Even though Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi touts the vision of “Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas, Sabka Vishwas” (“everyone together, everyone’s development, everyone’s trust”), India has failed to deliver on its promises. Trade totals with South Asian neighbors remain low, many Indian infrastructure projects in the region are still incomplete, and its neighbors are disappointed with discrimination in aid. China, on the other hand, has extensively made inroads into the region. What are the significant issues hampering India’s economic diplomacy? Furthermore, why has India not been able to resolve its challenges?

Protectionism

One major problem is that India has increased its protectionist approach since Modi’s election in 2014, which has a significant impact on economic diplomacy. The Asian Development Bank, in a December 2020 report looking at 25 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, ranked India 24th on trade openness – only Pakistan scored lower. Despite having implemented economic reforms with liberalization, privatization and globalization (LPG) policies starting in 1991 and signing the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA) agreement for greater economic integration and free trade in 2006, India’s overall trade with South Asia has been low accounting for between 1.7 percent and 3.8 percent of its global trade. India exports in bulk; however, imports are minimal, due to trade barriers.

Integrated Check Posts set up at borders have suffered under cumbersome procedures, like additional checks of trucks and delays in paperwork, that consume both time and profits. The idea behind SAFTA was that neighbors would benefit from India’s economic opportunities by eliminating trade barriers, but this has not been the case. Neighbors have mostly complained about the excessive amount of non-tariff barriers that India has, including clearance procedures, import policy barriers, testing and certification requirements, anti-dumping, countervailing measures and export subsidies, each of which poses an obstacle for liberal trade. Bangladeshi goods, for instance, suffer extensive tariff barriers, hindering free trade, despite the signing of SAFTA.

India is making a deliberate effort to increase its exports to neighboring countries. However, at the same time, New Delhi continues to protect its markets from imports, from its neighbors and elsewhere.

Discrimination in Aid

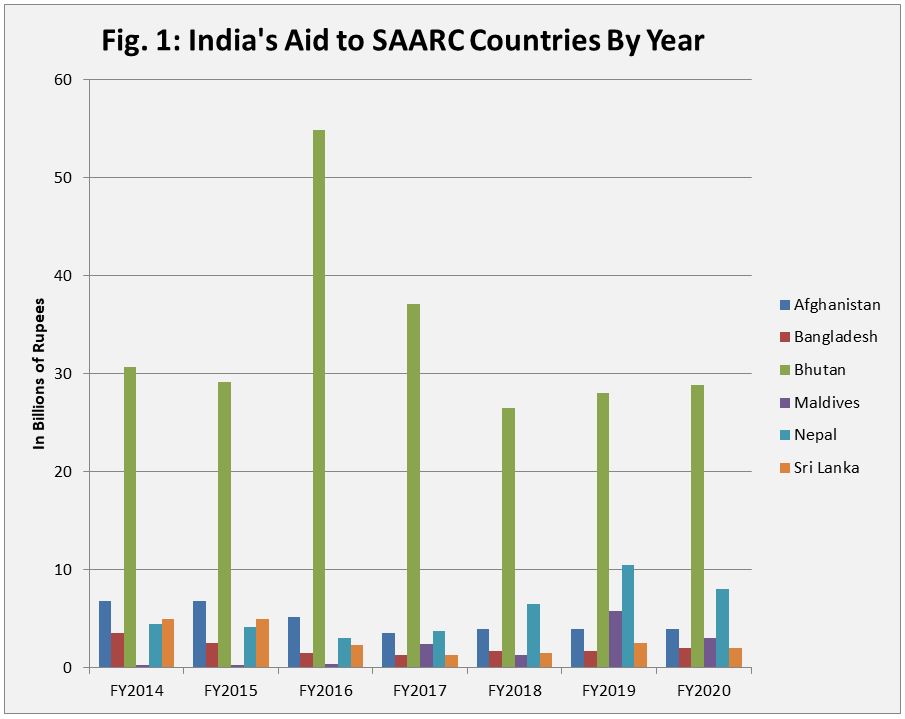

India’s discrimination in providing aid to its neighbors is another issue. India has shown extraordinary generosity toward the Maldives (with whom relations have improved), Nepal, Bhutan, and Afghanistan. In its budgets (shown in Figure 1 above), India provided more aid to these four countries than the rest of the countries of SAARC, leading to insecurity among other neighbors. For instance, in the 2019 budget, Bhutan received 28.1 billion rupees, Nepal got 10.5 billion rupees, the Maldives got 5.8 billion rupees, but Sri Lanka got only 2.5 billion rupees. In the last decade, Bhutan has received 322.8 billion rupees, Afghanistan 48.5 billion rupees, and Sri Lanka only 2.52 billion rupees.

Scholars from Sri Lanka see this as discrimination in aid, feeling India offers more to those strategically more essential. In 2020, amid the pandemic, Sri Lanka requested a moratorium on loan repayments and an additional $1 billion in loans, reportedly from India. However, India did not respond, giving Sri Lanka no option but to turn to China, which offers faster infrastructural development and collaboration.

Nepal has shown similar concerns. India’s budget allocation for aid to Nepal has varied drastically in recent years. Nepal claims that it sees a rise in Indian assistance whenever its relations with China increase, as New Delhi tries to match the contributions that China made. India’s strings-attached aid (highlighting the mercantilist approach of its India-First Policy) has also hindered the healthy growth of economic relations with the people.

A Delivery-Deficit Nation

India’s neighbors have often complained of India making big promises but suffering from a delivery deficit. This is the case with most countries in which India has taken up projects, for instance, road and railway lines, establishing integrated border checkpoints, and hydropower projects. In Nepal, the Police Academy, expected to be complete 32 years ago, is still in limbo. Several more Indian projects are still waiting completion, leading Nepal to turn to China. The case is similar in Bangladesh, where many railway projects have suffered delays. This issue creates negative perceptions of India being lazy and indifferent to its commitments. Some of the projects also lack sufficient funds, which is another issue.

Thus, South Asian countries have no option but to turn to China to reduce their dependency on India. The Chinese have a proven track record of developing infrastructure abroad on time, and give added incentives by making many projects part of the Belt and Road Initiative. China has been busy completing the East-West highway that traverses Nepal and is also working on a railway line from Tibet to Lhasa. It has many projects underway in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Afghanistan as well. China has been increasing its investments in South Asia due to India’s neglect over the years, with Beijing offering a sustained strategy on development projects and the security concerns that emanate from India’s neighbors. This has become a significant challenge for India.

Internal institutional hurdles, such as policy and bureaucratic delays, are another reason why India has been unable to meet its infrastructure targets. Visa restrictions on the movement of people have also hindered regional connectivity and economic engagement in the region. This is a significant disadvantage for India, despite its best efforts to initiate and fund developmental projects. Institutional hurdles pose the most bitter truth: India has still not been able to resolve the challenges mentioned above due to decades of policy stagnation. These problems have dragged down all the efforts that India makes in its own neighborhood, significantly impacting its image.

Conclusion

India’s economic diplomacy has been thoroughly suffering, impacting its image globally and in the region. Reforming its institutional hurdles and laid-back attitude is necessary if India desires to overcome its neighbors’ misperceptions and compete with Chinese investments in South Asia. For this, India must eliminate non-tariff barriers and other trade barriers, strings-attached aid, and complete all the existing projects to regain the neighbors’ trust. At the same time, India must increase its investments and trade with neighboring countries to reap the benefits of greater regional and economic integration, making India open rather than being closed to its neighbors’ economies. Will India rescript its approach incorporate neighbors’ concerns and expectations and improve its economic diplomacy, leading to greater regional integration? The choice lies with New Delhi.