On the morning of April 24 local time, the Indonesian Navy changed the status of its missing submarine, KRI Nanggala 402, from “sub miss” to “sub sunk.” The announcement dashed hopes of finding the submarine’s 53 crew members alive.

Hours earlier, search assets identified a “high magnetic” force object floating 160-320 feet below sea level as well as an oil spillage near the submarine’s last known location, raising the prospect of finding the vessel. Further investigation and rescue efforts near the area, however, recovered “authentic evidence… believed to be from the submarine,” This included a periscope lubricant, a torpedo protective device, and prayer rugs.

The debris’ identification meant Indonesia would wind down its three-day search for the 44-year-old undersea vessel that lost contact on April 21 during a military exercise, after requesting permission to dive and conduct a torpedo drill. The cause of the sinking remains elusive. Indonesian naval officials suggest an electrical failure prevented the submarine from executing emergency procedures while it sank nearly 2,000 feet or more below sea level.

The accident is worrisome in light of regional developments. The Asia-Pacific’s decade-long arms race, territorial disputes, and access denial campaigns have triggered the procurement and modernization of submarines throughout the region. A greater propensity for undersea warfare, then, must beget a multinational effort to collaborate and enhance submarine safety awareness and protocols as well as search and rescue (SAR) techniques and tools.

For as long as submarines have existed, there have been methods in place to mitigate disasters, saving the lives of hundreds of submariners.

In January 1917, the world’s first submarine rescue occurred. Near Argyll, Scotland, the newly commissioned HMS K13 sank during sea trials. An airline was tied to K13, blowing the ballast tanks, and bringing the vessel’s bows to surface. Rescue personnel cut a hole through the ship, saving 48 sailors.

Tragedies, however, complement and complicate rescue triumphs. On April 10, 1963, the USS Thresher sunk in a trial dive 354 kilometers off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, killing all 129 crew members. The disaster prompted the U.S. Navy to start the Deep Submergence Systems Project. The effort produced the Mystic and Avalon, two advanced deep submergence rescue vehicles (DSRVs).

Despite these advancements, disasters persist. In 2000, a Russian submarine, the Kursk, sunk near the Barents Sea, killing 118 sailors, after a torpedo exploded and detonated the others. Three years later, 70 crew members died on a Chinese submarine during an exercise. Fourteen years after that, in 2017, the Argentine submarine, San Juan, disappeared. The causes varied but solutions to prevent future incidents are not impracticable.

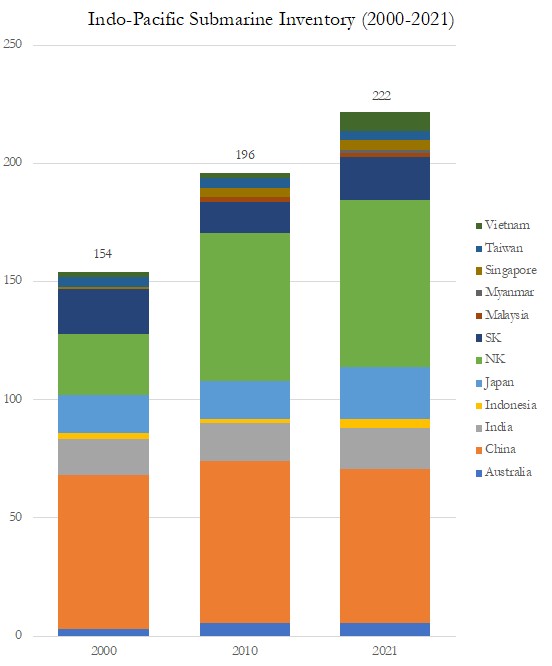

The coming decades will only augment submarine deployments and procurement and, thus, the risk of accidents and sinkings. From 2000 to 2021, submarine inventories in the Indo-Pacific region increased by 31 percent. Those growth rates will continue — if not increase — throughout the 21st century as the Indo-Pacific becomes the heart of “great power competition.”

Chart made by author based on data from the International Institute of Strategic Studies’ 2021 Military Balance.

Beijing seeks to overthrow the United States as the Pacific hegemon. By establishing anti-access/areal denial (A2/AD) zones in the South China Sea, Beijing can diminish Washington’s desire to influence Pacific affairs. To counter this strategy, the United States and its Pacific allies will build and deploy more submarines. Such vessels can access denied areas and provide a strategic advantage through “maneuver, offensive power, and surprise” along with superior firepower and command and control countermeasures.

As Pacific nations build more submarines, SAR success will depend upon multinational cooperation. To help Indonesia locate the missing submarine, the Australian Navy sent two warships, including a sonar-equipped frigate. The U.S. Navy sent a P-8 Poseidon aircraft to locate the submarine and three C-17 aircraft with underwater SAR equipment. Although the KRI Nanggala 402 was lost to sea, the international support made the odds of finding the submarine higher.

Going forward, here are four ways Washington and its Pacific allies can enhance submarine SAR.

First, establish a satellite office of the International Submarine Escape and Rescue Liaison Office (ISMERLO) in the Indo-Pacific. Following the Kursk disaster in 2000, NATO established ISMERLO to coordinate international submarine SAR efforts. The organization consists of a multinational team of subsurface SAR experts that establish international procedures for rescue and offer advice on training and procurements. ISMERLO also has a “rapid call-out” system that rallies SAR resources to recover a missing submarine. Opening a Pacific office, and relocating some experts, could yield frequent, detailed, and longer trainings, procedure briefings, and improved multinational cooperation to prevent submarine accidents or mismanaged rescue efforts.

Second, create an ASEAN Submarine Rescue System. In 2008, the United Kingdom, Norway, and France created the tri-national NATO Submarine Rescue System (SRS) that aims to rescue a crew within 72 hours through its submarine rescue vehicle and portable launch and recovery system. ASEAN nations should work with the three NATO countries (and the United States) to share vehicle and platform technology and establish their own SRS, which would ensure swift emergency response times.

Third, the United States should hold submarine SAR exercises with Pacific partners. In 2017, the United States (with eight other NATO members) conducted Operation Dynamic Monarch, which focused on submarine escape and rescue procedures and training. The United States should host a Pacific-style Dynamic Monarch exercise and invite other non-Pacific partners to observe.

Fourth, the United States Department of Defense should collaborate with Pacific allies by sharing its SRDRS. The unmanned system, which replaced the Mystic and Avalon, can quickly deploy, prepare an area near the drowned submarine, submerge nearly 2,000 feet, and retrieve 155 crew members at a time. Sharing the technology or framework for this system with other nations would allow them to develop their own rescue systems and mitigate future incidents.

The Indonesian submarine’s disappearance and sinking should remind all navies that advanced technology is not a panacea for disasters. With undersea warfare’s intensity growing, it is incumbent upon the United States and other Pacific powers to ensure multinational training, procedures, and cooperation are established to prevent future submariners from losing their lives. As retired British Navy Vice Admiral Clive Johnstone noted back in 2017, “When we are at sea, despite the color of our naval uniform and our cloth, we recognize if you get stuck on the bottom in a submarine that is really frightening. It is every mariners’ responsibility to go to their aid.” No navy or nation should go it alone.