tree bark, or lightweight cork material, with lamps or candles perched on top. This is how the people of Odisha (whose ancient name was Kalinga) celebrated the start of the annual voyages of their sadhavas (merchants) in the years past to the faraway lands of Java, Bali, Sumatra, Borneo, Suvarnabhumi (Myanmar and Malaya), and Singhala (Sri Lanka). From the full moon day, there would be a week-long festival and trade fare, called Bali Yatra or the Festival of Bali (Bali in the Odia language means both sand and the Indonesian island of Bali), on the banks of the river Mahanadi in the city of Cuttack. The boat launching ritual and the festival, a joyous celebration of culture, commerce, and companionship attracting hundreds of thousands of people, continues to this day.

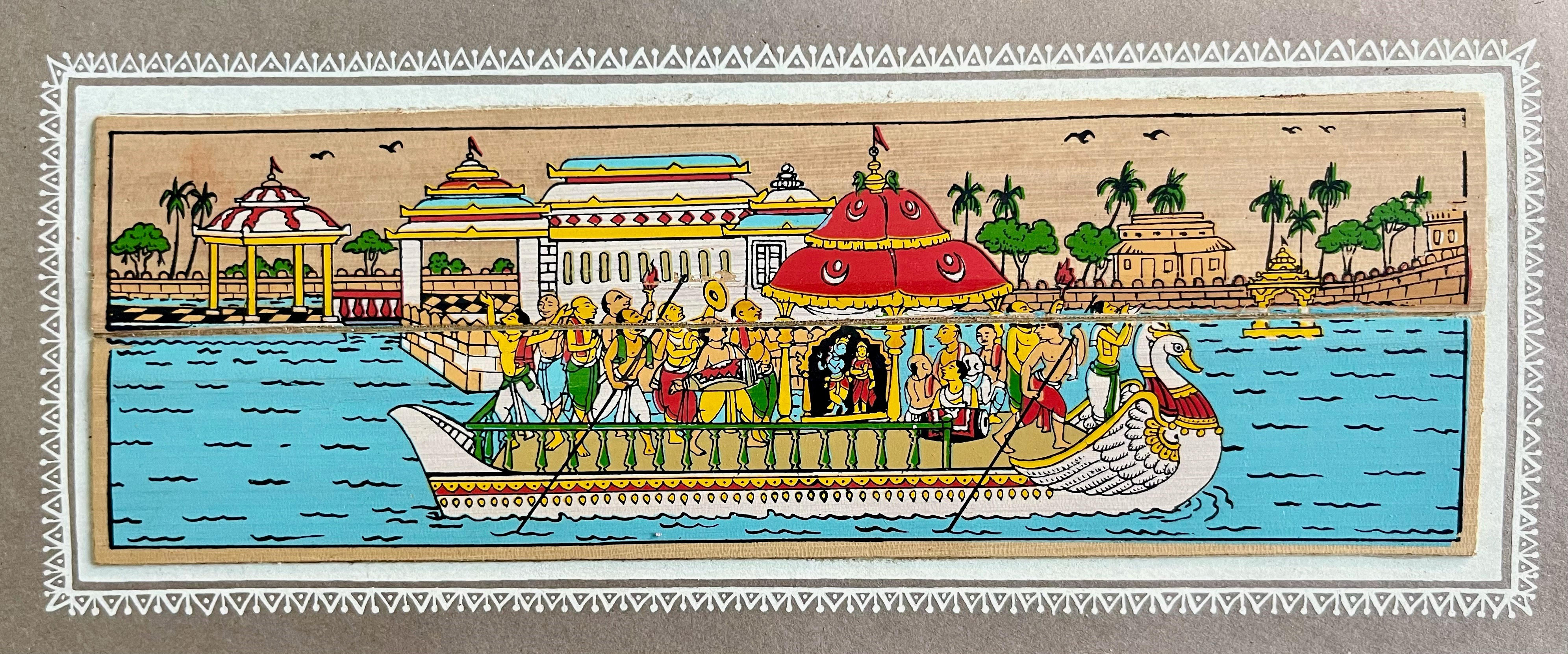

Decades later, when I lived in Southeast Asia for a dozen years, I traveled back in time to compile a poem about making a fictional voyage with the sadhavas (the merchants of Kalinga), to the east around the 15th century. I say “compile” because the poem drew heavily on the social memories of these voyages still found in elder’s tales, folk literature, and traditional silk or palm-leaf paintings (like the one below).

