Vietnam has named a senior military officer to head the country’s powerful propaganda department, according to reports in Vietnamese state media, a development that augurs ill for the country’s beleaguered and ever-shrinking circles of dissidents and pro-democracy activists.

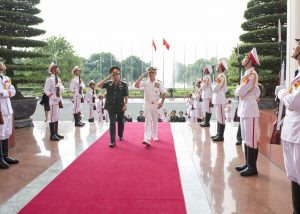

Lt. Gen. Nguyen Trong Nghia was appointed on February 19 as head of what is officially known as the Commission for Propaganda and Education of the Central Committee of the Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP), which is responsible for overseeing the country’s tightly controlled media.

Nghia, 59, formerly served as deputy director of Vietnam People’s Army (VPA)’s General Department of Politics. In that capacity he oversaw the creation in 2017 of Task Force 47, a 10,000-member army cyber unit designed to monitor political comment online, and flood the digital space with content supportive of VCP rule.

The creation of Task Force 47 followed a political report at the VCP’s 12th National Party Congress in January 2016, which highlighted the “radical use of media” on the internet by hostile forces bent on bringing about a “peaceful evolution”aimed at undermining Party rule. At a conference of the Central Propaganda Department in the southern metropolis of Ho Chi Minh City in December 2017, Nghia reportedly told participants of the new task force, “In every hour, minute, and second we must be ready to fight proactively against the wrong views.”

The elevation of Nghia to the head of that department is therefore dire news for the country’s beleaguered community of pro-democracy activists, dispelling any hope of a significant loosening of the political space in Vietnam. Nguyen An Dan, an independent journalist, told Radio Free Asia that the likely effect of the lieutenant general’s appointment would be to squeeze out criticisms of the Party, as well as the sensitive issue of its relationship to China.

“The media in Vietnam will face more challenges and difficulties, and under Nguyen Trong Nghia’s management, Vietnamese media will not be able to post the kinds of stories about China that they did before,” Nguyen An Dan said.

Not that too many observers were expecting Vietnam to take a liberal turn. One of the hallmarks of VCP chief Nguyen Phu Trong’s decade in the country’s top political post is an increasing narrowing of the space for political expression critical of the VCP and its central “guiding” role in Vietnam’s politics.

According to the rights group Human Rights Watch, last year the authorities arbitrarily arrested or prosecuted at least 28 people – among them, bloggers, independent journalists, and villagers protesting land seizures – for violations of elastic national security crimes, such as “conducting propaganda” against the state or “abusing rights to freedom and democracy to infringe upon the interests of the state.” These too place alongside an increasing control over the online space, during with the tech giant Facebook reportedly acceded to a large number of Vietnamese government requests to remove critical posts from its platform.

Nghia’s appointment as propaganda chief also reveals the intertwining of the military within Vietnam’s opaque one-party system. Unlike in nations like Thailand and Myanmar, where the armed forces enjoy a good deal of autonomy from the civilian leadership, the VCP exercises “absolute, direct and all-round leadership” over the VPA through a complex system of party organizations. The Central Military Commission – the highest Party organization in the VPA – for example, is appointed by the Politburo, the Party’s apex decision making body.

According to Alexander Vuving of the Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, a leading observer of Vietnamese politics, the military’s external defense obligations are matched by an equally important internal function:

“Besides the ever-important task of national defense and safeguarding territorial integrity, which no other than the military can fulfill,” he wrote in a recent paper, “there is the central task of protecting the Party, the state, and the socialist regime, which places the military, together with the police, as the armed force of the party-state, squarely at the center of domestic security.”

The politicization of the army – the close interweaving of its role with that of the Party – also makes it among the most conservative elements within a political system that, even as it keeps the VPA firmly under Party control, also serves the interests of the army and its top brass. As Vuving concludes, “Vietnam’s military will likely be the last Leninist bulwark on the country’s road to modernization.”