Here is an excerpt from my song of the voyages to the east (note that a padua is a traditional ocean-going boat from Kalinga/Odisha):

A Golden Voyage

The winds, strong and relentless

Brushing our bodies, and stoking our anxious souls

Sails fluttering above the breaking waves

Stroking the salt-baked padua’s hulls

Across the Andaman Sea, our ship laden with pearls and cotton

The faint smell of sandalwood swirling around the cabin

The boat leans left to right and lurches forward

Carrying merchants and dreamers to a golden land

We think of loved ones left behind

Who shall not see us till the monsoon’s end

Yet ahead lies magical places

Sumatra, Java, Bali, Borneo, Malacca and the spice islands

Approaching the Sumatran coast

We stop for a few days of rest

Strolling through the bazaars of Pasai

Dreading the pirate boats that will soon come into view

Moving through the Malacca Straits

Slow but steady in the crowded shipping lanes

Past the anchorage of Admiral Zheng He’s fleet

We step onto the land where the winds from the east and the west meet

Malacca is richer than Venice, the heart of the Malay world

A city that never sleeps, where fortunes are waiting to be made

Bustling with vessels from Palembang, Champa, Martaban, and Ligor

Alongside Chinese junks and the spice-laden boats from Makassar

We deal with the Gujratis, Arabs and Parsees

The merchants of Benton, Tumasik and the Ryukyus

Trading India’s cotton, ivory and pearls

For China’s silk, porcelain and brocades

Business over, we set sail for Java, famed for the majestic Borobudur

Then further to Bali, to watch Barong’s dance, and climb the volcano Batur

Beckoned by gamelan’s enchanting sounds

We pray at Pura Besakih, bustling with Balinese maidens

Months will pass by, as we wait for the winds

To bring back the dark clouds

That will shadow us back to the Kalinga coast

With memories of the golden voyage never to be lost.

A contemporary palm leaf sketch from Odisha (ancient Kalinga), India, reminder of its rich maritime tradition. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

Southeast Asia is the maritime crossroads of the Nirvana Route. It is the place where the civilizations of India and China meet. To some degree, India and China were to Southeast Asia what Greece and Rome were to the Mediterranean, with India resembling the Greek process of Hellenization (indeed, the term “Indianization” has been used to describe Indian influence). China exercised a certain amount of geopolitical influence over the region, although in contrast to the Roman empire, it seldom built an outright empire, with the notable exception of northern Vietnam in the first millennium A.D. The imprint of both India and China was cultural, economic, and political, achieved through commerce more than conquest, through local emulation more than outside imposition.

While Indian influence in China was mostly Buddhist, in Southeast Asia, it was also Hindu, but more often a complex combination of Hindu and Buddhist. Both religions were fused together to shape states and societies in early Southeast Asia. Today, Buddhism remains the religion of the majority in Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia, but even in these countries, the underlying influence of Hinduism remains visible.

How and why Indian religion and culture traveled to Southeast Asia is a matter of debate. There are three theories: Vaishya, Kshatriya, and Brahmana. The first holds that Indian culture was brought by traders to support their economic interests; the second sees warriors and adventurers seeking glory and kingdoms as the principal actors; while the third focuses on proselytization by Indian priests.

It is possible that all the theories have some validity although there is little evidence for Indian warriors colonizing Southeast Asia with force in the manner of modern Europeans. The only major instance of an Indian military expedition to Southeast Asia was undertaken by the Chola kingdom of South India against Srivijaya in A.D. 1025. More likely, Indian culture was called upon by Southeast Asians to meet their own political and religious needs.

Angkor Wat at sunrise. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

The Cosmic Order of Mandalas

How did this happen? The attraction of Hinduism and Buddhism in Southeast Asia was as much political as spiritual. While Buddhism had a political role in China in giving legitimacy to rulers, this was much more the case in Southeast Asia. China had its own ancient political philosophy of Confucianism, which its rulers could use to consolidate their authority. Such an ideology was missing in Southeast Asia, even though Southeast Asians had developed their own civilization to a high standard. Unlike the centralized Confucian state in China, Southeast Asian states were chiefdoms with temporary rulers and uncertain lines of succession.

The arrival of Hinduism and Buddhism brought an elaborate system of beliefs and rituals with which Southeast Asian rulers could claim divine legitimacy before their subjects, for example by identifying with Vishnu, Shiva, or Buddha, and build larger, more organized polities or even empires. Not surprisingly, both quickly became official religions throughout Southeast Asia, with Sanskrit often serving as the principal court language.

The two religions grafted a more organized and durable political order onto Southeast Asia’s loose pre-existing political fabric, although some elements of the latter persisted. This turned Southeast Asia into a region of what scholars would call mandalas. A mandala (circle) implies neither chaos nor absolutism, but a state with loose political organization, relatively mild coercion, fluid boundaries, and overlapping spheres of political authority with neighboring mandalas.

At the same time, mandala did not mean rejecting empire. While Hinduism and Buddhism came to Southeast Asia in peaceful ways, once they arrived, they fed aspirations for universal kingship among Southeast Asian rulers. This meant emulating King Ashoka of India’s Maurya dynasty, who was regarded as a chakravartin, or a universal ruler, and a role model in Southeast Asia.

The arrival of Hinduism and Buddhism deeply influenced the spiritual and political make up of Southeast Asian societies. But it did not displace pre-existing indigenous beliefs and worships. Instead, local traditions and foreign beliefs were fused. To give one example, the “spirit houses” that one finds in every Thai home to this day combine the worship of ancestors and traditional deities with Hindu-Buddhist ones.

Southeast Asians did not merely copy Indian culture and architecture but gave it a distinct local flavor. The largest Hindu and Buddhist temples anywhere in the world are both are in Southeast Asia, in Cambodia (Angkor Wat) and Indonesia (Borobudur), respectively. While they were constructed on the basis of Hindu and Buddhist cosmology, such as the Mount Meru and the stupa (Borobudur combined both), neither is purely Indian in its appearance. They reveal a Southeast Asian “local genius.”

An overview of the Bayon, state temple of Jayavarman VII. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

Imperial Mandalas: Angkor and Bagan

Scholars of Southeast Asia often divide the region into mainland and maritime segments. The mandalas of mainland Southeast Asia combined compassion with conquest. Their rulers were both empire-seeking “world conquerors” and nirvana-seeking “world renouncers,” as the late Harvard scholar Stanley Tambiah put it. Nowhere was this empire-enlightenment link more striking than in Angkor, which grew to be the largest empire of Southeast Asia around the 12th century. During that time, it produced two grand monuments: the Hindu Angkor Wat built by Suryavarman II (1113-1150) and the Buddhist Bayon erected by its greatest ruler, Jayavarman VII (1181-1201).

These and other Khmer monuments provide one of the most striking examples of how art follows politics and how politics shapes art. Angkor’s greatest ruler, Jayavarman VII, embraced Mahayana Buddhism in what had been a staunch Hindu ruling class. The switch might have been inspired by his disillusionment with Hinduism which was seen as having failed to protect Angkor from its sacking by the rival Champa kingdom in A.D. 1177. But after his death Hinduism regained prominence, leading to the mutilation of Buddha images in Bayon, which Jayavarman VII had erected as his state temple.

At Bayon, the face of Avalokiteswara in rain. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

Haunting faces of Avalokiteasvra (Boddhisatva) still adorn the Bayon, which stands at the center of the royal capital of Angkor Thom that was conceived as a Jayagiri, or victory mountain, after Jayavarman VII’s defeat of the Champa kingdom in A.D. 1190. The Bayon contains numerous stone reliefs depicting the battle between the Chams and the Khmers. While Angkor Wat is mainly a religious monument, the Bayon provides an extensive portrayal of society and politics of the Angkor period.

A stone relief at Bayon depicts a battle between Chams and Khmers. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

Ancient centers of Myanmar were another major node of the Nirvana route. A popular Myanmar story about the founding of Myanmar’s most sacred site, the Shwedagon pagoda, attests to this. According to the story, two merchant brothers from Ukkala (modern Yangon), Tapusa and Bhallika, were traveling in India, when they met the newly enlightened Buddha. After offering him honey cakes, the brothers became the Buddha’s first lay disciples. The Buddha gave them eight strands of his hair, which were enshrined at the Shwedagon. According to Pali records, the brothers were actually from Utkala (Odisha) and their link with Yangon was a later formulation. Whatever the case, it was not uncommon for Hindu and Buddhist centers in Southeast Asia to be named after Indian places, the result of close trade, migration and spiritual links. Odisha also inspired the naming of Ussa, the ancient name of Pegu (Bago).

Bagan was where the first imperial mandala of Myanmar flourished between the 9th to 13th centuries. It is still dotted with over 2,000 temples; the original number of temples, small and large, might have been more. These were constructed with tax breaks and land grants provided by rulers such as Anawrahta and Kyansittha, to earn merit for a higher rebirth and ultimately salvation or Nirvana. “The more one donated to the religion – the bigger the temple built, the larger the land and labor endowments one made – the more legitimate the king and his state became. The scale increased as others in the society followed the royal example,” writes Michael Aung-Thwin, one of the foremost historians of Myanmar.

Bagan’s scared landscape. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

Buddhism not only became a source of legitimacy in Myanmar but also a source of rivalry with its neighbors, triggering conflict between the later Myanmar kingdoms of Hanthawaddy (today’s Bago) and Ava and the Thai kingdom of Ayutthaya, including wars over the possession of white elephants, deeply associated with the birth of Buddha.

Murals of Buddha in Bagan’s Chulamani Temple, 12-15th century. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

Maritime Mandalas: Srivijaya and Champa

Srivijaya, centered around Palembang in Sumatra, was at the heart of the maritime Nirvana Route. It was the commercial crossroads of Southeast Asia from the 7th to the 13th centuries, and major center of Buddhist learning. The Chinese monk Yijing, who in 7th century traveled to India to study at the Nalanda monastery and collect Buddhist scripts, spent several years in Srivijaya to translate them and write his own records of Buddhist exchanges between China and India. He described the presence of more than 1,000 Buddhist monks in Srivijaya who could study Buddhism with the same ease and facility as in India. Srivijaya’s territorial footprint and cultural impact extended across the Malacca straits to west Malaysia and southern Thailand, where there are a number of Srivijayan style temples, especially War Phra Mahathat in Nakhon Si Thammarat.

Champa merits its own place in the history of the Nirvana Route. A classic mandala, Champa was a loosely organized polity on the eastern coast of today’s central and south Vietnam. Champa owed its prosperity to its location on the maritime routes that stretched from China to India. Before being defeated by the northern Dai Viet state in 1471, Champa was an enterprising civilization, known for its innovations in architecture, seafaring, and rice cultivation. It was with the help of Champa’s “hundred-day” rice that southern Song China was able to achieve its agriculture revolution to feed millions of its people. Champa rulers claimed personal legitimacy by closely identifying with Hindu god Shiva, although other Hindu deities such as Vishnu and Brahma were also worshiped. In Champa, Shiva was known not as the destroyer of the world (as is the norm in India), but as the protector. At times Buddhism found patronage in Champa, as seen in the relics of the monastery at Dong Duong.

The towered temples of Champa (now called “Cham towers”), combining Indian, Javanese, and Khmer aspects, are not as grandiose as the temple complexes of Angkor. But they are true beauties in brick, representing a high point of artistic achievement in the ancient world. The towers were political-religious shrines, which sometimes served as temple-mausoleums of its rulers.

Champa: Po Klung Garai Temple, Phan Rang, Vietnam. Photo by Amitav Acharya.

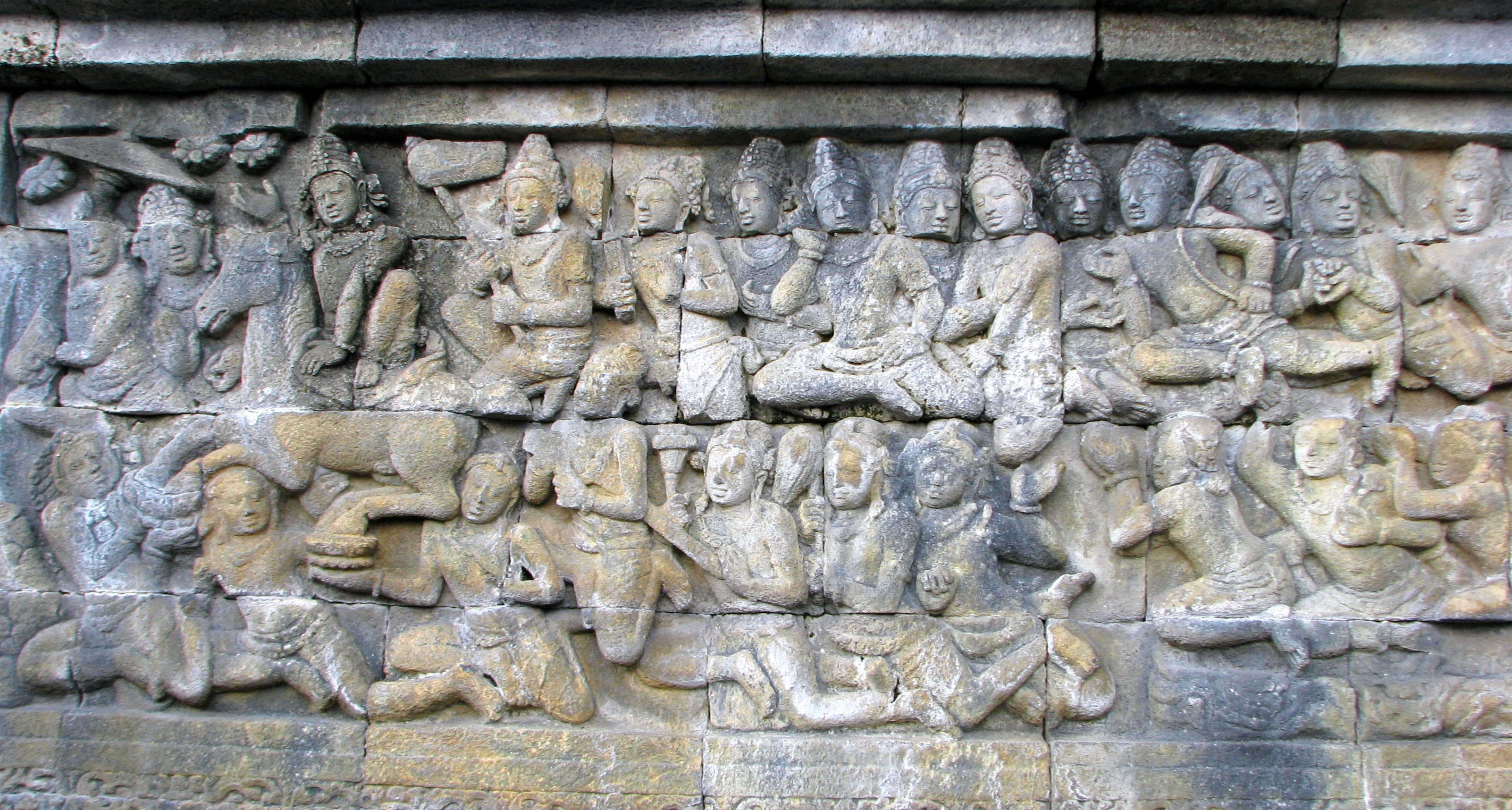

The Universal Mandala: Borobudur

Built in the 8th century by the ruling Shailendra dynasty of central Java, Borobudur is a unique cultural universe combining the features of a mountain, a stupa, and a pyramid of the megalithic period, showing how Indian themes were grafted onto a pre-existing Javanese genius. Its vast reliefs depict two major Buddhist narratives: the Lalitavistara, which narrates the life of Buddha, and Gandavyuha, which portrays the pilgrimage of the youth Sudhana in his search for knowledge. While the life of Buddha is sketched in many Buddhist monuments around Asia, the reliefs of Borobudur contain important variations. One example is the “Great Departure” of Prince Siddhartha from the royal palace as he embarks on his quest for enlightenment. The feet of his horse are lifted by Hindu gods Indra and Brahma to stop any noise that could wake up the guards assigned to prevent his departure; a perfect blending of Buddhist and Hindu narratives of Nirvana.

Relief in Borobudur showing the “Great Departure” (Siddhartha leaving the palace). Photo by Amitav Acharya.

As a Buddhist text, Gandavyuha was circulated widely around Asia, sometimes as a gift among rulers. For example, the Chinese emperor received a Sanskrit language text of the book as a gift from the king of Odisha in the 8th century.

Gandavyuha gives Borobudur a special meaning as a universal mandala. Its message, as leading Borobudur scholar John Miksic notes, is “that one should not expect to find enlightenment only in one place, or in one source. Sudhana’s Good Friends [spiritual instructors] are women, men and children from all levels of society, as well as supernatural beings. Anyone is eligible for enlightenment and there is no suggestion that wisdom is something to be jealously hoarded and imparted only to the elite.”

Borobudur thus represents the essence of the Nirvana Route. Its Buddhist-Hindu conception of enlightenment beckoned all people, irrespective of age, sex, wealth, or place of origin. What a far cry from the European Enlightenment, with its parochial Eurocentric worldview that contributed much to racism, elitism, and imperialism!

Sunrise at the top of Borobudur (with the author on a previous visit to the monument). Photo by Amitav Acharya.